Our Moon is valuable even beyond itself | Moon Monday #239

And how science does not exist in a (lunar) vacuum.

Very few people know that our serene, silvery cosmic companion’s value lies even beyond the exploration of itself. That’s why I’ve been sharing and writing about various such aspects too and their relevance on my blog and beyond. However, I realized I never brought it all together in one place. Today I’m fixing that. Take a look at these fantastic propositions our Moon offers. Who knows it might be useful during some policy debrief when people want to choose between the Moon and Mars based on logical fallacies tied to mutual exclusions? Our Moon is valuable even beyond itself:

- As a unique platform for radio cosmology to study the Cosmological Dark Ages from the Moon’s farside

- To repurpose Moon missions for enabling deep space exploration

- For leveraging Luna’s unique vantage point to monitor our Sun and its wind

- As a geological time capsule and an age reference for Earth and events across the Solar System

- By studying moonquakes and the lunar interior to understand the origin and evolution of solid surface planets & moons across our Solar System and beyond

- As a well known, nearby reference body to calibrate imagers and radar systems for Earth observation as well as planetary exploration

- For performing some of the most stringent tests of Einstein’s General Theory of Relativity using deployed retroreflectors

- As a good proxy of unprotected solar and radiation in deep space environments to enable future human exploration of our Solar System

- Its regolith being a layered record of our dynamic Sun over the last 2+ billion years, and the interstellar mediums and environments our Solar System passed through in that time

- Enabling an exclusive set of gravitational wave studies of highly energetic cosmic body collisions not possible to conduct from Earth or elsewhere in our Solar System

- As a unique astronomy platform to study magnetospheres associated with exoplanets that are galactically-nearby and potentially habitable

- Perhaps, as a future launch base to other places in our Solar System

Related book recommendation:

There might be a few more aspects that I’m missing and would love to know about it from you! Edit: Many thanks to planetary scientists Ian Crawford and Clive Neal for two suggestions which I’ve incorporated. 🌙

Taken together, the above aspects in themselves constitute a clear rationale not just for exploring our Moon but also standing up for its preservation against pure commercialization and national or private claims of ownership—especially so when it’s the same kinds of exploratory technologies that both enable many of these observations and can eventually destroy them.

Science does not exist in a (lunar) vacuum

NASA’s Apollo missions helped us confirm that our celestial companion had a fiery origin tied to Earth. Soviet Luna missions were the world’s first robotic sample return missions, establishing the modern approach that fetching planetary material to Earth generates scientific results for decades. India’s Chandrayaan 1 orbiter discovered water on the Moon, revealing a dynamic lunar environment and catalyzing global interest in lunar exploration. Japan’s SELENE orbiter extensively mapped the Moon and found openings to long underground lava tubes. Samples fetched by China’s Chang’e 5 mission confirmed that the Moon was volcanically active and thermally complex geologically recently. And Chang’e 6 transformed our understanding of how our Moon evolved thanks to the first ever farside lunar samples.

These are profound discoveries that tie back to the history of Earth and potentially its water. The scientific exploration of our Moon has been a microcosm of what humans globally are cumulatively capable of. And it promises more still as a unique platform for radio cosmology, solar sciences, unraveling the complex history of our Solar System, and more.

But with increasing Moon missions, harsh lunar dust that can go orbital, congestion and lack of regulation in lunar orbit, the lunar south pole becoming a region of convergence and potential contest for technology, mining, infrastructure, and habitat development, and the changing geopolitical environment on Earth, our Moon’s scientific value as an extraordinarily unique time capsule could become increasingly inaccessible and gated.

That’s why the non-profit Lunar Policy Platform (LPP), with support from the Open Lunar Foundation (a Moon Monday sponsor), consulted key scientific organizations like COSPAR and the International Astronomical Union (IAU) as well as universities and research centers worldwide to understand nuances of the situation. In the ensuing guide, LPP finds that because science doesn’t exist in a vacuum, the intersection of national, commercial, technological, and strategic objectives means there’s no single way forward to accommodate the scientific pursuits of all. In the project’s key takeaways shared before the guide’s impending public availability, LPP noted a concluding remark pertinent to preserving lunar science for all:

As lunar development accelerates, it’s tempting to fall back on familiar scripts: that science is neutral, that preservation requires exclusion, and that responsible actors will defer to experts. But the Moon is not just a research site. It’s a commons. [...] We can design governance tools that protect fragile sites without prioritising any one specific activity. Shared-use protocols, adaptive zoning, and rotational access are all terrestrially tested mechanisms that could allow multiple actors to coexist. [...] The challenge is to find that shared margin, ensure that protection does not entrench inequality, and that managed access does not become a proxy for power plays.

This section was originally published by me on the blog & newsletter of Open Lunar Foundation (a Moon Monday sponsor) as their Science Communications Lead.

Key mission updates

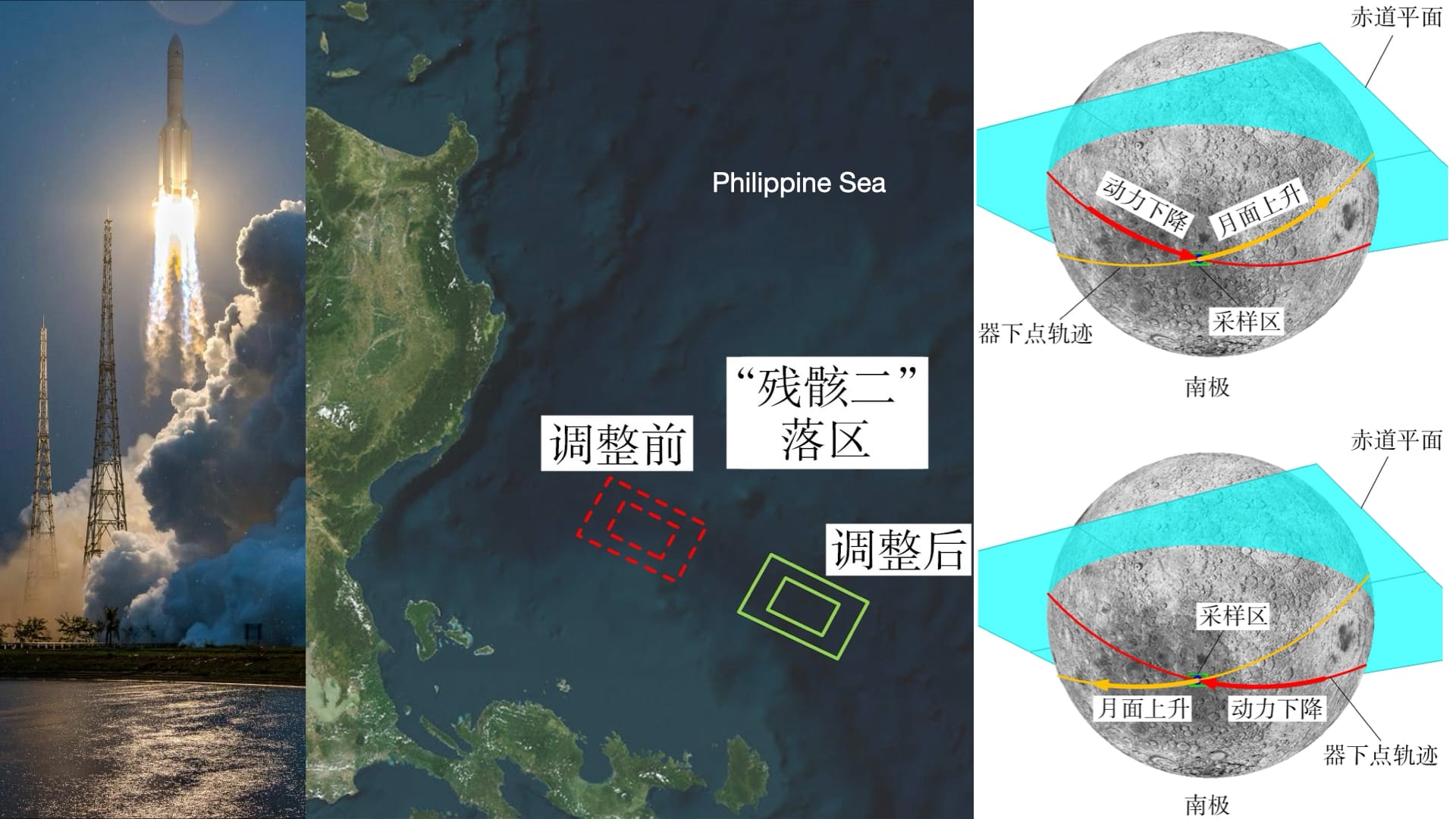

- Ling Xin reports that due to the Philippines government voicing issues against China’s rocket stages entering their sovereign territories at sea, CNSA had to redesign the launch and flight trajectories of the Chang’e 6 mission which successfully fetched samples from the Moon’s farside last year. The report is based on the technical paper published in the Journal of Astronautics by the mission designers themselves, which provides interesting graphs as well. In particular, the mission profile modifications stretched Chang’e 6’s Moonward journey from 23 days to 53 days while narrowing the window for touching down within the primary landing region on the Moon’s farside. The landing region was not to be changed owing to its immense scientific value. At the end, everything has gladly worked out.

- Astrobotic announced that its “LunaGrid-Lite” lunar surface power transfer demonstration mission targeting a 2026 launch has passed the Critical Design Review phase ahead of flight model build and assembly. As part of public-private Tipping Point contracts in 2023, NASA awarded Astrobotic $34.6 million for this mission. After landing, the company’s tethered CubeRover—itself supported by a $5.8 million Tipping Point contract—will unreel about 500 meters of high-voltage, 1 kilowatt power line across the surface. The demonstration will be a test for LunaGrid, wherein Astrobotic aims to commercially deliver power to enable hardware and rovers on the Moon’s poles to survive the poorly lit terrain and frigid nights. Concerning another piece that would be part of LunaGrid, Astrobotic said in May that it has completed the standard but critical set of space environmental tests for its wireless charging system for hardware operating on the Moon. Also related is the company’s development of the also NASA-funded 20-meter tall, retractable polar solar arrays and its newly picked up larger cousin. These are aimed to be deployed on maximally sunlit sites at the Moon’s south pole.

Many thanks to Catalyx Space, Alexandra Witze and Gurbir Singh for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday! If you too appreciate my efforts to bring you this curated community resource on global lunar exploration for free, and without ads, kindly support my independent writing: