Moon Monday #132: India and the Artemis Accords, mission updates, and more

Thank you so much everyone for your kind notes on Moon Monday crossing 5,000 readers :). Considering the upcoming wave of exciting Moon missions from around the globe, I’m gathering feedback on how I can continue uniquely serving lunar and space communities with this one-of-a-kind newsletter. I request you to take this private, 2-minute survey to that end:

On NASA’s desire to have India sign the US-led Artemis Accords, and clearing misconceptions

Bhavya Lal, NASA’s associate administrator for technology, policy, and strategy told PTI on June 16 that the agency wants India to sign the US-led Artemis Accords to ensure sustainable lunar and space exploration:

I think signing the Artemis Accords should be a priority for India. I mean, NASA feels pretty strongly that India is a global power. It’s one of the few countries with independent access to space, has a thriving launch industry, has been to the Moon, and has been to Mars; it needs to be part of the Artemis team.

[…]

It’s about how we make sure space remains sustainable for future generations. So, I think the benefit is that like-minded countries that have similar values have a chance to explore together.

This urge from the highest ranking Indian American within NASA is bound to stir up discussions and sentiments within decision makers at ISRO and at large the (Indian) Department of Space. This is a great time to list below high-level facts as well as some indispensable considerations when talking about the Accords and India, complete with links for your perusal. I’ll also attempt to clear a few common misconceptions.

- There is international concern that the Accords ultimately might—but doesn’t yet—put its signatories in objection of the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, particularly by controversially setting potentially dangerous long-term precedence for local resource extraction, ownership, and therefore de facto governance on the Moon. Simply put, many would much prefer an international regime be setup via the UN COPUOS instead of relying on bilaterally mounted consensus. While such a process would be slow, the outcome should by definition be more acceptable to the over hundred member states of COPUOS rather than just the US allies.

- India’s new space policy, out in April, states for the first time the country’s novel ambition to extract, use and sell space resources, which also implies utilizing lunar resources. While the policy is yet to morph into a bill, its language is right in line with the respective national bills passed by four signatories of the Accords: the US, Japan, Luxembourg, and UAE.

- India has signed—but not ratified—the 1979 Moon Treaty, which has strict and even highly idealistic non-sovereignty underpinnings that fundamentally do not gel well with the Accords. The US has explicitly formally stated it doesn’t support The Moon Treaty. If India signs the Accords, it might either need to consider withdrawing from the Moon Treaty just like Saudi Arabia did or join Australia and France as the only other such countries trying to walk on thin lines. It’s possible to pursue forming an international lunar regime via the Moon Treaty, which India, France, and Australia might act on.

- Many countries who have signed the Accords aren’t conducting any substantial space activities—much less lunar ones—or plan to anytime soon. The Accords is primarily a geopolitical instrument, and will be seen as such before its potential utility as a science & technology collaboration framework.

- In a March 2022 interview, ISRO Chief S. Somanath said that the agency has submitted an internal report to the Indian government regarding possible stances the country could take on the Accords. Relatedly, the Takshashila Institution has published an interesting SWOT analysis of India signing the Accords versus taking other routes. The document also highlights several shortcomings of the Accords, such as it lacking a formal mechanism to resolve disputes.

- Having said all that, a country signing the Accords is not a prerequisite for it to collaborate with NASA on Artemis missions, the context of which is captured well by Marcia Smith in a December 2022 report. In any case, said fact is also evident when you simply look at existing Artemis collaborations, wherein many countries aren’t signatories of the Accords. Germany in particular stands out like a sore thumb. Relatedly, the Accords aren’t binding anyway, and so India could continue pursuing collaboration with other countries such as Russia if it wants to.

- Between the Chandrayaan 1 lunar orbiter and the upcoming high-profile NISAR Earth observation satellite, India-US space relations have continued to grow in the past two decades. At the same time, the sour relations between India and China make their collaboration on the Sino-Russian International Lunar Research Station unlikely. India’s traditionally strong space ties with Russia have also been dwindling in favor of the US, and so faster due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- As part of a new US-India partnership on some “critical and emerging technologies”, the two nations decided in January to identify possible contributions from ISRO and Indian aerospace companies to NASA’s CLPS program, which aims to regularly, commercially send payloads, instruments, and hardware to the Moon on privately built US landers. But no single company is known to be identified yet. While many such India-US collaborative frameworks for science and space exploration already exist, they may not carry the momentum of being an Accords signee.

- The Accords could fast-track India’s planetary exploration and human spaceflight capabilities and ambitions, and do so cost-effectively, via collaborations with not just the US but other members of the Accords as well. As Pradeep Mohandas notes, such exploration partnerships would notably include the Quad countries of the US, Japan, India, and Australia. All quad members but India have signed the Accords.

- Japan and India are already collaborating on the LUPEX Moon rover mission to study water ice on the Moon’s south pole. It’s targeted for launch in the 2026–2028 timeframe. LUPEX, similarly to NASA’s VIPER rover, aims to help scientists unravel the physical and chemical nature of the Moon’s water ice deposits, assess their realistic resource potential, and determine how accessible they really are to help us plan future crewed missions. If VIPER somehow fails, LUPEX stands to provide NASA, via JAXA, a second and more cost-effective chance at obtaining the desired critical data on which Artemis crewed missions will rely.

- A direct NASA-ISRO collaboration with India’s Chandrayaan 2 lunar orbiter for Artemis represents an untapped opportunity, especially as US scientists have formally urged NASA to replace the gracefully aging, 2009-launched Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. The upcoming robotic & crewed Artemis Moon missions will need continued and advanced orbital data support, for which said US scientists recognize the abilities of the Chandrayaan 2 orbiter in their report. For both the US and India, the Artemis Accords could catalyze this collaborative end. What’s in it for India though? Other than the country’s budding planetary science community being infused with a wealth of LRO-derived operational and scientific knowledge, it would lend India a seat on the table for polar resource prospecting to ultimately help shape resource extraction governance as and when it happens.

I hope these points illustrate the impetus but also the challenges for India to sign the Accords, and thus how it isn’t a straightforward decision for the country as is being otherwise often assumed, implied, and expected.

Many thanks to Epsilon3 for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday.

Mission updates

- ULA Chief Tory Bruno said on June 13 that the March 29 blowing up of a test Centaur V upper stage of their new Vulcan rocket was due to a super thin steel skin of the hydrogen tank being a bit too thin. This means ULA will need to redo pressure testing of at least a new Centaur V structure if not also the flight version of the long-awaited inaugural Vulcan launch carrying Astrobotic’s first Moon lander. On June 7, ULA completed the long-awaited hot fire test of the two main engines powering Vulcan’s first stage. But with the Centaur changes, Eric Berger says two of his sources indicate a Q4 Vulcan launch. Astrobotic’s first Moon lander will carry NASA CLPS payloads and commercial, international ones too.

- Hardware progress continues for NASA’s Artemis II mission to fly four astronauts around our Moon and back circa early 2025. On June 14, ESA formally handed over the 15,000-kilogram European Service Module (ESM) to NASA. ESM will provide propulsion, water, oxygen, thermal control, and electrical power to the Orion crew capsule hosting the astronauts. As part of an ongoing series of standard space-simulating tests, NASA completed launch acoustic testing of the ESM in May. The ESM will undergo more tests, including separate deployment and inspections of its four solar arrays, before being mated with the crew capsule in the coming months.

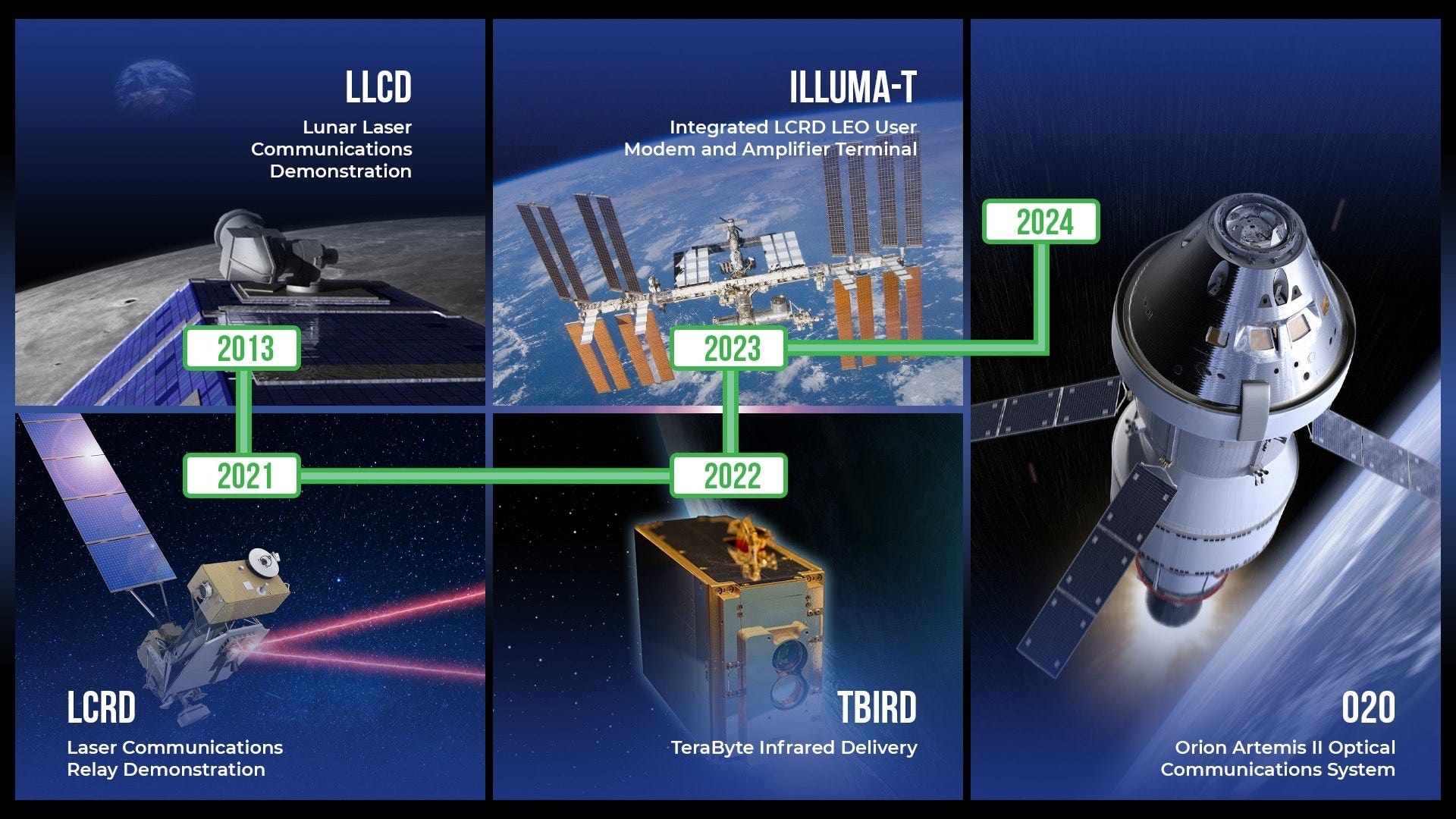

- Relatedly, the NASA-MIT-developed optical laser communications terminal called O2O passed space testing and has been delivered for integration with the Artemis II Orion crew capsule. It’s a technology demonstration to send more data with lower size, weight, and power requirements compared to traditional radio transmission systems. During the mission, NASA hopes to beam 4K HD videos and pictures during minimal cloud coverage at likewise suitably selected two ground stations. This demonstration is part of the agency’s Space Communications and Navigation (SCaN) program’s optical infusion effort, which has been demonstrating laser communications on multiple missions.

More Moon

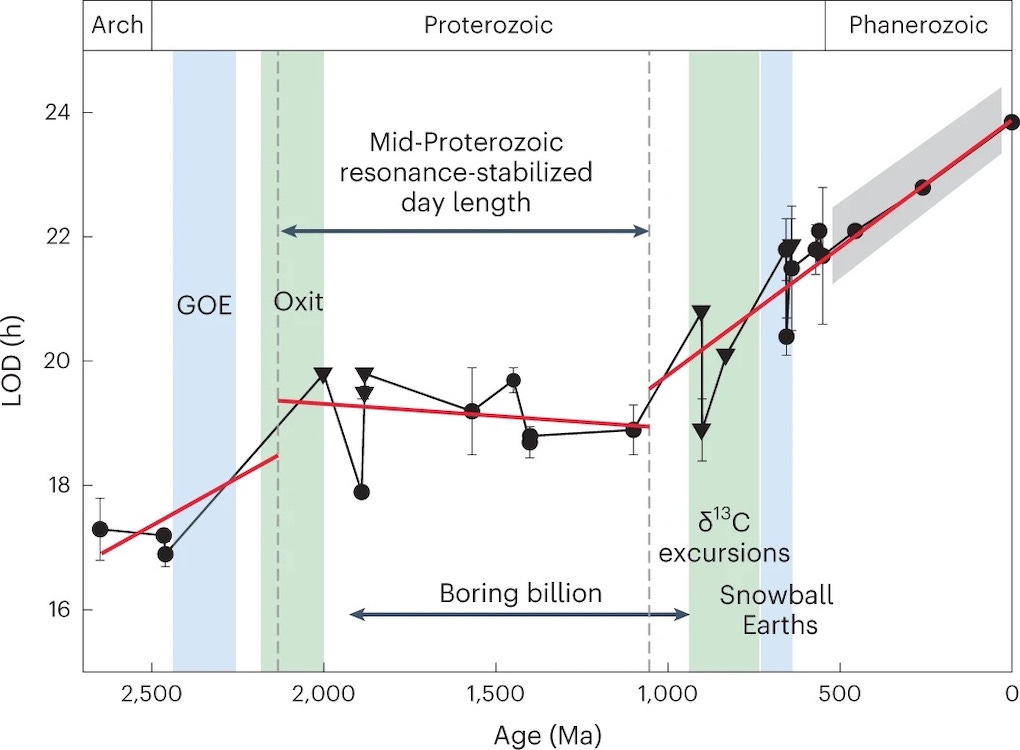

- The fact that our Moon has been absorbing Earth’s rotational energy, slowing our planet’s spin to the current 24-hour day while boosting itself to a higher orbit, may not have always been a gradual process. In a study published on June 12, scientists examine ample rhythmic layering within special sedimentary rocks to infer that roughly between two to one billion years ago, resonance between solar and lunar tides caused the Earth’s day to remain frozen at around 19 hours. Matt Williams from Universe Today has explained and contextualized the findings well.

- Cislune has won four $150,000 NASA grants to advance on specific problems across the spectrum of advanced lunar exploration technologies: from ensuring minimal water ice loss during resource excavation to designing launchpads that minimize threats of regolith blasts from landers.

- A new paper by Dagomar Degroot, an environmental historian at Georgetown University, says NASA’s “planetary protection” efforts to quarantine Apollo 11 astronauts after returning from the Moon were mostly for show.