How NASA has planned to keep Artemis II astronauts safe throughout their Moon mission

Moon Monday #260: Safety planning spans all phases and aspects of the crewed lunar mission, weaved into hardware, operations, and astronaut training. 🦺

Disclaimer for transparency: Open Lunar has been one of the sponsors of Moon Monday for about five years now. As such, my public Editorial Independence Policy has applied to my coverage of Open Lunar too, and will continue to. This includes continuing to disclaim about them being a sponsor of any kind every single time I mention their work just as I’ve been doing all year last year.

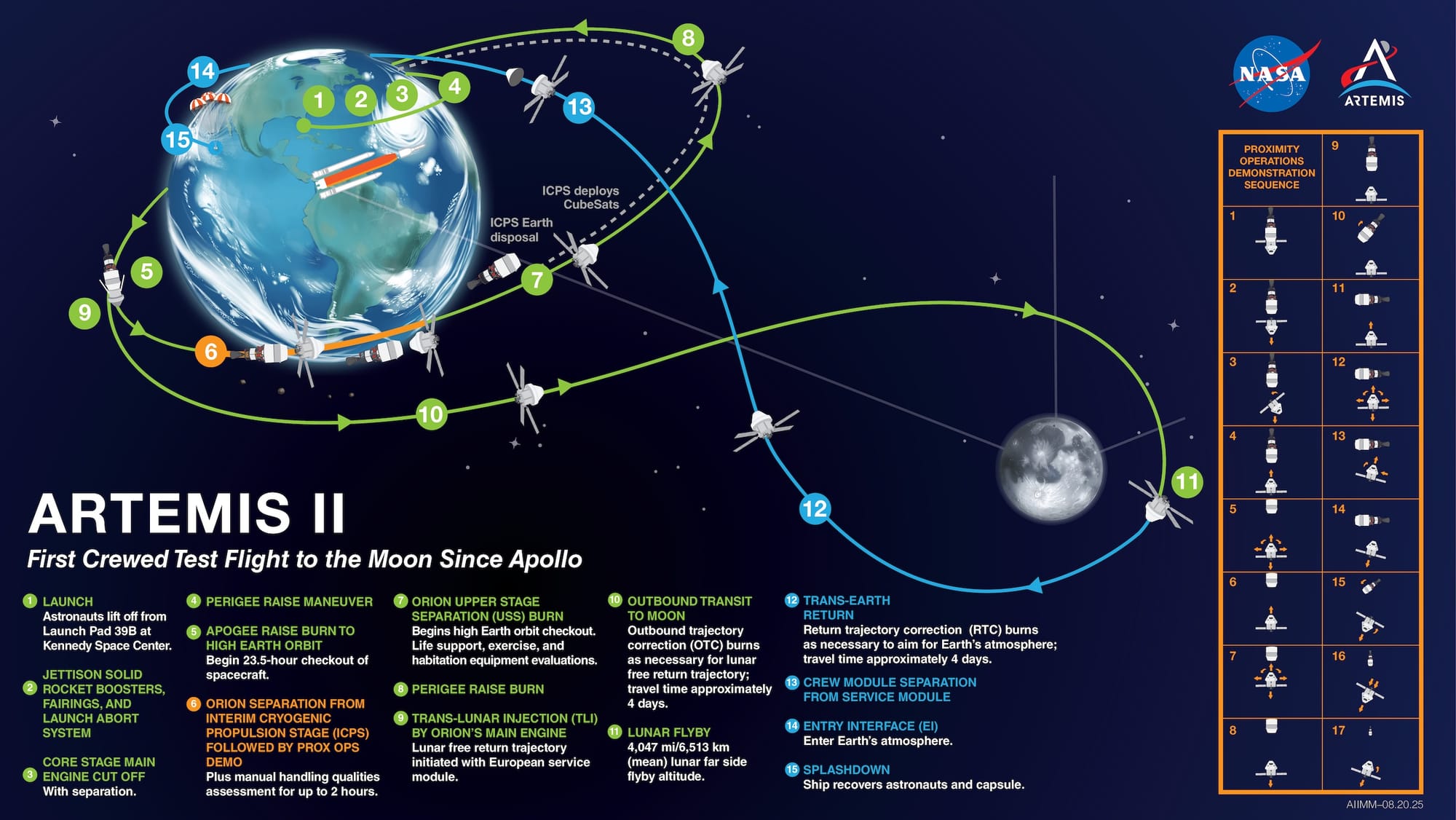

On February 1, NASA powered up the SLS rocket’s core stage at its launchpad at the agency’s Kennedy Space Center in Florida. Today, February 2, the agency began preparing for a fueling, launch countdown, and defueling test suite. If this “wet dress rehearsal” with cryogenic propellants is successful, the agency is clear to launch the Artemis II mission to fly four astronauts around the Moon and back, knowing that the launch procedures are working as expected. The earliest possible launch dates for the astronauts are February 8, 10, and 11, each having five-hour windows. If the wet dress rehearsal finds issues to be fixed, the next available launch dates are in March and April.

