Moon Monday #261: A shortfall in Artemis II testing and NASA’s communications

Dear NASA, China’s space missions exist too. So do your own planetary science missions.

Launch of Artemis II astronauts delayed

NASA’s fueling test of the SLS rocket on February 2 in preparation to launch the Artemis II mission to fly four astronauts around the Moon and back did not go as planned. There were repeat hydrogen leaks beyond acceptable thresholds at multiple points despite trying gentle liquid hydrogen flows and all such related techniques NASA tried during Artemis I, which itself needed seven fueling attempts across months to then finally have the rocket fly. The core leak area this time was the same that nagged Artemis I, the tail service mast umbilical at the bottom of the SLS rocket’s mobile launcher used for fueling. Stephen Clark noted how the core objectives of the test at the end of the launch countdown couldn’t be met:

The objective was to stop the countdown clock 33 seconds prior to launch, about the same time the rocket would take control of the countdown during a real launch attempt. Instead, the clock stopped at T-minus 5 minutes and 15 seconds. NASA said the countdown terminated “due to a spike in the liquid hydrogen leak rate.” The countdown ended before the rocket switched to internal power and fully pressurized its four propellant tanks. The test also concluded before the rocket activated its auxiliary power units to run the core stage’s four main engines through a preflight steering check, all milestones engineers hoped to cross off their checklist.

