A space program can only move as swiftly as its rockets. It’s India’s time to act on that.

Indian Space Progress #33: A review of the state of ISRO’s orbital launch vehicles reveals a bleak picture of ambitious goals sliding to the right—in stark contrast to the incessant chest thumping about efficiency.

Not sponsored: Among his several books, India’s Forgotten Rocket Pioneer is most relevant to this edition of Indian Space Progress. I also encourage you to check his in-depth podcast episodes on Indian space with experts.

ISRO’s Chief, and more importantly simultaneously the Secretary of India’s Department of Space (DOS), recently stated that India will be able to launch 50 orbital rockets every year by 2029. As a number that sounds fantastic and is coming from the country’s topmost space official, media outlets in India and abroad propagated the news. This isn’t the first time official claims have been made on growing India’s national space launch capacity. Previous official claims and targets include almost 30 launches in two years during this decade and one almost a decade ago of lofting a rocket every month. Virtually every media outlet tracking space nationally and internationally covered these claims too, without checking and reporting later on if any of them were actually realized.

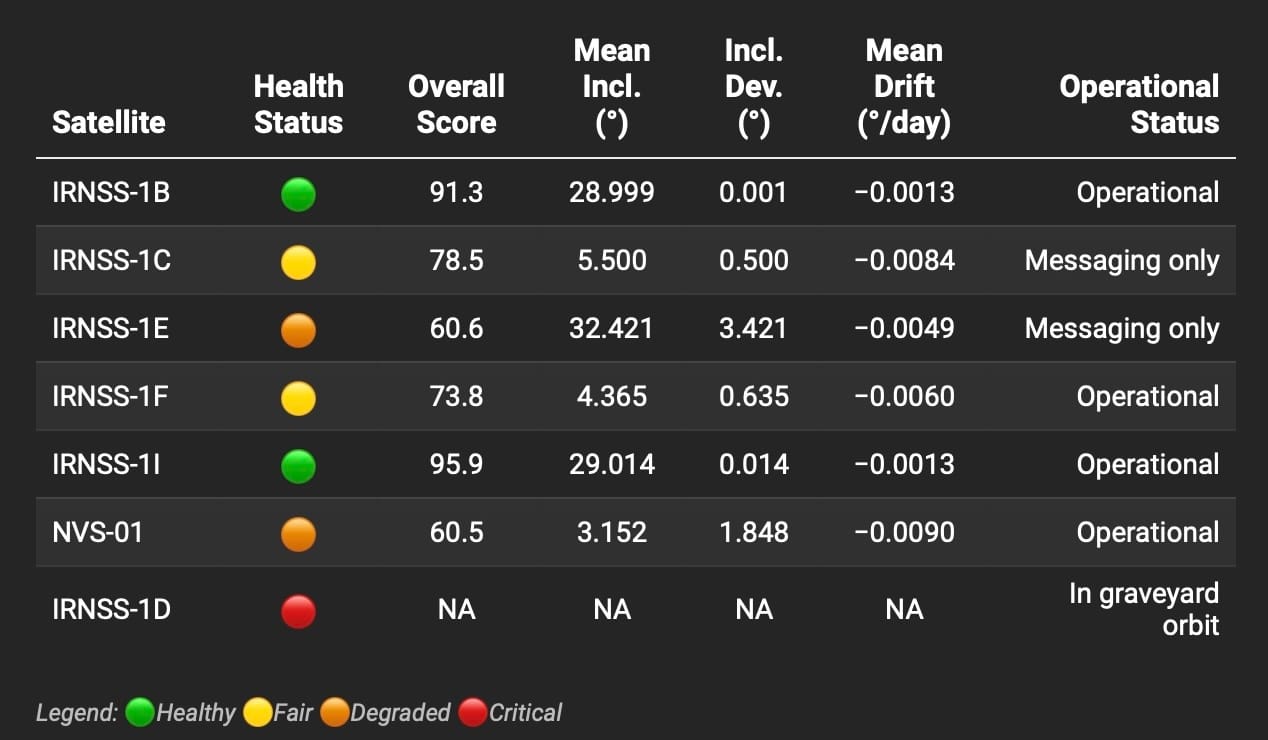

So what’s the maximum number of successful launches ISRO has conducted in a year? Less than 10. Likewise, ISRO’s payload lift capacity has also expanded slower than expected, meaning continued reliance on foreign rockets to launch the nation’s heaviest satellites. It has kinked ISRO’s core mandate of achieving full self sufficiency for the country’s civil as well as strategic missions. The low launch frequency and capacity combined has also affected strategic programs such as the NavIC national satellite navigation system, which has been lingering in an incomplete and underperforming state for years now. The unfortunate failure of the next-generation NVS-02 satellite earlier this year only worsened the situation.

In the meanwhile, recent big ticket successes in other domains of space such as the epitome that was Chandrayaan 3’s landing on the Moon soared India’s civil space ambitions and vision to include the Bharatiya Anthariksh Station (BAS) astronaut habitat in Earth orbit and even humans on the Moon by the end of the next decade. [Translations for non-Indian readers: Bharat = India and Anthariksh = Space in Hindi and several other Indian languages].

How can India grow its space launch capabilities and performance to realize its faster expanding ambitions while ensuring its fundamental needs across civil and strategic space domains are met?

A launch trifecta

To fulfill the nation’s needs and wants in space, three conditions of launch capacity need to be achieved simultaneously:

- Have substantially greater lift mass. The current maximum, by India’s most powerful rocket Launch Vehicle Mark III (LVM3), is only ~8,000 kilograms to Low Earth Orbit (LEO) and barely above 4,000 kilograms to Geostationary Transfer Orbit (GTO). For comparison, the SpaceX Falcon 9 and China’s Long March 5 each have more than double LVM3’s lift performance. Amping up the lift capacities of India’s rockets will allow the country to launch all of its heavy satellites by itself, loft multiple sizable satellites at once, and also execute complex human spaceflight & planetary missions which require heavy spacecraft and modules to be increasingly meaningful.

- Increased launch cadence, the other side of the coin to greater lift capacity. A high launch frequency is a core requirement to sustain crewed space habitats, build and maintain constellations, and—crucially—execute multiple projects in parallel. Having more number of launchpads is necessary to enable high launch frequency, especially to avoid single points of failure or choke points.

- Have dissimilar design redundancy in launch vehicles so that failure of one rocket doesn’t stall launches of others, like the case of the recent PSLV failure due to its modules and component designs also being utilized by other ISRO rockets. Versatile launch vehicles also automatically imply having more and flexible launchpads.

It may be tempting to point to the US and its fleet of medium-lift and heavy-lift rockets as the embodiment of this launch capacity trifecta. But when you consider the last 10 years of global spaceflight, the Falcon 9’s exceptional performance has been an anomaly. More so when you remove the fact that SpaceX’s Starlink satellites are what self-generate high demand for the company’s rockets. Without the Falcon 9 and its relatively sparsely used derivative Falcon Heavy, the rest of the US rocket fleet has not been a spectacle. Certainly not a sustained one. Either way, India simply has neither the sheer funds nor the aerospace industrial strength of America to model the country’s launch capacity on the US rocket portfolio and program management style.

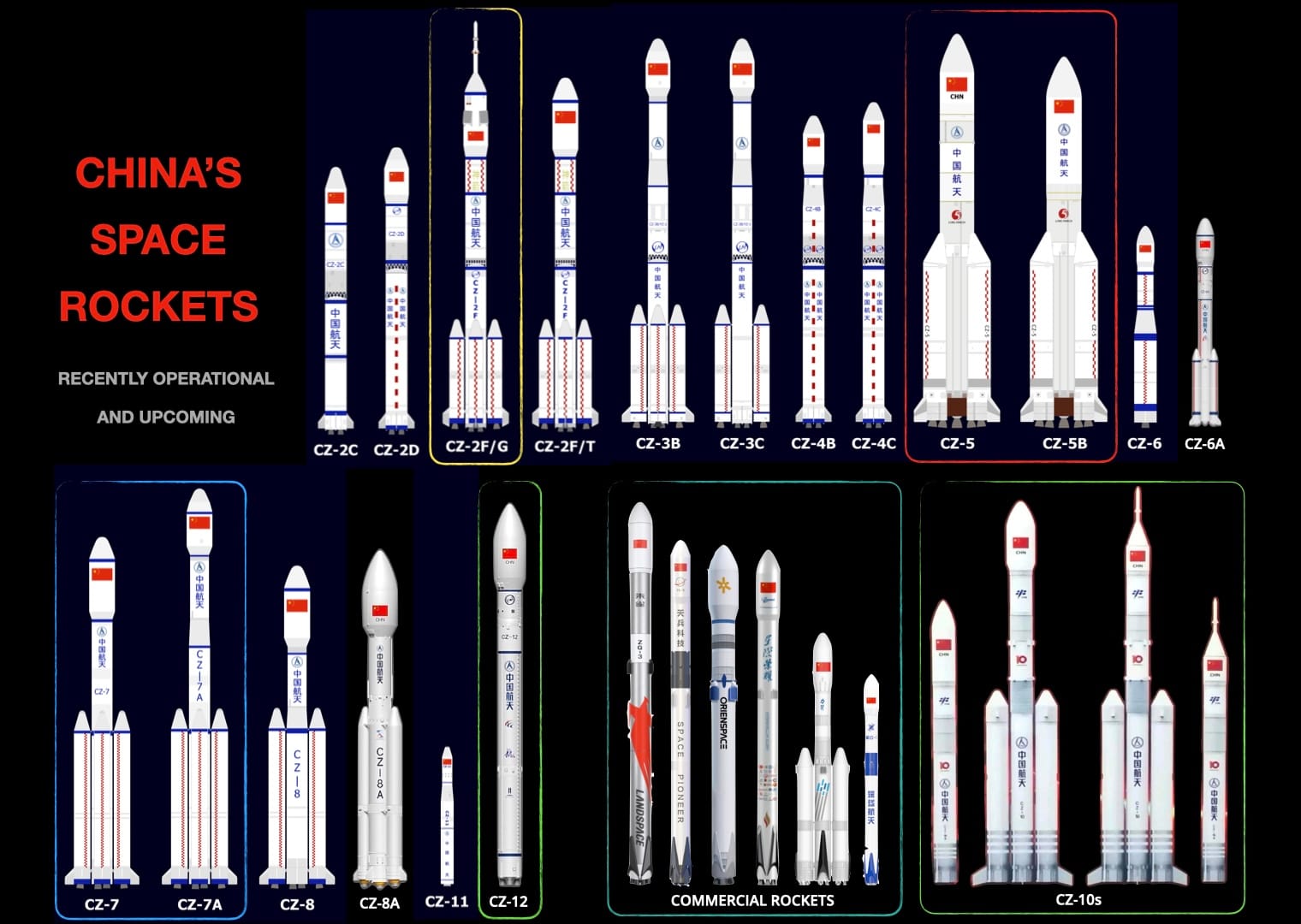

However, China’s multi-faceted approach of prioritizing multi-launcher availability over per-rocket efficiency comes close enough to meeting the three conditions of ideal launch prowess. China’s wide range of national rockets spawned from internal competition and spread across multiple launch sites have allowed it to innovate from Earth orbit to the Moon & beyond in parallel. In the last few years, state-catalyzed operational commercial launchers have also entered the turf, successfully supplementing the country’s launch capacity and frequency. In fact, space launch statistics from 2024 and 2025 show that these non-national Sino orbital rockets alone have launched more times than India could manage across its entire ISRO and private fleet during that period. If we include China’s more frequent & capable national launches of its Long March rockets which support a diversity of national projects, India’s output pales in comparison.

Put another way, China is already doing what India wants and needs: simultaneously maintain strategic space assets, undertake ambitious civil human and planetary exploration missions, and launch commercial & private rockets. Furthermore, just last month China successfully demonstrated an emergency launch to ensure astronaut safety at its space station. It was a grateful verification of working redundancy measures. To reduce the con of cost in its current approach, the country is also on the cusp of achieving reusability within a year with not just one but multiple rocket boosters. Instead of relying on a single flagship rocket like the Falcon 9, China’s resilient orbit access approach is more suitable and desirable for India to draw from.

A shortfall of performance and timing

In October when India indigenously launched its heaviest single satellite yet, it was celebrated as an “efficient” implementation which “tricked” the LVM3 rocket into carrying more weight on its shoulders to GTO than it could otherwise. Of course, the laws of physics haven’t changed. The reality is that said communications satellite, CMS-03, was dropped into a sub-GTO orbit. And so it had to raise its orbit to achieve the desired altitude, a forced maneuver inevitably reducing the satellite’s would-be lifespan.

Had the long-promised upgrade of the LVM3 with a semi-cryogenic core stage engine been realized on time, or even a few years late, it would have unequivocally increased CMS-03’s lifespan. More broadly and importantly, the upgraded vehicle would help India achieve its civil space goals in human spaceflight and lunar exploration faster since both the Chandrayaan 4 lunar sample return mission and India’s first space station module explicitly rely on this yet-to-be-upgraded LVM3 to be available. Now a new report by Sidharth MP claims that India might buy semi-cryogenic engines from Russia for the LVM3 core stage upgrade, suggesting a possible change from the country’s ongoing efforts consistently projected to be achieving “breakthroughs”. However, ISRO is yet to officially comment on this matter. Either way, a semi-cryogenic LVM3 core stage is not sitting on the near-term horizon.

Since 2017, when it first launched as a complete vehicle, LVM3 has lifted off Earth only seven times. Its low production capacity and launch readiness—though acknowledged and stated to be increased—has already led to the delayed launch of Chandrayaan 3 as well as the postponing of India’s upcoming, scientifically important Venus orbiter mission by five years.

A small but important aspect the LVM3 did demonstrate during the CMS-03 mission post-satellite-deployment was to reignite the thrust chamber of the upper stage—but the engine did not restart. This is part of ISRO’s ongoing effort to have multiple engine restarts of the upper stage for future missions. It will be a useful capability for complex orbital deployments of satellites as well as for de-orbiting the rocket stage to ensure space sustainability. But this capability too is coming later than expected, and only gradually so.

Small yet not nimble

Even ISRO’s new SSLV rocket dedicated to launching small satellites has taken more time to be operationalized commercially than projected while its direct global competitors like Rocket Lab and Firefly moved ahead. ISRO through its commercial arm NSIL had said it would launch at least five SSLVs this year. It launched none.

To improve the SSLV’s launch rate and lift capacity, ISRO is making a dedicated launchpad optimized for polar orbits and is also aiming to production-ize the SSLV through a technology transfer contract with Indian aerospace industry giant HAL. But the fruits of these efforts are not expected until at least 2028, which is when the new launchpad is supposed to host its first orbital launch. And that’s assuming no further delays for the pad that’s already slipped past an originally intended 2025 debut. By 2028, the small satellite launch market will also evolve to have fiercer competition.

A similar intent of industry-driven production for ISRO’s workhorse PSLV rocket too hasn’t manifested yet, with the first demonstration flight slipping by at least two years after initially targeting 2024. There has also been no official clarity for years on the realization timeline of the upcoming reusable spaceplane called Pushpak, specifically as to when it will move beyond its current terrestrial subscale landing tests by launching to orbit and subsequently becoming operational. Even though India’s workhorse PSLV rocket failed in May, triggering multiple mission delays since the launch vehicle’s modules and component designs are also utilized by other ISRO rockets, the agency did not share any specific findings of the PSLV’s failure analysis through the remainder year.

Claims by private rockets companies in India like from Skyroot and Agnikul about their orbital launch readiness have sadly been in Elon Musk times. Both companies missed the year 2025 as well for their first orbital launch attempts against their own revised projections. Now, one does need to account for the fact that India’s private orbital launch companies are fighting an uphill battle in a constrained financial environment. These companies are not state-catalyzed technologically either like the Chinese launchers are, thus taking time to gestate. Skyroot finally seems set to attempt its first orbital launch in Q1 2026. Even though maiden orbital launches of new rockets globally have a poor track record, I hope it achieves a successful trajectory.

Even when India’s private companies eventually launch successfully and then hopefully operationalize soon, it’s doubtful if small lift launchers have a sizable market to serve to begin with in order to be revenue positive. Instead of supplementing national capacity in the vein of Sino commercial rockets and turning Indian launches into a good export business, these might end up directly battling against ISRO’s own SSLV rocket for the small number of small launch customers. In the meanwhile, claims about demand and expected profits from these companies have kept soaring but the reality is most of them might not make it in their current forms. It would be better if ISRO instead technologically catalyzed these rocket companies to let them innovate faster and thus expand national launch offerings instead of the companies being left to reinvent wheels that may not even be round.

Many thanks to Takshashila Institution, PierSight, Gurbir Singh and Catalyx Space for sponsoring Indian Space Progress. If you too appreciate my efforts to capture nuanced trajectories of India in space, provided to space communities worldwide for free and without ads, kindly support my independent writing:

The next decade and NGLV

As is evident by the trajectories of India’s rockets in the last 10 years, even though a trickle of efficiencies have come in here and there, the overall launch output has grown far slower than projected, expected, and necessary. Especially when not isolated from the global context. Mukunth captured this well when he said in his own piece on the trajectory of India’s rockets:

The fact is the Indian space programme can take great strides and still remain uncompetitive with the other countries belonging to the same elite club to which it has repeatedly claimed to belong. While the U.S. and Russia (including the erstwhile USSR) had a head start of many decades, China, Japan, and Europe for a long time enjoyed more funding, technological sophistication or both [than India].

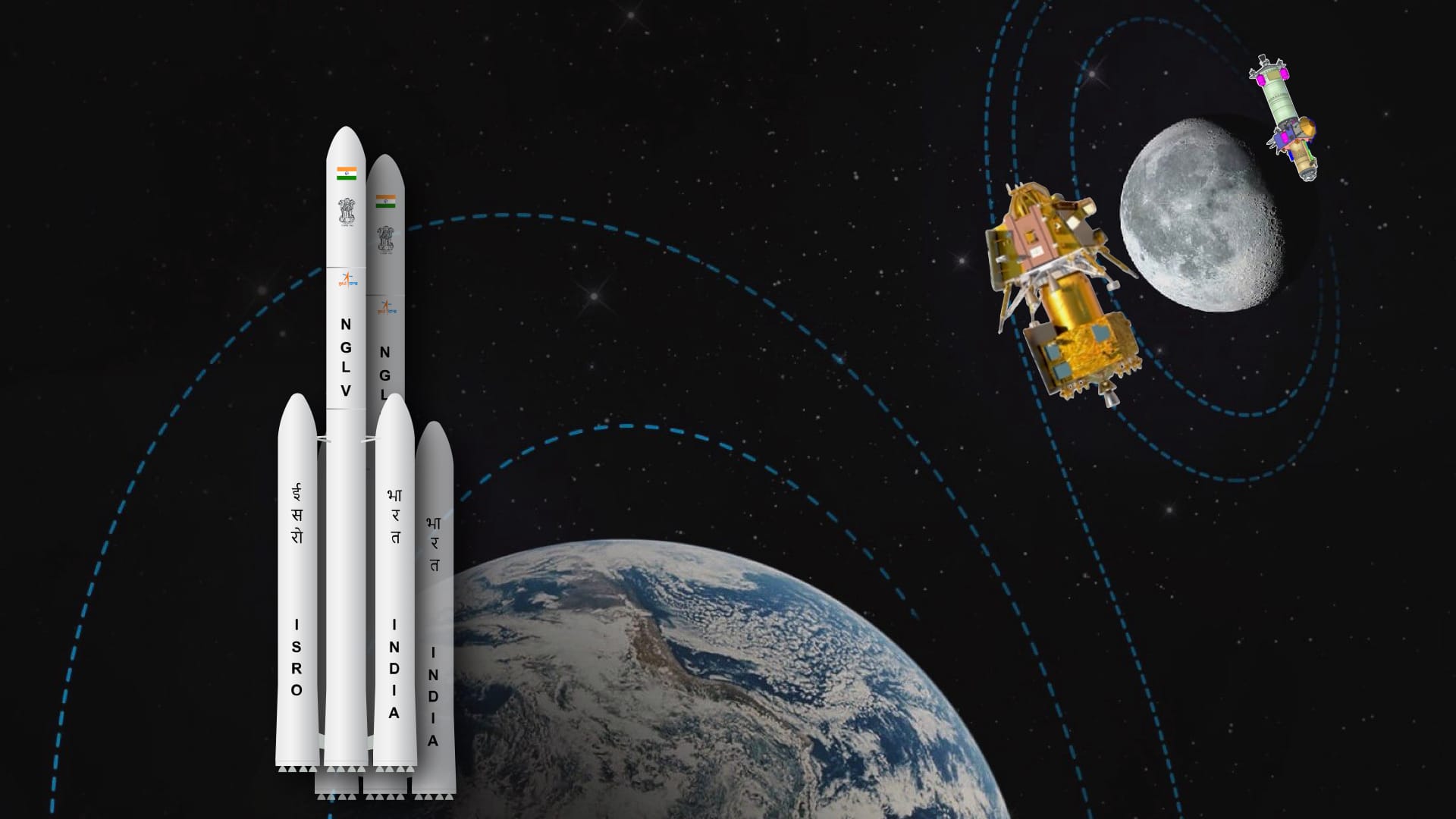

To work towards a change of scale, last year the Indian Government Union Cabinet did approve ISRO’s proposal to develop a partially reusable heavy-lift rocket for $982 million. Called the Next Generation Launch Vehicle (NGLV), the cryogenic rocket will be capable of lofting up to 30,000 kilograms to Low Earth Orbit in expendable mode, and 10,000 to 12,000 kilograms to GTO. That’s about thrice the oomph of the LVM3. The NGLV will also have engine restart capabilities; the booster will leverage that to return to Earth for launch reuse, and the upper stage will relight to perform complex orbital maneuvers and deployments. There are tentative plans for a version of the NGLV with powerful strap-on boosters, called NGLV-H, to further improve lift mass.

The Indian Government has also approved the building of a third launch pad at Sriharikota for $460 million, which will be used for NGLV launches. It will also provide LVM3 with a second launchpad. Combined, the NGLV and the upgraded LVM3 have the potential to approach the ideal trifecta of launch characteristics and thus meet India’s needs and ambitions in space.

However, ISRO is targeting the first half of the next decade to realize the NGLV and make it operational. A major part of it has to do with India’s long-constraining yearly space budget. The NGLV project’s budget allocations are distributed across many years, stretching the realization timeline beyond the fastest viable technical path. In other words, ISRO’s engineering talent will not be utilized efficiently due to fundamental budget constraints that have no viable technological design alternatives. Despite the recent government approvals of multiple ambitious national space projects, India’s space budget for FY 2025-26 essentially remains flat at about $1.5 billion. That’s less than a tenth of the funding enjoyed by both CNSA and NASA respectively.

To the Moon?

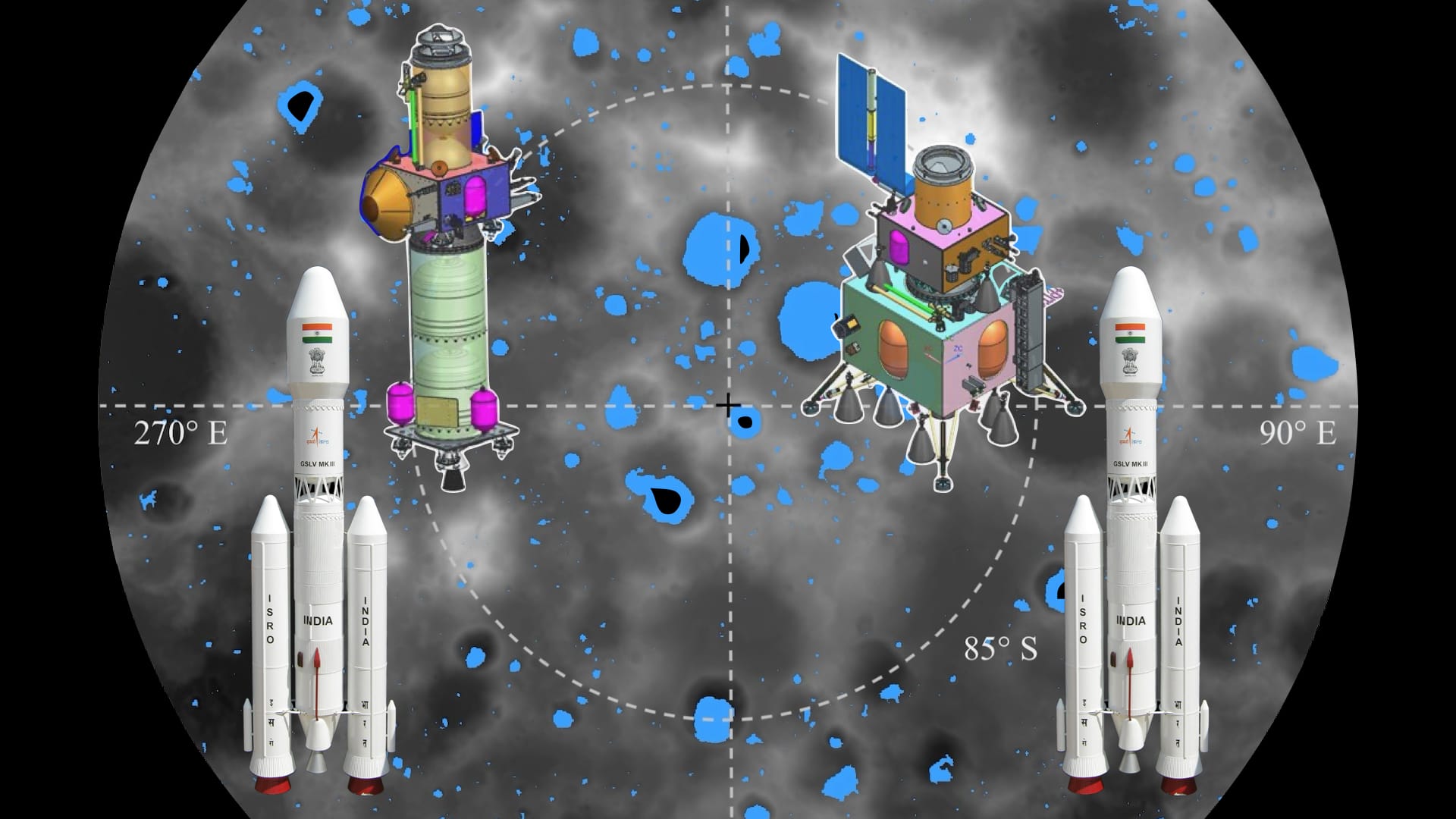

The budgetary reality hasn’t stopped India from becoming the third nation this century to announce the goal of sending humans to the Moon by itself. The official timeframe is 2040. Realizing monetary constraints, ISRO’s Moonshot approach is to explicitly not make an ultra expensive, single purpose Saturn V class mega rocket. Instead, ISRO will utilize docking of multiple spacecraft elements that are launched separately on maxed-out heavy-lift rockets to then achieve the same goal. This is a scaled up version of the docking-based architecture that Chandrayaan 4 will employ to fetch lunar samples later this decade. With this approach, the same rocket that launches humans to the Moon can also serve other projects in India’s space program, saving costs and ensuring efficient use of taxpayer money.

However, getting to repeatedly and reliably launching India’s largest rockets will still cost substantially more money by itself than is available to ISRO. Per the current but morphing plan, Moonbound Indian astronauts will blast off from Earth on a maxed out NGLV rocket variant. As will their lander in another such launch. Developing this central crewed Moon rocket in itself relies on the baseline NGLV launch vehicle coming online and becoming operational faster than its current official projections. Moreover, using a scaled up Chandrayaan 4 architecture implies having reliable back-to-back launches of the largest rocket India will have ever flown. And, redundancy for astronaut safety necessitates ensuring that an alternate launchpad is available for emergency launches and crew-cargo-supplies to Luna instead of just the one pad planned at the moment. The recent Soyuz rocket launch which damaged Russia’s singular launchpad for human spaceflight and associated cargo supplies reinforces the importance of this aspect.

As such, even without a super heavy-lift rocket to blow money onto, the minimum viable cadence and scale of heavy-lift launches necessary for sending crew safely to the Moon and back can neither come for cheap in itself nor can it be achieved with any amount of pure efficiency attained with subpar hardware. Let’s not forget that the small robotic Chandrayaan 3 spacecraft alone filled LVM3’s payload capacity to the brim. For a crewed Moon rocket, a giant leap is an immutable requirement.

Just like India bagged Chandrayaan 3’s triumphant touchdown on the Moon by cutting through the cloud of Chandrayaan 2’s failure with an approach of expansive testing coupled with uncompromising performance, the time is here again to reinforce and scale that philosophy to the largest playground in space this century.

Make no mistake, it will be the pinnacle of India’s space program if it launches humans to the Moon circa 2040. Imagine that future for a moment. The only country in the world after the US and China to achieve the immense feat, and one bagged within 100 years of independence from colonial claws. Had ISRO’s founder Vikram Sarabhai been alive, he’d probably tear up at the sight of this feat. He’d also know that a scalable heavy-lift rocket investment was indispensable so that India could orchestrate the increasingly complex sprawls of its space program.

Like my writing and coverage? Support my work to help sustain independent writing and journalism.