Moon Monday #232: Still free mission updates

And encouraging information sharing.

- In response to the Trump’s administration’s FY2026 presidential budget request for NASA slashing the Artemis projects of the SLS rocket, the Orion spacecraft, and the NASA-led international Gateway orbital habitat after the upcoming crewed Artemis III Moon landing mission, the US Congress passed a supplementary $6.7 billion fund for NASA on July 3 as part of a megabill to continue those projects instead regardless of what the agency’s FY2026 budget proceedings output.

- In what is perhaps emblematic of the inefficiency and mismatched priorities of US politics vis-à-vis its space ambitions, the Congressional megabill also provisions $85 million just to move the ancient Space Shuttle Discovery from the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum to Texas but does not include any funds to reinstate NASA’s VIPER rover mission to study water ice on the Moon’s south pole even though the US has been failing at this goal central to Artemis.

- Last month on June 6, ispace Japan’s second Moon lander RESILIENCE crashed on the Moon due to performance issues with its laser rangefinder. I’ve argued how the outcome underscores the need for resilience in private lunar landing missions through expansive and collaborative testing—something former NASA astronaut and current ispace US Chair Ron Garan has also vouched for. One must note that ispace continued its remarkable transparency from the first failed landing mission, sharing detailed findings of what went wrong in mere weeks.

- The Hawaii-based International Lunar Observatory Association (ILOA) will fly its ILO-1 telescope on the crew-capable FLEX rover by Astrolab (a Moon Monday sponsor). Astrolab leads one of the three competing teams NASA selected last year to mature their designs for a versatile Lunar Terrain Vehicle for use across Artemis missions starting end of decade.

What science will Artemis II do? Zilch?

NASA wrote the following in a recent release on its website about the topic:

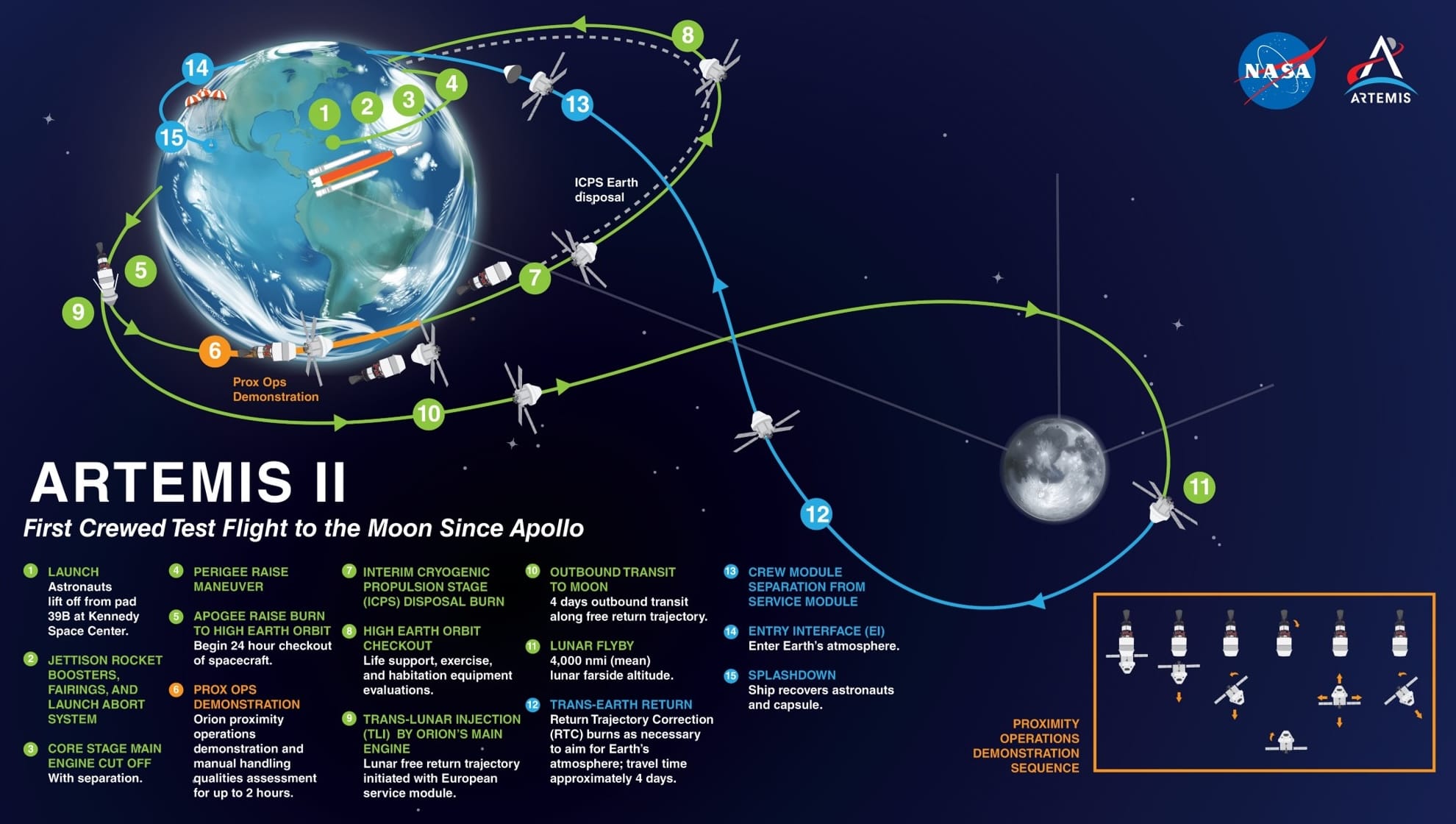

Artemis II astronauts will observe the Moon during their 10-day mission around the Moon and back, taking photographs and verbally recording what they see. Their observations will support science objectives and provide data for potential landing sites for future Moon missions.

Now, Artemis II is not even an orbiter mission. The four-person crew inside Artemis II’s Orion capsule will be flying more than 7000 kilometers from the Moon at their closest approach. What science can they even do from such large distances? And so in less than 10 days? Certainly no landing sites will be selected.

While all Artemis II activities will certainly be useful operationally to feed forward into Artemis III and beyond but doing science as an objective in itself is a different ballgame altogether. Now, every space agency does PR pieces. But NASA used to stand out for clearly articulating the scientific motivations and implementations part of its missions. This webpage release is not one of them.