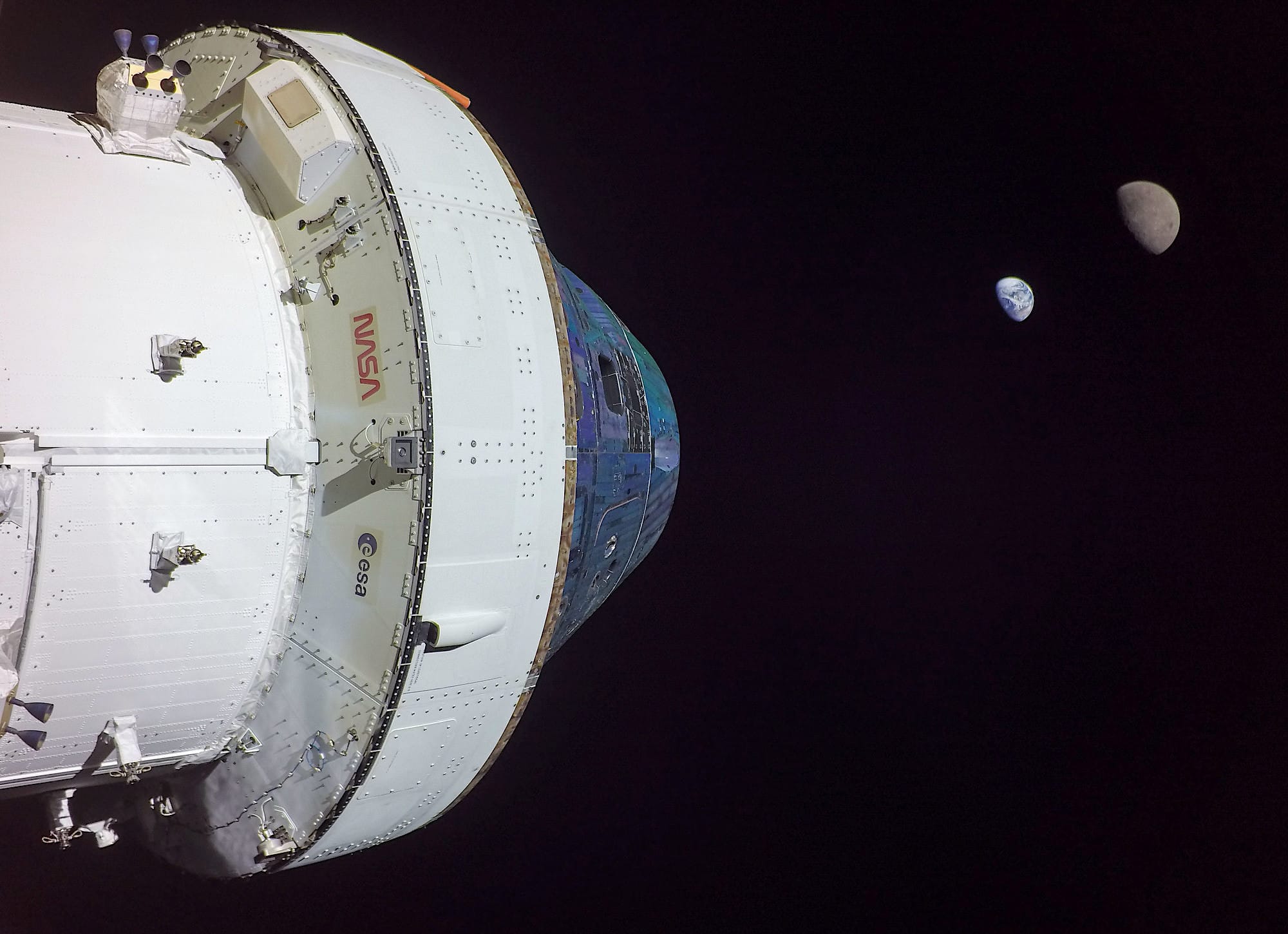

NASA did achieve two other aspects of the test: 1) a specialized team went up the launcher and closed the Orion spacecraft’s hatches as they would on launch day for astronauts inside the capsule, and 2) safe defueling of the SLS rocket. Teams then began reviewing the test data to form mitigation plans, and will return for a fueling test at some point before setting an official target launch date, which now can be March at the earliest.

Dear NASA, Chinese space missions exist too

NASA recently published a post on how the agency will track the Artemis II mission using a network of ground stations. In the release, NASA included the following statement [emphasis mine]:

Orion will experience a planned communications blackout lasting approximately 41 minutes. The blackout will occur as the spacecraft passes behind the Moon, blocking radio frequency signals to and from Earth. Similar blackouts occurred during the Apollo-era missions and are expected when using an Earth-based network infrastructure. When Orion reemerges from behind the Moon, the Deep Space Network will quickly reacquire Orion’s signal and restore communications with mission control. These planned blackouts remain an aspect of all missions operating on or around the Moon’s far side.