In the meanwhile, astronauts remain in quarantine to keep them safe against exposure to pathogens. To ensure the astronauts are safe and keeping well during the entire mission, NASA has planned to guard many aspects at once. Other than having global-standard safety measures like an emergency rocket escape system for the Orion crew capsule and an urgent launchpad egress system for astronauts, NASA has also developed systems to have real time monitoring of the Artemis II mission and its crew so as to tweak things as needs arise.

This applies to pre-launch preparations too. The SLS rocket’s aforementioned fueling test was delayed to stick to the mission’s weather criteria amid cold conditions and avoid potentially unwarranted effects on the mission hardware while also ensuring testing in conditions similar enough to actual launch. NASA also noted the following in an update on January 26:

During an evaluation of the emergency egress system, the baskets used to transport the crew and other pad personnel from the mobile launcher in an emergency stopped short of the terminus area located inside the pad perimeter. Since then, the brakes of the system have been adjusted to ensure the baskets fully descend.

The astronauts have also been trained to handle various permutations of such escape scenarios. Teams at NASA also work to ensure the crew’s Orion spacecraft and its life support systems keep functioning nominally, as noted in the same release:

In the coming days, technicians also will take additional samples of Orion’s potable water system to ensure the crew’s water is drinkable. Initial samples showed higher levels of total organic carbon than expected.

This brings us into the next aspect, monitoring the health of the astronauts themselves during the mission. To that end, NASA includes a wristband and multiple advanced tools for astronauts to check their physiological patterns. Since space and payload mass aboard Orion is limited, many of these experiment packages are miniaturized versions of those previously flown on the International Space Station. Some of them will report metrics and outputs in real time for NASA to monitor while others will be analyzed post-flight.