Related: How NASA has been incrementally planning Artemis III science

Information sharing enables cutting edge lunar exploration

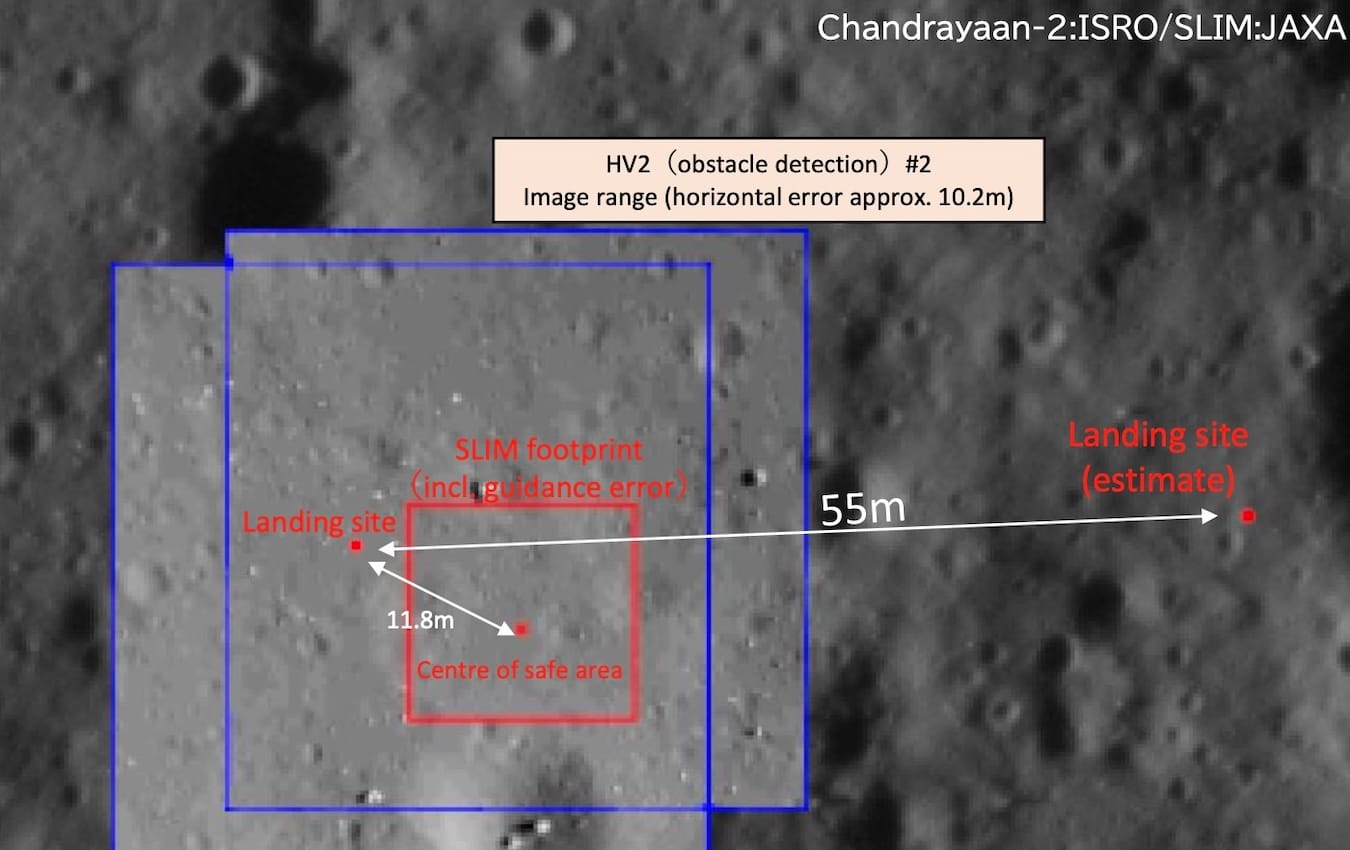

The day was January 19, 2024. JAXA’s SLIM spacecraft just achieved the most precise Moon landing ever for a robotic vehicle, touching down only 55 meters from its targeted point. A unique enabler of that feat was ISRO, who shared its Chandrayaan 2 orbiter datasets with JAXA for landing site selection as well as for SLIM’s onboard navigation maps. Without the world’s sharpest lunar imager, it wouldn’t be possible for SLIM to spot and navigate to a safe touchdown point without compromising the landing accuracy—the primary mission goal. The two agencies are now collaborating on the joint LUPEX rover mission to study water ice on the Moon’s south pole.

It’s a fine example of state actors bridging their unique strengths to gain more than the sum of their parts. There’s also the recent case of international researchers getting access to lunar samples from China’s Chang’e 5 mission for detailed scientific studies. One such lab is from the UK’s Open University. The UK does not have an independent lunar landing program but it does have state-of-the-art laboratories and world-class planetary scientists. With the samples, UK researchers are uniquely advancing humanity’s understanding of our Moon’s origin and evolution, which in itself is tied to that of Earth and the history of our Solar System. For China, it also helps maximize the output of its missions.

Such data sharing and access are useful not just for enabling cutting-edge lunar exploration but to have it continue safely as well. The US, India, and South Korea constantly coordinate their polar orbiters to avoid uncomfortably close passes with each other. A collision otherwise would render low lunar orbit dangerous for all orbiters while also obstructing surface landers traversing through the region.

All of these examples represent commendable efforts from each actor. But unfortunately, they’re also ad hoc or opportunistic in ways that don’t scale with the increasing pace of Moon missions worldwide. Different states share different information at different times, in different formats, and through different channels at varying levels. Information sharing and coordination is thus dispersed, and not efficient for safety, sustainability, or abundant progress. Improving it for more actors can compound perks for all.

To that end, in 2025 the non-profit Lunar Policy Platform (LPP) has embarked on the “Lunar Information Sharing 101” initiative. With funding from the Open Lunar Foundation (a Moon Monday sponsor) and in synergy with UN COPUOS initiatives, LPP spent five months consulting over 70 representatives from 35 governments, space agencies, companies, and experts to understand converging and diverging views on when, where, and how to share lunar mission information. The resulting document will be released publicly later this year after feedback. You can read more about the initiative and contact LPP with your feedback and ideas.

This section was originally published by me on the newsletter of Open Lunar Foundation (a Moon Monday sponsor) as their Science Communications Lead.

There are many ways to contribute to humanity. Mine is to tell people it’s a Monday. 🌝

Many thanks to The Orbital Index and Tim Glotch for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday! If you too appreciate my efforts to bring you this curated community resource for free and without ads, support my independent writing. 🌙