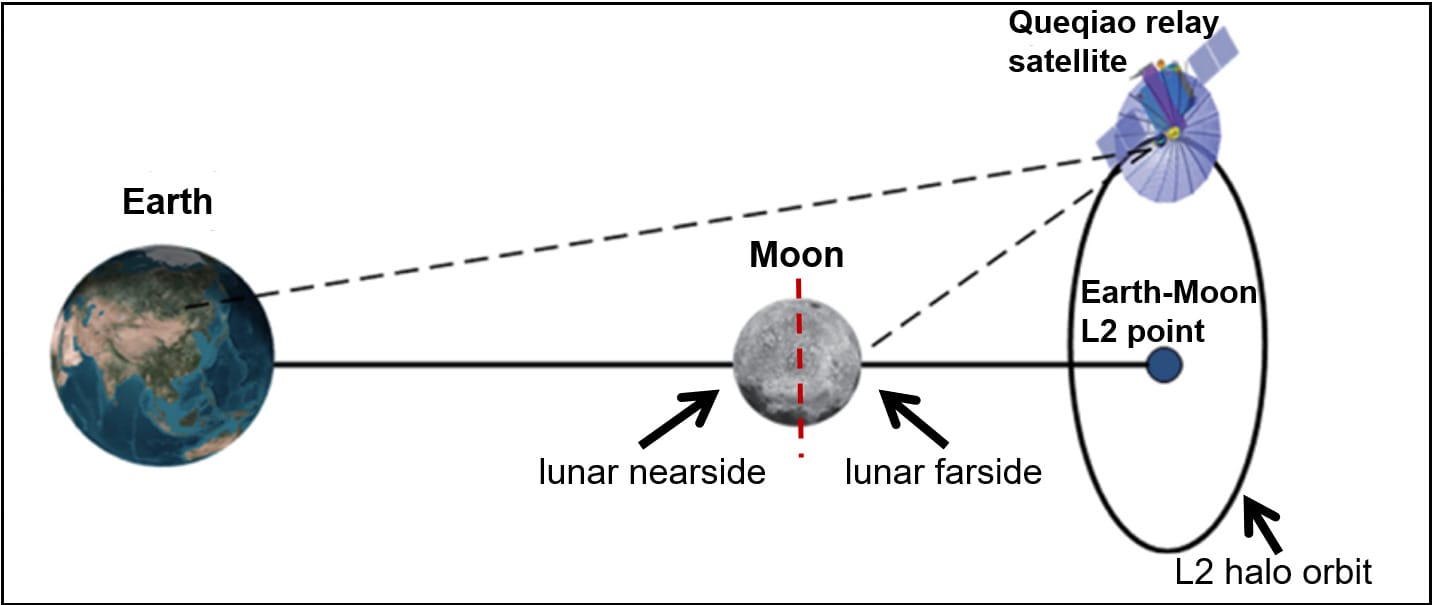

All missions? These kinds of blackouts have been solved by China, who have had two relay satellites, Queqiao 1 and Queqiao 2, for communicating with its Chang’e 4 and Chang’e 6 landers respectively on the lunar farside. As such, NASA saying that the blackouts remain an aspect of all farside missions is incorrect. The statement needs to be qualified by noting that the issue stands for all US missions.

This isn’t the first time NASA has made statements about global missions while discarding what China does or aims to. In 2024, when the US agreed to land Japanese astronauts on the Moon in return for Japan providing an advanced pressurized crewed rover for the Artemis program, the announcement called “a Japanese national to be the first non-American astronaut to land on the Moon”, conveniently ignoring China’s plans to land astronauts on Luna end of decade.

What science will Artemis II do? Zilch?

NASA has proudly pioneered effective science and technical communications with the public for decades, elevating understanding of space exploration worldwide. But the agency’s communications over the last few years haven’t been as eloquent, with fluffy narratives taking the driver’s seat even in aspects that aren’t politically charged. This is the case with Artemis II as well. When inaugurating the Artemis Science Team Flight Control Room in June 2025, NASA wrote the following in a release on its website:

Artemis II astronauts will observe the Moon during their 10-day mission around the Moon and back, taking photographs and verbally recording what they see. Their observations will support science objectives and provide data for potential landing sites for future Moon missions.

Now, Artemis II is not even an orbiter mission. The four astronauts inside the Orion capsule will be flying more than 7000 kilometers from the Moon at their closest approach. What science can they even do from such large distances? And so in less than 10 days? Certainly no landing sites will be selected.

For selecting actual landing sites, NASA has used over a decade worth of observations from its Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) which flies within 100 kilometers of the Moon’s surface. NASA is also getting aid from India’s Chandrayaan 2 orbiter to leverage its superior imagery and radar system for filtering Artemis landing site candidates. Are we now supposed to believe that a few days worth of Artemis II observations several thousands of kilometers from the Moon will help NASA select landing sites? This fluffy communications ultimately disrespects NASA’s own LRO efforts.

There is a nuanced element to the Artemis II observations. All Artemis II activities will certainly be useful operationally to feed forward into coordinating the science team with astronauts on Artemis III and missions beyond. But doing science as an objective in itself is a different ballgame altogether. There are also limits to what a few days of coordination can teach us when astronauts are this far from the Moon. The work that the science team is doing is important but not for the fluffy reasons being conveyed by NASA around this topic.