Radiation protection

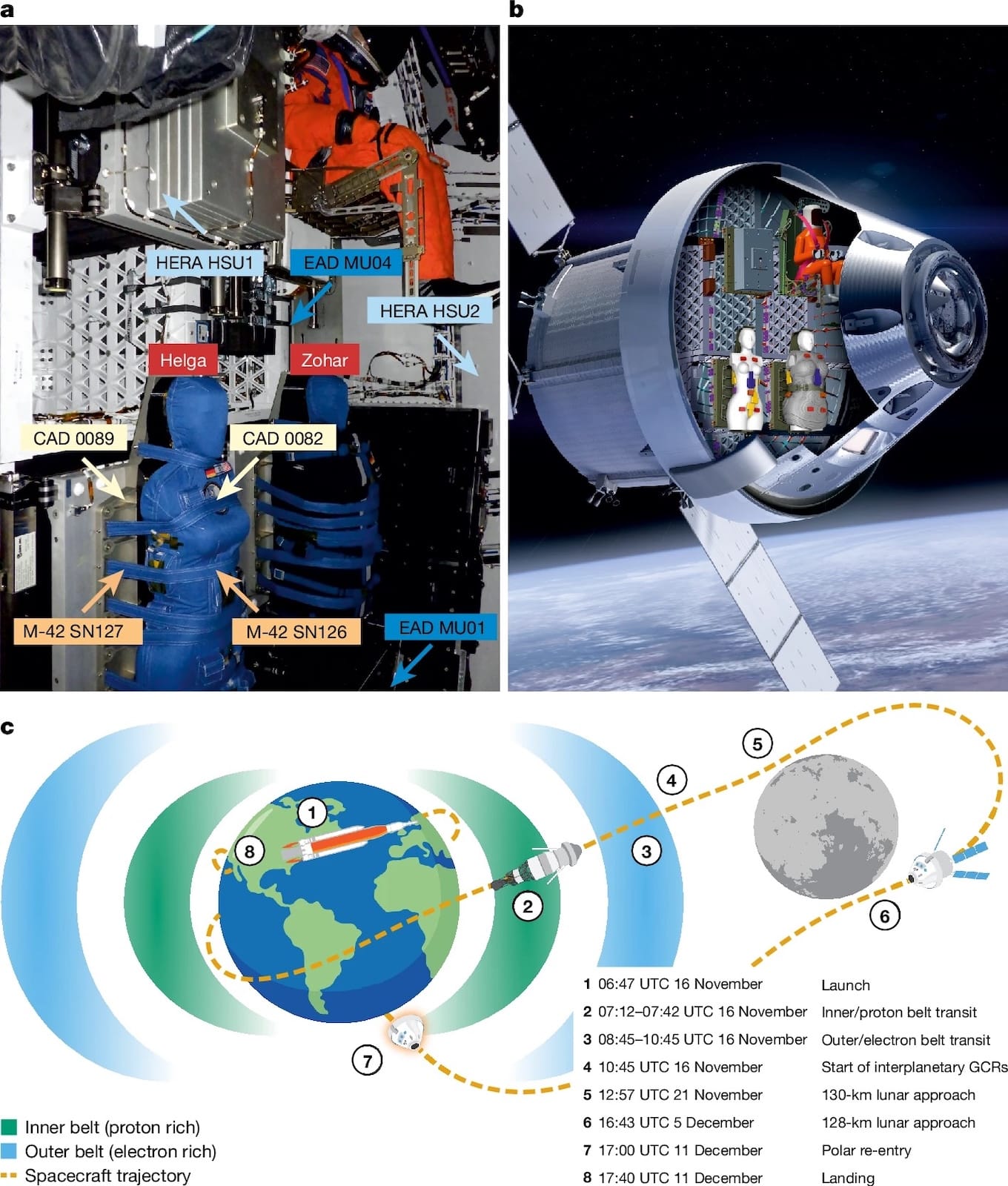

Given the scarcity of data on human health in lunar and deep space environments, Orion will carry even more radiation sensors than on Artemis I to review post-mission. A notable upgrade comes from a partnership with the German Space Agency (DLR):

NASA has again partnered the German Space Agency DLR for an updated model of their M-42 sensor—an M-42 EXT—for Artemis II. The new version offers six times more resolution to distinguish between different types of energy, compared to the Artemis I version. This will allow it to accurately measure the radiation exposure from heavy ions which are thought to be particularly hazardous for radiation risk. Artemis II will carry four of the monitors, affixed at points around the cabin by the crew.

This collaboration builds on results from Artemis I whose radiation data was evaluated by NASA, ESA, and DLR scientists last year. They found that radiation exposure to future astronauts will vary not only based on time spent at locations within the capsule but also on Orion’s orientation in space. For example, the paper says when Orion’s orientation was altered during an engine burn, exposure levels dropped nearly in half due to the highly directional nature of the radiation in the Van Allen belt. NASA will continue to study lunar and deep space radiation environments with scientific payloads on the upcoming NASA-led Gateway orbital habitat.

From August 4 through 7 in 1972, the Sun blurted several bursts of flares and associated energetic particles between the Apollo 16 and 17 missions to the Moon. Had the astronauts been in lunar orbit or on the surface, they could’ve faced damaging levels of radiation. This could, in turn, lead to increased cancer risk. Likewise, radiation particles from such strong solar events can reach Artemis II astronauts within hours. Since we are around the peak of solar activity in this cycle, teams will be monitoring bursts from the Sun that might pass through Orion in its flight paths. Sensors onboard Orion will also provide warnings when radiation influx crosses a certain threshold. For such events, NASA’s strategy is for the crew to increase their radiation protection by repositioning items inside Orion:

To protect themselves, astronauts will position themselves in the central part of the crew module largely reserved for storing items they’ll need during flight and create a shelter using the stowage bags on board. The method protects the crew by increasing mass directly surrounding them, and therefore making a denser environment that solar particles would have to travel through, while not adding mass to the crew module itself. If the warning were to sound, the crew would create the shelter within an hour and in some cases would need to stay inside for as long as 24 hours.

Mission monitoring

In terms of real-time monitoring of the mission, there are specific aspects too. For example, in Eric Berger’s interview of the Artemis II astronauts last year, which provided a good rundown of the mission’s timeline and key checkpoints & fallbacks post launch, the Mission Pilot Victor Glover shared an interesting detail:

The first workout [for astronauts] is a checkout of that exercise hardware, but it's also a checkout of the environmental control system. Because I'm going to be breathing, I'm going to be sweating, making more humidity and more CO2 for the life support system to scrub out. And then if that's good, that's another check that means we can go to the Moon.

Back to a broader scale, NASA built a new Orion “Mission Evaluation Room” (MER) at the agency’s Johnson Space Center which didn’t exist for Artemis I. NASA built MER last year to complement flight control teams during the mission. The MER team comprises about 48 engineers from across NASA, ESA, Lockheed Martin, and Airbus with deep knowledge of Orion’s subsystems. They will analyze technical data as the mission unfolds, assisting flight control with optimizations as well as any anomalies.

Complementary to MER is NASA having trained the astronauts to fly Orion in a realistic emulator:

Inside the Orion Mission Simulator at Johnson, the crew [has] rehearsed every phase of the mission, from routine operations to emergency responses. Simulations are designed to teach astronauts how to diagnose failures, manage competing priorities, and make decisions with delayed communication from Earth.

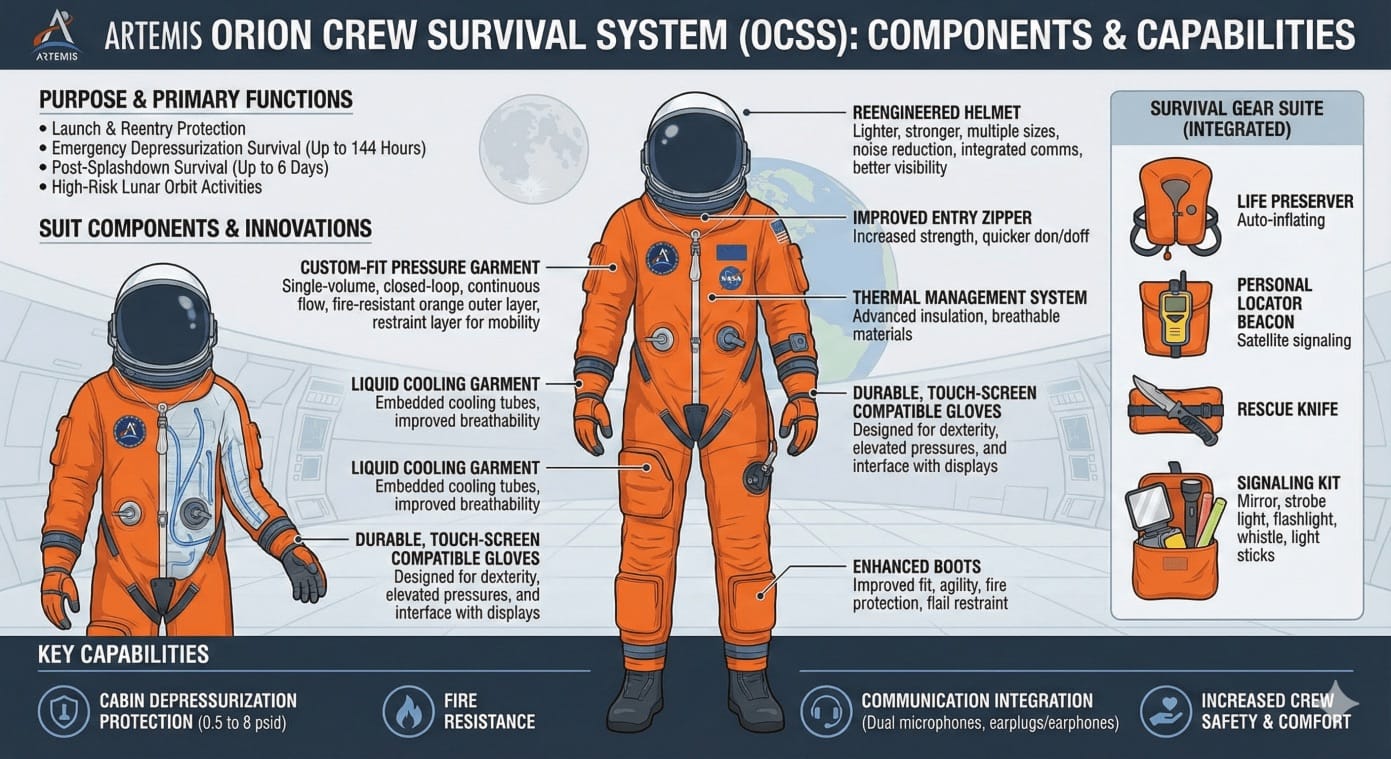

For the most happening events during the mission, like the tumultuous launch and the fiery atmospheric reentry, NASA has developed the Orion Crew Survival System (OCSS). It’s a specialized spacesuit with a flame-resistant outer layer which astronauts will wear during such mission phases to protect themselves against potential anomalies. Astronauts would also wear OCSS if other high risk events occur during the mission since the suit is their lifeboat if and when critical systems in Orion fail. It may seem like an extended feature but it’s quite central to astronaut safety. From a 2019 NASA release:

Even though it’s primarily designed for launch and reentry, the Orion suit can keep astronauts alive if Orion were to lose cabin pressure during the journey [...]. Astronauts could survive inside the suit for up to six days as they make their way back to Earth.

This pairs well with another safety aspect of the mission. NASA has designed a free return trajectory for Orion’s flight around the Moon such that if the spacecraft’s engines stopped working for some reason, Orion will be pulled back towards Earth due to the net result of the natural gravitational forces acting on the craft. The OCSS can keep astronauts alive amid several such anomalies near the Moon.