More Moon

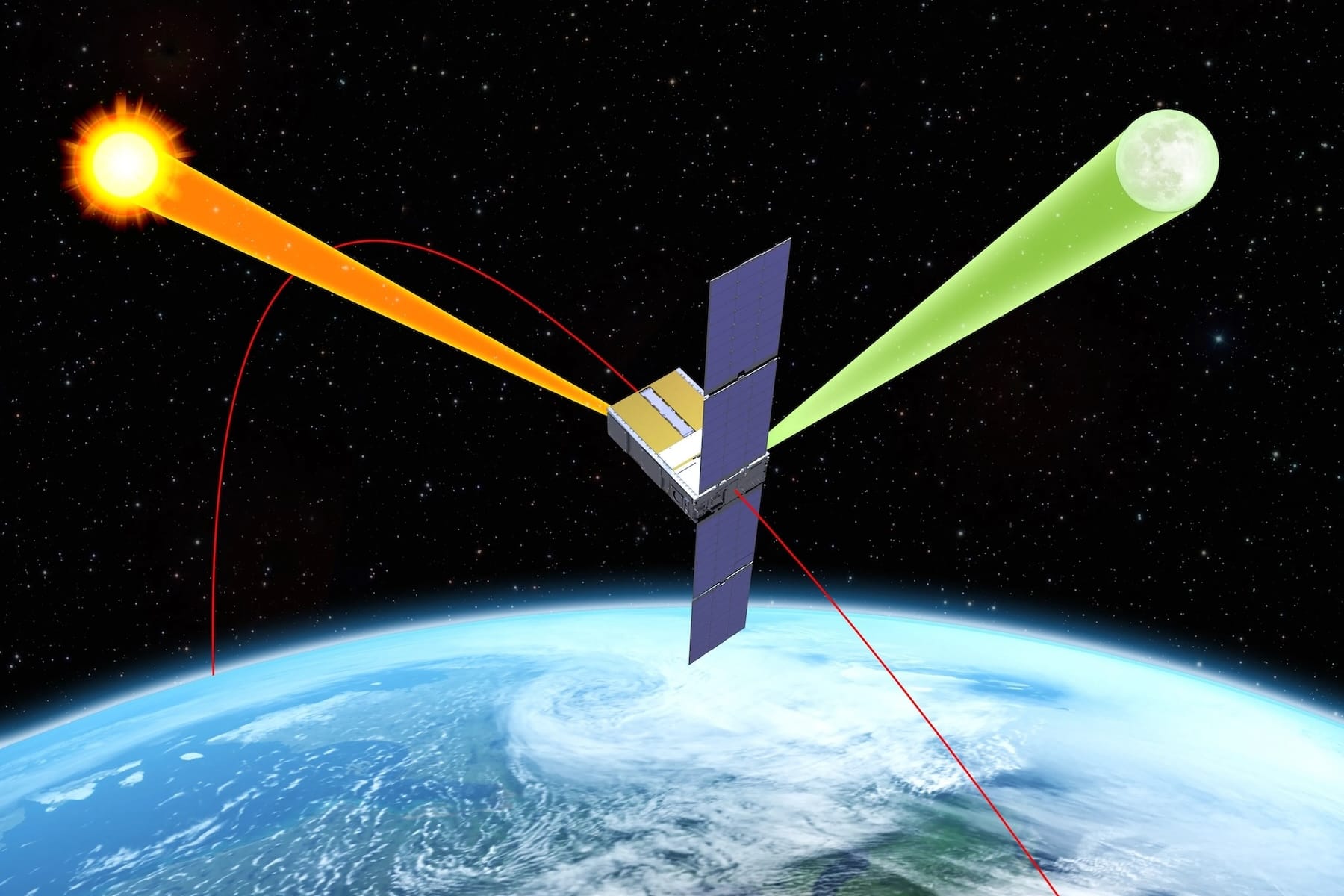

- Earth observation satellites periodically image the Moon to detect, calibrate, and correct deviations in the performance of their imagers. The latter happens naturally due to aging hardware, degradation of imager material or the coating, radiation exposure, and other such factors. It’s our Moon’s stable and known light intensity that allows it to act as an accurate celestial reference for Earthbound remote sensing satellites. And that’s why NASA launched the Arcstone satellite on June 23 to provide state-of-the-art radiometric calibration for Earth Observation satellites. NASA completed commissioning the spacecraft bus on July 3. NASA says Arcstone is “the first mission exclusively dedicated to measuring lunar reflectance from space as a way to calibrate and improve science data collected by Earth-viewing, in-orbit instruments.”

- Another the way our Moon is useful beyond lunar exploration: Repurposing Moon missions to enable deep space exploration

- The Italian Space Agency (ASI) has contracted a OHB-led consortium to develop the flight payload for the ORACLE project aimed at extracting oxygen from lunar soil. ASI has not selected or announced yet which Moon lander ORACLE will fly on but was previously targeting launch by 2028.

- After three collaborative years of research & development and community consultations, the Open Lunar Foundation (a Moon Monday sponsor) has launched the Lunar Ledger (Registry) project in Beta. The ledger of lunar objects and activities hopes to improve operator transparency and public understanding of Moon missions globally. Open Lunar also announced a multi-country Advisory Board for the Ledger.