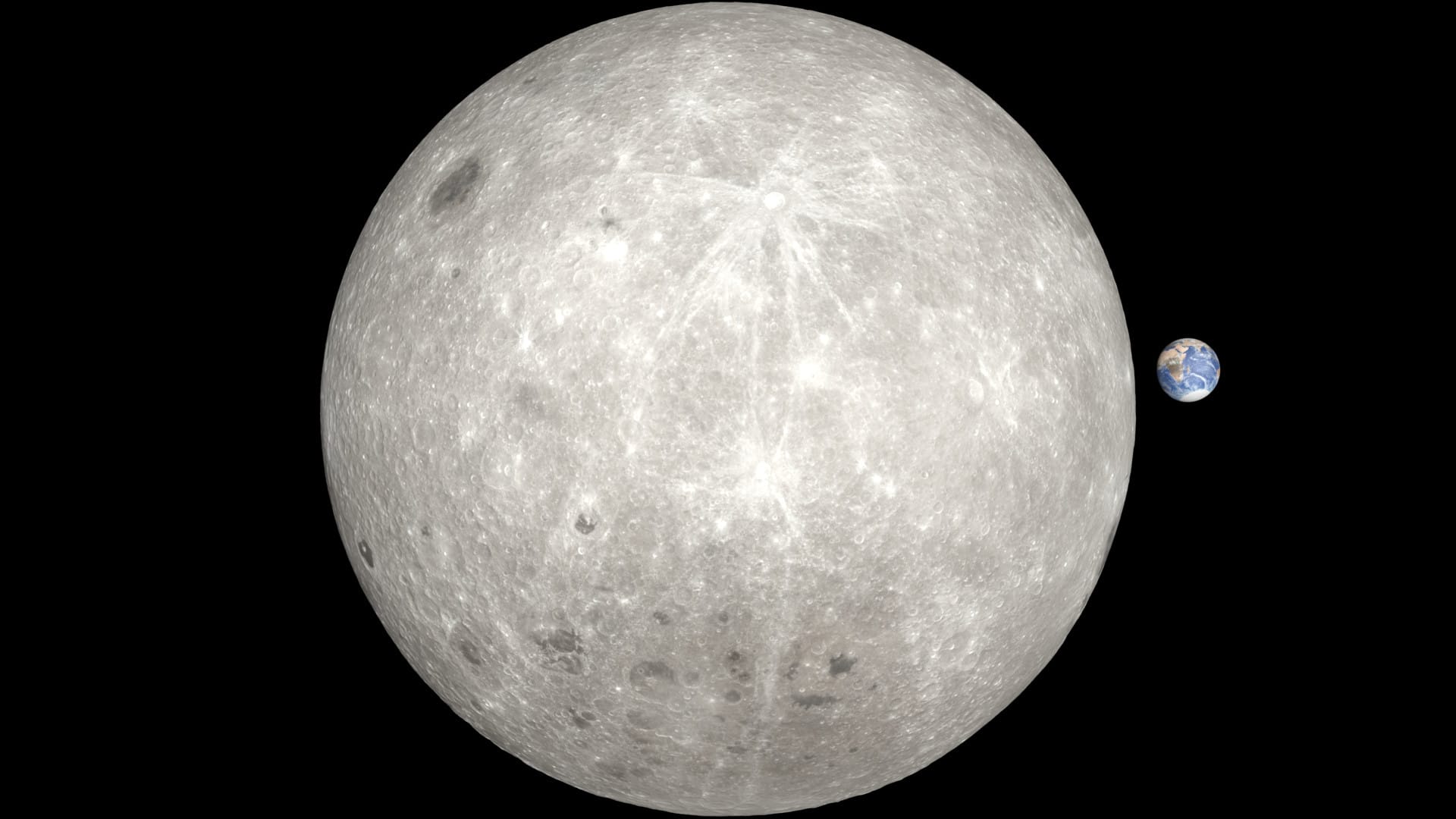

Of course, like the beautiful images from Artemis I, views of the Moon and our Earth from near Luna can have great impact on people’s minds. With Artemis II, we have an opportunity again to view our Moon and Earth through the eyes of astronauts, and their iPhones, building on the beauty of the Apollo 8 Earthrise. As such, Artemis II’s lunar observation campaign has a lot of emotional value. It just doesn’t have a scientific one, especially when the same agency does real science missions.

Now, every space agency does PR pieces. But NASA’s science communications have had the highest bar. We should hold them to that high standard while pushing other agencies to match.

Many thanks to The Orbital Index and Deepika Jeyakodi (who kindly wishes me to link to the cause of PARI instead) for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday.

If you too appreciate my efforts to bring you this curated community resource on global lunar exploration for free, and without ads, kindly support my independent writing: