When ISRO loses a PSLV rocket, India loses a launchpad in the present and the future

To understand the pride and perils of the PSLV is to understand India’s launch infrastructure and its risky commonalities | Indian Space Progress #35-36

The January 12 launch of India’s PSLV rocket failed due to the third stage’s mysteriously anomalous performance, the resulting tumbling of which was visible even on telemetry screens in the mission control and livestream. 16 spacecraft were lost to the air and sea, spanning a key national hyperspectral satellite, seven private Indian ones, five from Brazil, and one each from the UK, Nepal, and Europe. The European one, called KID, briefly survived and transmitted some information despite experiencing loads up to 30g.

This was the 64th flight of a PSLV, a vehicle which has served India for three decades and is supposed to be the country’s workhorse in space. The flight being PSLV’s second consecutive failure, following the one in May 2025, has invited heightened public criticism and scrutiny, three of which I feel are notable to link and summarize below:

- Mukunth called for transparency in the failure investigation and timely public communications so as to avoid a culture of deviance and complacency, the kind NASA suffered from during the Space Shuttle era.

- Bosky Khanna wrote for The New Indian Express how none of the private Indian company satellites aboard had taken insurance due to cost concerns that exist more so for small satellites than large ones.

- Sidharth MP noted how three national satellite losses over just one year will now cost India several years to replace. This also means India’s dependency on foreign satellite data buys will increase, not decrease.

Now let’s discuss several more key aspects that I haven’t seen talked about so far to understand how it’s non-optional for India to fly the aging PSLV nominally again even as the country expands its launch vehicle options and capabilities—an endeavor in itself throttled. We will also illustrate how the safety of our astronauts on Gaganyaan missions is ultimately linked to the PSLV failure and its misleading communications.

The launchpads of India

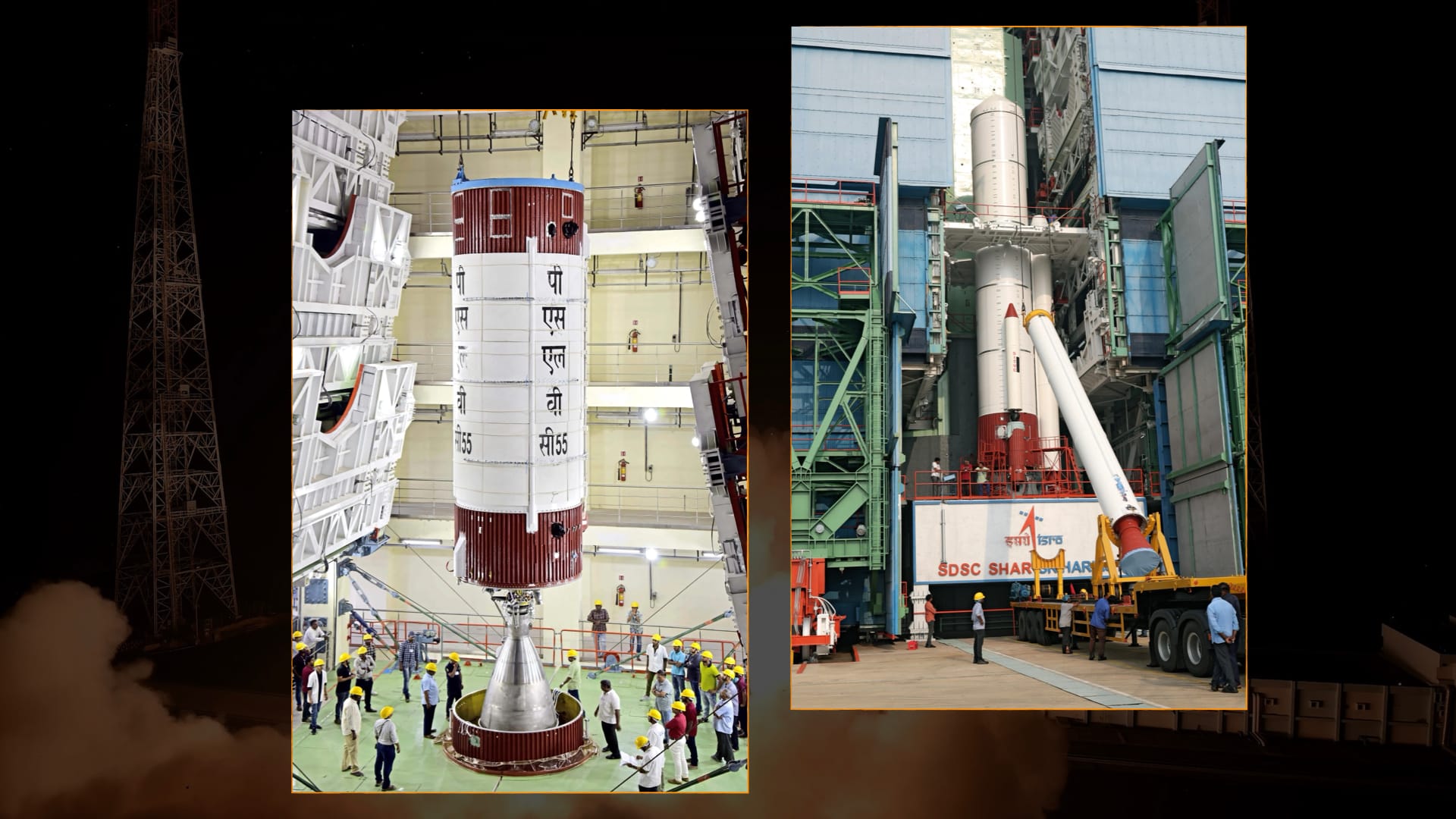

India’s only active orbital spaceport is the Satish Dhawan Space Centre in Sriharikota on the country’s south-eastern coast, a low-latitude location (13.7°N) suitable for many kinds of launches. The port primarily houses two launchpads, and their many associated facilities. The two pads are literally called the First Launch Pad (FLP) and the Second Launch Pad (SLP) respectively. India built the FLP in the early 1990s for ISRO to launch the then-new PSLV rocket. Today, the pad also supports launches of the new SSLV rocket, a PSLV-derived but much smaller vehicle dedicated for lofting small satellites.

As for the SLP, it can also host PSLV launches but does so less frequently as ISRO built that pad in 2005 to primarily launch the heavier rockets GSLV Mk II and LVM3. While these vehicles share some aspects like the liquid Vikas engine with the PSLV, their biggest differentiator lies in their cryogenic upper stages which deliver enhanced performance. However, the same stages make the FLP unable to launch the Mk II or the LVM3. The increased preparatory requirements for these cryogenic stages are hard to retrospectively fit on a launchpad that predates them.

Given these launchpad availability dynamics, it becomes clear that when a PSLV rocket fails, India effectively loses the value of its First Launch Pad. The SSLV exists but is not a sufficiently distinct rocket. Its second stage motor is derived straight from the PSLV’s third stage one—precisely the stage that has now failed twice in a row. As such, the PSLV getting grounded has been pulling down the SSLV along with it. Similarly, the PSLV and the GSLV Mk II share their core stage S139 solid rocket booster.

When the PSLV was flying reliably like a workhorse all these years, ISRO rightly considered the modular reuse from it for the SSLV or other vehicles to be an advantage. Now, however, that has become a restraint. Even when the SSLV gets its own launchpad, planned for later this decade, the issue of potential two-way technological dependency of one vehicle on the other would remain.

No place is building a PSLV replacement

People have expressed hope that upcoming private Indian launch vehicles will resolve India’s launch bottlenecks soon, particularly the PSLV. It’s hard to reconcile this hope with reality. Of all the launch vehicle companies in India, the only one that might launch this year for real is Skyroot. Their rocket, named Vikram-I, though falls in the same category as the SSLV in terms of lift capacity, both lifting six to seven times lower mass than the PSLV for equivalent orbits. In fact, Vikram-I is designed by many ex-ISRO people who were associated with the PSLV or the SSLV, and possibly may be using many common contractors. It’s therefore not a strictly distinct vehicle. Even if Vikram-I is successful in its very first orbital launch attempt, a tall order for any new vehicle, its lift capacity is simply not enough to replace the PSLV. Even its eventual upgrade, Vikram-II, does not come close to the PSLV’s prowess as the latter will still be able to lift about three times more mass to space at once. Another Indian rocket company hoping to launch later this decade, Agnikul, has an even smaller lift capacity to offer than Vikram-I.

There’s also the aspect that the SSLV and Vikram rockets all utilize, or will utilize, the FLP to launch. Even when flying successfully, using the same pad means they will effectively keep blocking PSLV’s FLP launches due to pre-launch planning and post-launch refurbishments while not putting enough mass in orbit by themselves. It’s a tradeoff between the PSLV’s greater lift capacity and the swiftness but low capacity of small rockets.

Now, yes, to improve the SSLV’s own launch rate and lift capacity, ISRO is making a dedicated launchpad optimized for polar orbits. The agency is also aiming to production-ize the SSLV through a technology transfer contract with Indian aerospace industry giant HAL. Skyroot’s Vikram rockets will use this new pad as well. But the fruits of these efforts are not expected to begin until at least 2028, which is when the new launchpad is supposed to host its first orbital launch. And that’s assuming no further delays for the pad that’s already slipped past an originally intended 2025 debut.

If India leans on the SSLV and private Indian rocket companies in their current state for small-to-medium-lift space launches this decade, the country will end up launching far less useful mass to orbit than through PSLVs. There is simply no place in India building a PSLV replacement.

The ambitious transitions ahead

The SLP is the pad India will use to launch its astronauts in the near future using the human-rated variant of the LVM3 rocket. As such, the SLP will further deprioritize PSLV launches to cater to human spaceflight over and above heavier launches. The PSLV will thus increasingly launch from the FLP as years go by. The dedicated PSLV Integration Facility which ISRO built to double the rate of PSLV launches is also at and for the FLP. Moreover, the government’s intent of productionizing the PSLV this decade through the industry also depends on these same existing facilities for the foreseeable future. The PSLV and FLP are two sides of the same coin.

In its early days, the PSLV was a humble rocket that allowed India to place modest satellites in orbit to meet the country’s most basic space applications needs. ISRO then evolved the PSLV with variants to increase and optimize the vehicle’s overall performance and payload capacity. Through continuous refinements, ISRO has been able to use a PSLV in some form to successfully launch a lunar orbiter, a Mars orbiter, a space telescope, a solar observatory to the Earth-Sun L1 point, a record 104 satellites in one flight, and also important missions for other space agencies such as the recent launch of the Proba-3 Sun-studying craft for ESA. This is what people mean when they say India takes pride in the PSLV.

As India’s space ambitions have risen this century, and this decade in particular, the PSLV has reached its ceiling of novelty at last. The next set of complex space missions executed by ISRO involved much heavier launch vehicles to get the job done. To launch Chandrayaan 2 and 3, ISRO required its LVM3 rocket to enter operations. India also needed the LVM3 to loft satellite constellations and heavy commercial craft. A Venus orbiter will also await a ride at the end of the decade. Even more complex missions India has announced to fly soon enough include the Chandrayaan 4 sample return, Gaganyaan human spaceflight missions, the first module of the Bharatiya Anthariksh Station (BAS) astronaut habitat in Earth orbit, and indigenously launched heavy geostationary satellites. But for all of these to work, the LVM3 core stage needs to be upgraded with a semi-cryogenic engine, a project that has been delayed for years now.

In the meanwhile, the Indian Government has approved the building of a third launch pad (TLP) in Sriharikota for $460 million, which will support launches of ISRO’s upcoming heavy-lift NGLV rocket starting next decade. The TLP will also act as a secondary pad for robotic LVM3 launches, and be a standby for human spaceflight ones to handle contingencies and emergencies. The TLP can support launching the GSLV Mk II as well but ISRO is planning to phase out the vehicle itself since the LVM3 is superior to it in performance, price, and reliability beyond bespoke launches.

It’s important to note that just like how the LVM3 and Mk II can’t launch from the FLP, the upcoming NGLV rocket won’t be able to lift off from the SLP. From a technical standpoint, this is obvious. But it’s interesting that the same dynamic that ties the PSLV with the FLP also ties the LVM3 and SLP. This means India cannot afford to lose an LVM3 even more so than a PSLV. And that’s why ISRO’s culture and communications being authentic matter even more today than it did in the past.