The OCSS suit can also help the astronauts after splashdown on Earth. From NASA:

The suits are also equipped with a suite of survival gear in the event they have to exit Orion after splashdown before recovery personnel arrive. Each suit will carry its own life preserver that contains a personal locator beacon, a rescue knife, and a signaling kit with a mirror, strobe light, flashlight, whistle, and light sticks.

Should there be some issue or delay for the recovery teams and their vessels to arrive post-splashdown, the astronauts have been trained to stabilize the capsule if necessary, exit it, and board a raft on their own and then use the OCSS survival kit as necessary. Their suits are also bright orange to make them easier to spot amid ocean waters.

Communicating with Orion

Getting back to the mission-wide systems, NASA will track the Orion spacecraft near-continuously and ensure safety of the astronauts by having multiple communications channels. Chiefly, NASA will use a combination of its Near Space Network (NSN) and Deep Space Network (DSN) to track the mission. Managed by the agency’s Goddard and JPL centers respectively, these networks have antennae spread worldwide so that Orion can be in reach despite facing any part of Earth.

Orion will also carry a NASA-MIT-developed optical laser communications terminal called O2O to send some mission data independently, albeit it’s primarily intended to be a test. O2O aims to demonstrate sending more data with lower size, weight, and power requirements compared to traditional radio systems. During the mission, NASA hopes to beam 4K HD videos and pictures during minimal cloud coverage over to likewise two suitably located ground stations. This demonstration is part of the agency’s Space Communications and Navigation (SCaN) program’s optical infusion effort, which has been demonstrating laser communications on multiple missions. However, the Artemis III Moon landing mission will not have a laser communications unit from NASA.

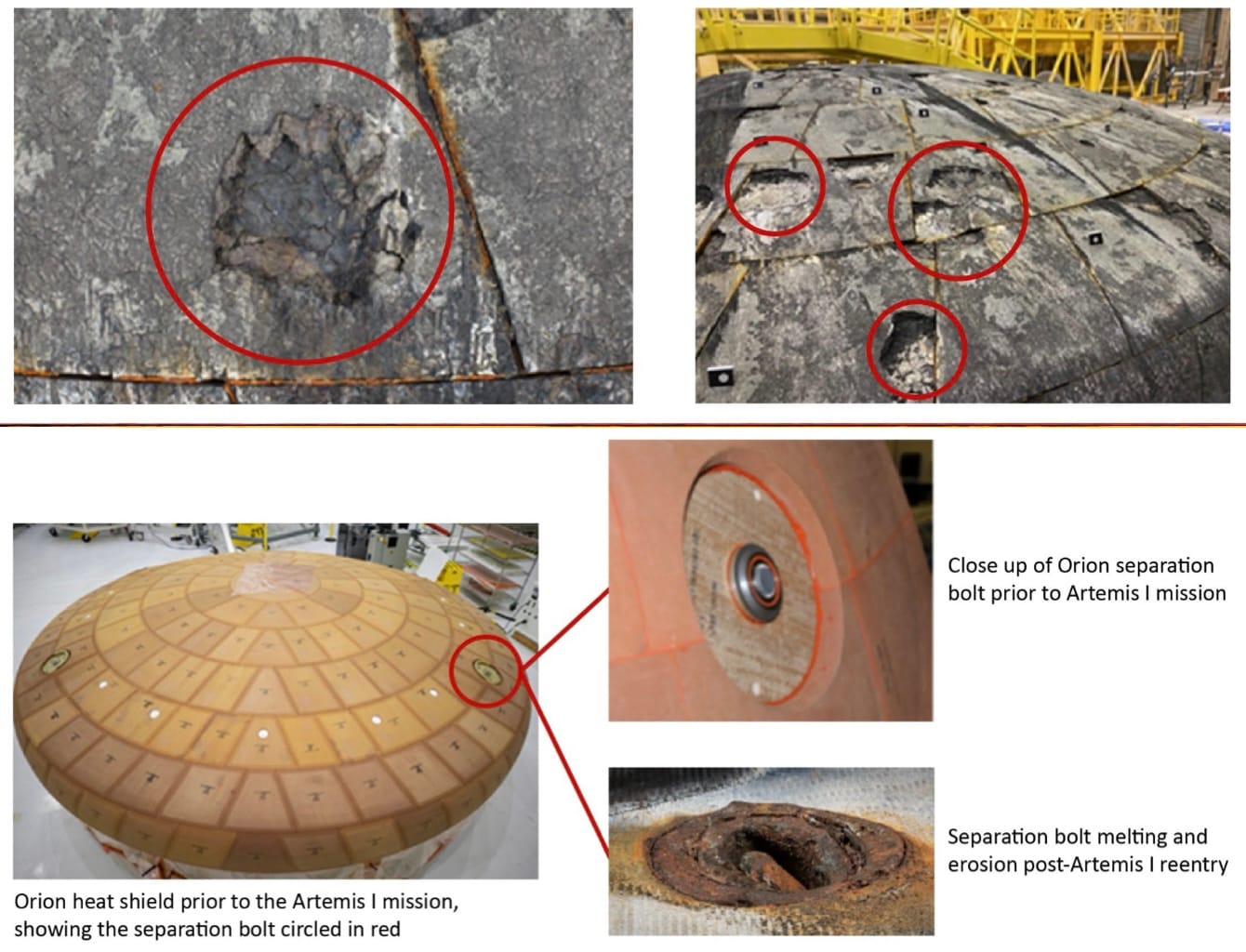

The heat shield

And now we come to the final major aspect, the one that’s been contended publicly: the Orion capsule’s heat shield. Two independent investigations by NASA circa 2024 analyzed the unexpected damage caused to Orion’s shield during reentry in 2022 for the uncrewed Artemis I Moon mission. The agency concluded that the heat shield’s ablative Avcoat material was not porous enough to vent and dissipate hot gas buildup during its bounced atmospheric reentry, which led to cracks and loss of entire chunks. NASA then decided to change Orion’s reentry profile for Artemis II to manage the heat buildup, deeming it a safe measure for astronauts.

Jared Isaacman’s first priority after becoming the NASA administrator in December 2025 was to review Orion’s heat shield and its effectiveness in saving the lives of Artemis II astronauts during atmospheric reentry. NASA decided that the altered reentry profile proposal would work. Eric Berger, one of the two reporters with (preferential?) access to the review meeting, noted the worst case scenario as follows:

The NASA engineers wanted to understand what would happen if large chunks of the heat shield were stripped away entirely from the composite base of Orion. So they subjected this base material to high energies for periods of 10 seconds up to 10 minutes, which is longer than the period of heating Artemis II will experience during reentry. What they found is that, in the event of such a failure, the structure of Orion would remain solid, the crew would be safe within, and the vehicle could still land in a water-tight manner in the Pacific Ocean.

Not all experts seated in the meeting were convinced, with one publicly citing limitations of the tools used for said analyses. Here’s hoping the Artemis II astronauts fly and get back to Earth safely.

On the other hand, there’s poignant irony in unequivocally debating so much about saving the lives of astronauts but not of those on the ground too, including not only having protective measures for launch teams but also looking out for the safety of passengers in flight against rocket debris, engineers on ground testing hardware, and simply caring about lives of people at large. The pursuit of space does not place us above human life.

Many thanks to Open Lunar Foundation, Gurbir Singh and Henry Throop for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday! If you too appreciate my efforts to bring you this curated community resource on global lunar exploration for free, and without ads, kindly support my independent writing: