Moon Monday #177: China’s lunar base, the depths of polar water, mission updates, and mountains

Welcome to the fourth Chinese lunar special after Moon Monday #174, #175 and #176. In this edition, the top story focuses on contextualizing all we know about China’s plans to create a long-term Moonbase.

Through a CASC news release on April 26, chief designer of China's lunar exploration program Wu Weiren revealed that the upcoming Sino-led long-term Moonbase called the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS) will have an orbital presence too. While this element of the otherwise surface-based ILRS located on the Moon’s south pole will only exist circa 2045, the news page says the space station will be of “considerable scale” and host multiple continuous experiments. CNSA’s Queqiao satellite constellation should be fully online by then to serve the navigation and communications needs of the many orbital and surface lunar assets operated by China and its currently about two dozen partners. China aims to have 50 nation partners and 500 international organizational collaborators for ILRS.

Following China’s first crewed Moon landing, currently targeting 2030, the country will focus on building the surface phase of ILRS circa 2035. Key to realizing this is a new super heavy-lift—and eventually reusable—Saturn-V class rocket called the Long March 9. China announced in April that it aims to test launch a Long March 9 by 2032. The rocket can put 50,000 kilograms of spacecraft hardware on a Moon-ward trajectory, which is almost twice the performance of the Long March 10 and NASA’s current SLS rocket both of which will be used to send humans to Luna. Relatedly, Andrew Jones reported in May 2023 that China started using an advanced new facility in Tongchuan dedicated to test firing huge rocket engines, starting with the ones being prototyped and built for the Long March 9 and 10.

Once the Long March 9 is operational, China intends to use it to deliver huge amounts of cargo, and possibly even more crew, to the ILRS Moonbase. The rocket will deliver critical infrastructure for sustainable surface hubs via missions named ILRS-1 through 5. This includes infrastructure for energy needs, communications, transportation services (including landers, rover, hoppers, and ascent vehicles), scientific research equipment, in-situ resource utilization technologies, and more.

The ILRS Moonbase will host large-scale science and technology experiments continually via remotely operated robots and, when available, via humans. It was in 2023 that China finalized key scientific goals of ILRS, as stated by Zou Yongliao, head of the lunar and deep space exploration division at the Chinese Academy of Sciences. These goals are:

- Learning about our Moon’s evolution & structure

- Conducting lunar-based astronomy for doing cosmology and studying habitable exoplanets

- Observing the Sun and Earth from the scientifically unique vantage point of our Moon

- Conducting lunar-based experiments like studying plant growth

Building on Chang’e 8 and China’s first crewed landing, ILRS will also see multiple demonstrations related to extracting and using local lunar resources such as water ice, and melting soil to create 3D-printed structures.

Relatedly, a recent document China submitted to the UN COPUOS concerning the legality of utilizing lunar resources suggests that the country sees such activities as permissible under current international law in much the same way the US-led Artemis Accords does. Some western experts saw China’s action as a positive development since it can now enable—in principle—a mutual dialogue for cooperative resource governance amid a decidedly international fora. In the Explainer Series by Spaceport SARABHAI, Professor Yun Zhao provides high-level context on China’s legal space landscape and the lens through which the country might view such activities.

The search for lunar water deepens

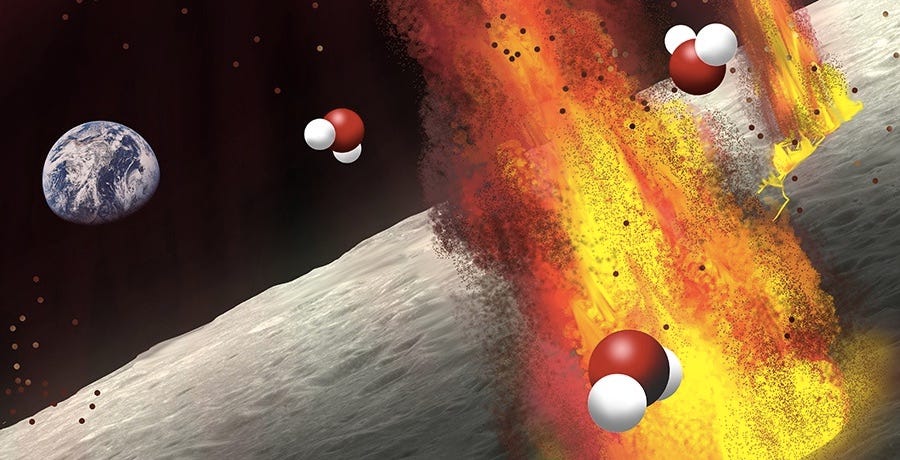

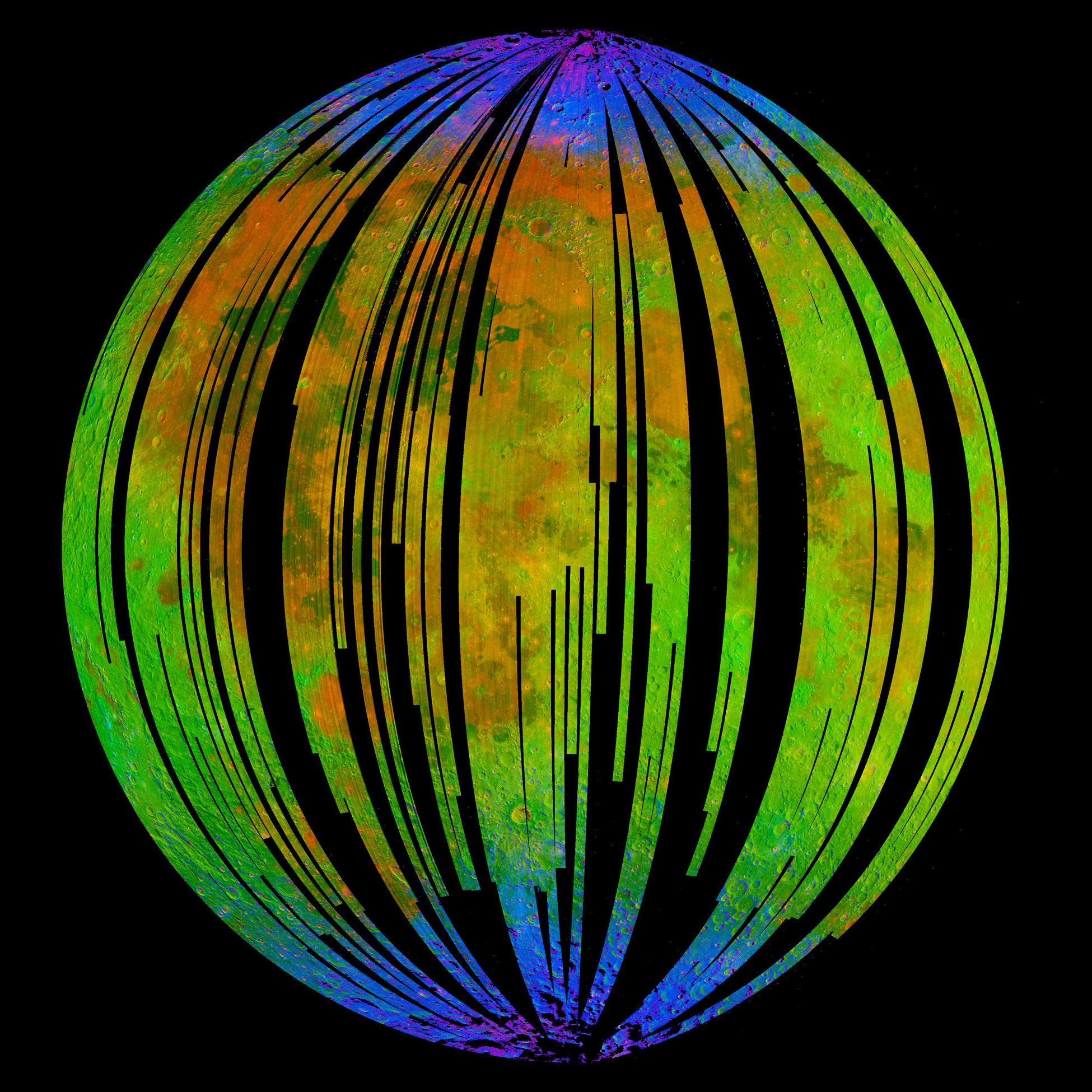

By combining optical, radar, neutron, and other data from NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO), complemented by the ISRO Chandrayaan 2 orbiter’s dual-frequency SAR observations, a new study led by several Indian scientists estimates that the Moon’s poles host five to eight times more water ice 1-3 meters underground than near the surface. They also find that the extent of such water ice appears to be about twice as large at the lunar north than south.

The study has implications for the many upcoming lunar missions dedicated to studying the nature, abundance, and accessibility of lunar water, which include CNSA’s upcoming Chang’e 7 mission, the NASA VIPER and JAXA-ISRO LUPEX rovers, and NASA’s Lunar Trailblazer orbiter. [Tangent: ISRO aids Artemis]

The study also suggests based on various factors that the Moon’s past volcanism is the primary source of this subsurface water ice. And indeed, a May 2o22 paper aggregating and analyzing results from multiple orbiters and studies has also posited volcanism to be a viable source of lunar polar water deposits. But not all researchers agree.

A February 2022 study analyzed water and other volatiles detected by NASA’s LCROSS spacecraft to determine the likelihood of their source being volcanoes, comets, micrometeorites, the solar wind, or even the Earth’s atmosphere. The volatile ratios from the study suggested comets to be the most abundant lunar water source followed by micrometeorites. A related 2020 study supports this view too since it found that even temporary atmospheres created by the peak volcanic Moon over 3 billion years ago were likely inefficient in transferring and depositing lots of volatiles to permanently shadowed regions on the Moon’s poles.

Scientists figuring out this and other related Moon mysteries will help us know not just how our Moon evolved but also what kinds of processes drive the evolution of airless planetary bodies across the Solar System.

Many thanks to Open Lunar Foundation, Off Planet Research and The Orbital Index for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday! If you love this curated community resource too, join them and support my work.

More mission updates

- Philip Sloss reports that the launch of the first two modules forming the NASA-led Gateway lunar orbital habitat could now be as late as December 2027 instead of September 2025. The Gateway’s HALO habitat module is undergoing a series of structural stress tests after which its components and subsystems can be outfitted later this year. For its SpaceX Falcon Heavy launch, HALO will be docked to the PPE propulsion module pre-launch. The PPE structure is now ready for installation of its propulsion system components, starting with tanks. NASA will conduct the critical design review for the integrated spacecraft in the second half of 2024.

- Also see: A gist of Gateway science

- For a future Moon landing mission currently targeting a 2027 launch, ispace is exploring the feasibility of using radioactive heater units (RHUs) from the University of Leicester to enable the lander to survive frigid lunar nights. The university is doing said technology development in collaboration with the UK’s National Nuclear Laboratory, with funding and support from ESA, UKSA, and the UK International Bilateral Fund. Recall that ispace Japan was awarded a $80 million government grant in October 2023 to develop and launch this lander, whose design is called Series 3. It will carry more than 100 kilograms of payload to the Moon as opposed to the 30-kilogram capacity of Series 1, which flew on the company’s Mission 1 and will fly for Mission 2 too later this year. Based on the mass class and known information about the Series 3 lander, it seems similar to or borrowing from the Series 2 / APEX lander being developed by ispace US for an upcoming NASA CLPS mission via partner Draper.

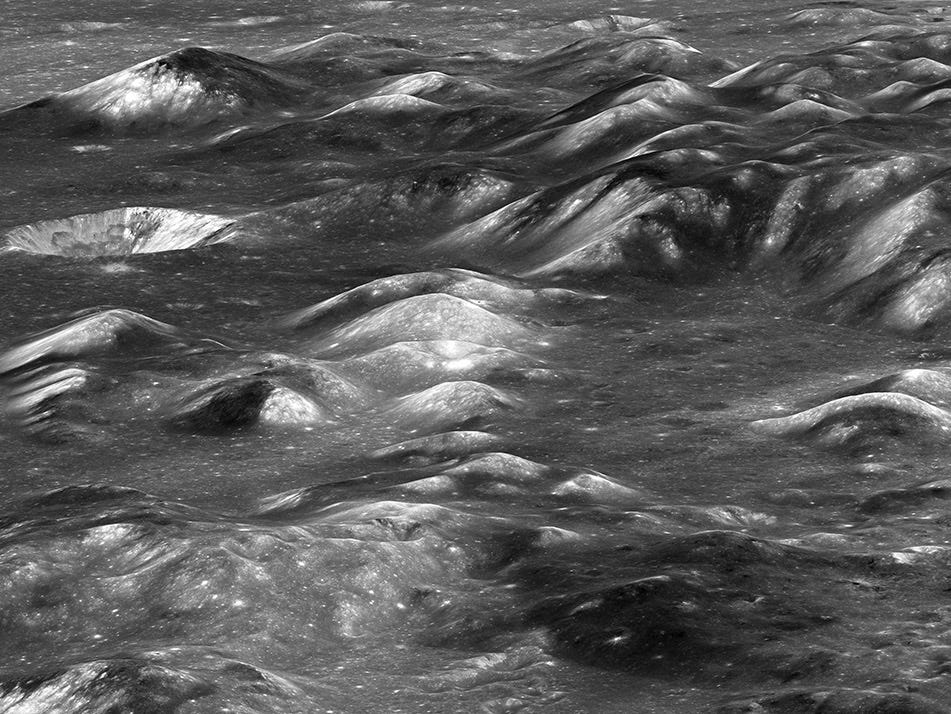

Explore the Moon’s mountains

- With cool elevation graphs and pictures, Jim Singh explores our Moon’s highest, lowest, and tallest spots. 🌖📏

- The intense way Moon mountains form ☄️…💥

- Gallery: Luna’s marvelous mountains 🏔️✨

More Moon

- At the second workshop of multiple countries that have signed the US-led Artemis Accords, hosted by CSA from May 21–23, officials from 24 nations discussed how countries exploring the Moon should avoid interference with activities of others doing so, could have better interoperability, and can share scientific data as widely as possible, all building upon the bare minimum set of mission information expected to be shared publicly such as expected launch dates, the nature of mission activities, and landing sites.