Our astronauts on the line

While India can manage a PSLV failure or two, the LVM3 failing would be far more disastrous. The PSLV and LVM3 do share the liquid Vikas engine for the foreseeable future, visibly tying technological reliability of one vehicle to the other. Thankfully, the LVM3 has never failed in its eight orbital flights so far. But then so didn’t the PSLV for 18 years, or a SpaceX Falcon 9 for almost a decade, NASA’s Space Shuttle until its 25th flight, and so on and so forth. We are talking about rockets after all. With LVM3 selected to launch astronauts in the near future, we simply cannot afford it to fail. It’s important to look at any aspect that we can inspect. This is why it’s prudent to note ISRO’s lack of transparency vis-à-vis the PSLV as a sign of the organization’s culture issues.

In 2022 when the SSLV failed on its inaugural flight, we got some decent details like “Cause of anomaly” and “Recommendations & Correction actions”, as probed and implemented by ISRO with the involvement of the failure analysis committee. But for the PSLV rocket which failed in May 2025, we did not get any such details. And that’s despite the fact that the failure triggered multiple mission delays since the launch vehicle’s modules and component designs are also utilized by other ISRO rockets. Even the second PSLV failure last month has still not prompted the taxpayer-funded space organization to release the failure analysis report of the first one, much less its key findings along with a list of corrective measures ISRO took as with the SSLV failure.

You typically expect companies, not tax-funded organizations, to be reserved and even deflective when dealing with failures. Yet even among those there have been companies which lead with transparency. ispace Japan faced two out of two failures of its Moon landers in 2023 and 2025 respectively. Yet, despite being a publicly traded company, it showed remarkable transparency by not only immediately accepting the outcomes in plain words but also by sharing detailed findings of what went wrong within weeks. Shouldn’t our taxpayer-funded agencies be at least as transparent as a good faith space company?

What we have instead are not only no details but outright false statements on ISRO’s website. The mission page for the last PSLV mission, which ISRO published before the launch and its failure, states the following [emphasis mine]:

PSLV is the workhorse launch vehicle of ISRO that has completed 63 flights including notable missions like Chandrayaan-1, Mars Orbiter Mission, Aditya-L1 and Astrosat Mission. In 2017, PSLV set a world record by launching 104 satellites in a single mission.

Except that the 63rd flight of 2025 itself failed. And so did three others in the past. It’s deceiving to call all PSLV flights completed. In the aftermath of the two PSLV failures, India’s Union Minister of Science & Technology and Space, Jitendra Singh, said the following as reported by Soumya Pillai for The Print:

The success rate of our launches is still pretty high compared to any other country around the world. We have been riding high on success, and yes, these failures have come as a disappointment, but we are working to rectify them and be back in the game.

The spirit of the statement resonates but to say that the success rate of our rockets is still pretty high compared to any other country is obviously incorrect when you contrast India’s launch statistics with any major rockets from the US, China, Russia, or even Europe. The PSLV’s success rate may be high but it’s not high enough, and certainly not among the best. That India again had a mixed year in space in 2025 continues to show there’s much more work to do.

There’s no doubt that engineers at ISRO take failures seriously internally. But those efforts also need to be communicated by the agency with honest clarity and effectiveness to retain trust. If an LVM3 fails on a robotic mission, what if ISRO’s opaqueness continues despite the lives of our astronauts being linked to essentially the same vehicle? The world lost astronauts on two human spaceflight disasters with the Space Shuttle due to NASA’s cultural complacency. ISRO would be wise to not repeat history.

The PSLV has a unique place in India’s space program and launch complex. It has to return to flight. But it’s not enough to merely fly the rocket again successfully. The PSLV and ISRO itself need to be made more robust, fixing fundamentals issues and mistakes instead of taping over them, just as ISRO methodically achieved Chandrayaan 3’s triumphant touchdown on the Moon after Chandrayaan 2’s landing failure by carefully planning and testing a more robust and realistically redundant spacecraft.

Many thanks to Takshashila Institution, PierSight, Gurbir Singh and Catalyx Space for sponsoring Indian Space Progress. Thanks also to Deepika Jeyakodi, who kindly wishes me to link to the cause of PARI instead.

If you too appreciate my efforts to capture nuanced trajectories of India in space, provided to space communities worldwide for free and without ads, kindly support my independent writing: