Moon Monday #230: China leaps again in its steady march to Luna while NASA’s progress on Artemis remains a mixed bag

A look at recent Chinese milestones in the build up to crewed lunar missions, another blow(up) for Artemis, how Firefly’s Ocula can fill critical gaps for NASA, and more.

On June 18, China successfully conducted a launchpad escape test of its next-generation Mengzhou spacecraft, variants of which will carry astronauts on future Earth orbit and Moon missions. A video from CCTV+ shows how everything seems to have functioned as planned across the eventful two minutes: from the escape to the ascent to the drogue & main parachute deployments and—last but not the least—the airbag-cushioned capsule landing.

Notably, Chinese engineers have designed the emergency escape to be handled by the spacecraft itself instead of the rocket. This makes it somewhat launch vehicle agnostic, giving China flexibility to scale its crewed Moon mission plans in the run up to the China-led ILRS Moonbase ambitions. The China Manned Space Agency (CMSA) has thus noted that the successful test has “laid an important technical foundation for the subsequent manned lunar exploration missions.”

Jack Congram notes the following in his detailed coverage of the test (which is relevant because China will launch its crewed lunar missions from Wenchang):

A few days ahead of this test, China Central Television released a report regarding launch escape systems for crewed spacecraft, which briefly touched on Mengzhou’s launch system. That report notes that due to the density of launch infrastructure at Wenchang, Mengzhou’s escape systems boasts a higher thrust-to-weight ratio, compared to Shenzhou, to pull the spacecraft out toward the ocean quickly. Additionally, the report stated that should a launch abort be triggered late into flight, Mengzhou’s propulsion systems on the service module can propel the spacecraft a safe distance away or into orbit.

The escape test is the latest in a series of design validations for Mengzhou, most notably including the high velocity capsule reentry test in 2020. Once a few final tests planned later this year are complete, China is targeting flying crew on Mengzhou for Earth orbit missions next year. This will also help characterize the vehicle’s performance in space as well as refine its operations before a variant carries Chinese taikonauts to lunar orbit before 2030.

More Sino milestones for crewed Moon missions

- With Chang’e 5, China demonstrated the world’s first remote docking and undocking of spacecraft in lunar orbit in 2020. It repeated the feat with Chang’e 6 last year, bringing lunar samples from the Moon’s farside and demonstrating flexibility in the core architecture. China will utilize the technology for crewed Moon landings, wherein a “Mengzhou Y” spacecraft will dock with a “Lanyue” lunar lander in lunar orbit. Two of three/four astronauts then transfer into the lander. After the two spacecraft separate, the Lanyue lander will touchdown on the Moon for the surface mission. It will then return to lunar orbit for re-docking with Mengzhou, which will subsequently bring the crew back home.

- Late last year, China created a test stand which can simulate the kind of high-altitude and vacuum conditions that the Lanyue lander will go through during its lunar descent and touchdown. The stand allows the lander’s main engine to be tested for its full burn duration of up to 20 minutes. Apparently the test system took only eight months to complete, according to Li Guanghui from CAST.

- Andrew Jones reported in November 2024 that CALT successfully conducted a 5-meter-fairing separation test of China’s upcoming heavy-lift, crew-capable Long March 10 rocket. The Long March 10 will also have a three-booster variant with a larger fairing for crewed Moon missions, whose separation system will be tested soon too as per CASC. Two Long March 10 mega rockets will launch Mengzhou Y and Lanyue towards the Moon respectively.

- With the debut launch of the semi-cryogenic Long March 12 rocket last November, China successfully flew the YF-100K engine, the same kind that will power the first stage(s) of the Long March 10.

- Ling Xin reported in July 2024 that China successfully test fired the high-energy hydrolox YF-75E engine as well. Three of these engines will power the third stage of Long March 10.

- The upcoming Chang’e 7 and Chang’e 8 missions, targeted for launch next year and 2028 respectively, will demonstrate precision landing as well as the ability to explore the Moon’s south pole for water ice and other resources. Both of these will be valuable for China’s ILRS Moonbase plans with crew and robots.

- China has demonstrated world-leading lunar navigation and communications systems in complex Earth-Moon orbital spaces. It’s bound to substantially improve both the surface coverage time and area as well as ground station availability for China’s future crewed lunar missions.

- Development has also progressed for the space suit and rover to be used by astronauts.

The last time China conducted a launchpad escape test was in 1998. Five years later, it flew its first astronaut to Earth orbit. With 2025 marking the completion of the critical escape tests for China’s next-generation crewed vehicle, the country has yet again set a target of five years within which to send humans to the Moon. It might just do it.

Many thanks to Gurbir Singh and Sanket Suman Dash for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday! If you too appreciate my efforts to bring you this curated community resource for free and without ads, support my independent writing. 🌙

Another blow(up) for Artemis

An upper stage of SpaceX’s Starship Super Heavy rocket exploded on June 19 during preparations for a static fire test that’s conducted pre-launch. The explosion may have been caused by the failure of a high-pressure nitrogen tank in the vehicle’s payload bay. SpaceX said shortly after that no people were lost in the incident, which happened on the test stand called Massey’s. It lies several kilometers away from the Starship launch site. As Stephen Clark points out, the test stand was the only place for SpaceX to static fire Starships and validate their functioning before taking them to the launchpad. As such, SpaceX is left without a facility at the moment to support preflight testing of Starships.

The incident marks the fourth failure in a row for the Starship program this year. The upper stage on the ninth Starship Super Heavy launch on May 29 failed due to a fuel leak and loss of attitude control. The booster was lost too due to anomalous engine re-lighting after reentry. The mission couldn’t achieve any of its key objectives: from opening the payload bay door and ejecting simulated satellites to testing heat shield tile reentry experiments to safely bringing back a previously flown booster. The two flights prior to it failed as well.

Due to SpaceX’s failures this year, NASA’s long road to putting humans on the Moon with Artemis III via an inching Starship has slowed down even more. While the Moonsuits being made by Axiom Space has been facing its own delays, Starship now seems to be the pacing item for NASA to land humans on the Moon this century. Given the numerous milestones left before a Starship can carry astronauts to Luna, it may not be ready in time to meet the US’ self-imposed goal of “beating China” to the Moon.

Related:

- How China has an edge over the US in sustaining future crewed Moon missions

- How Western media narratives of Chinese lunar activities misjudge capabilities and intent

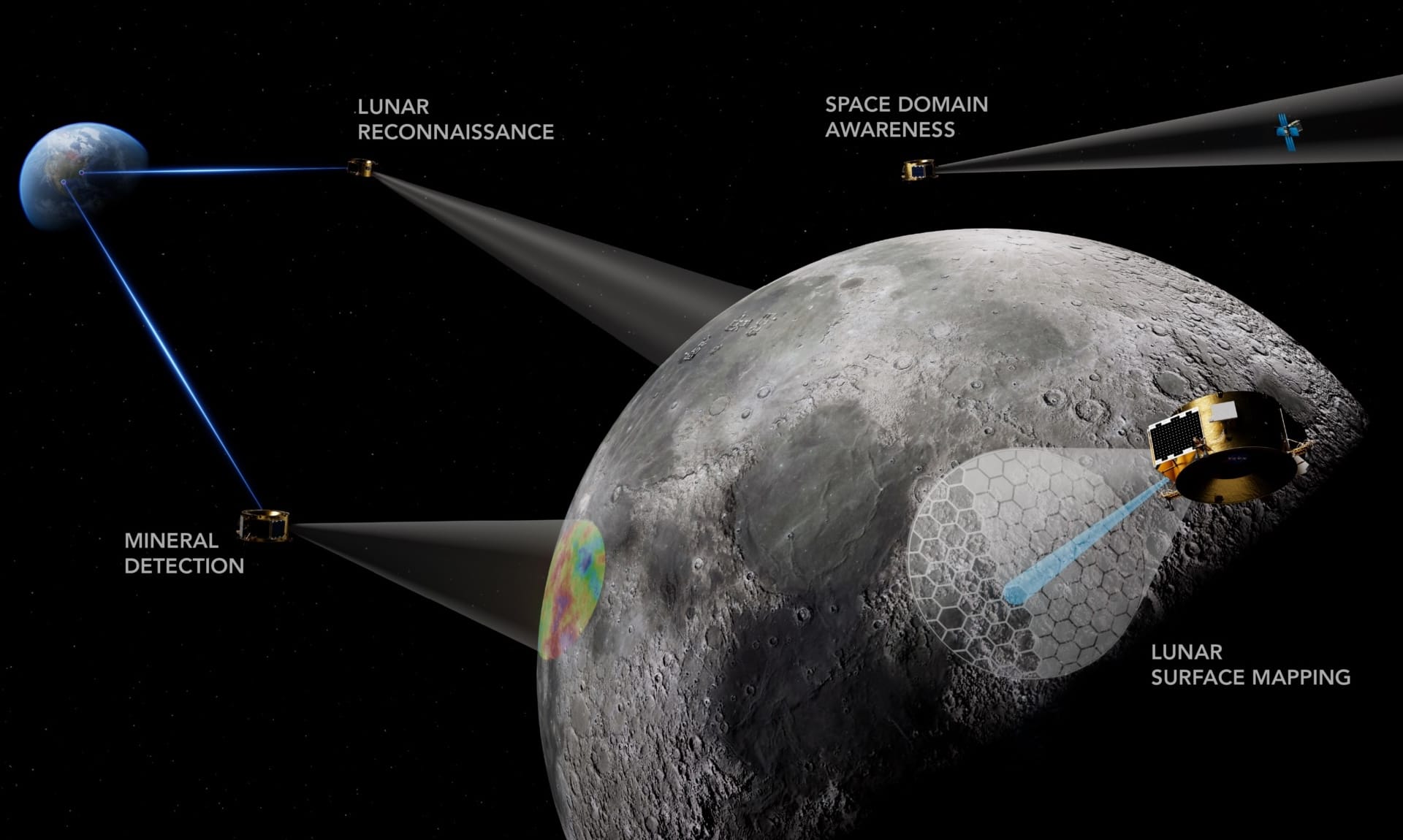

The silver Ocula to fill some gaps for NASA

US-based Firefly announced a commercial lunar imaging service called Ocula to succeed parts of the role that NASA’s gracefully aging Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) has played for US and international Moon missions by providing high-resolution lunar surface imagery and topographic information. Firefly says the imaging with mineral detection capabilities will commence with its first Elytra Dark spacecraft next year from low lunar orbit. The orbiter will do so after completing its services for Firefly’s upcoming second Moon lander mission part of NASA’s CLPS program.

Firefly says Ocula’s best case optical imagery will tout a resolution of 20 cm/pixel, more than twice as good as the 50 cm/pixel LRO provides at its sharpest. If achieved, it would also be bit sharper than the current best of 25 cm/pixel that ISRO’s Chandrayaan 2 orbiter pulls off. In fact, NASA has been collaborating with ISRO to have the Chandrayaan 2 orbiter aid Artemis landing site selections with lunar polar water prospecting and hazard classifications. But NASA’s leveraging and ISRO’s promoting of the orbiter’s optical and radar capabilities have been limited in scope. In the meanwhile, the 2009-launched LRO is due for its final mission extension evaluation with limited capabilities left, and can no longer maintain an orbit that can study the lunar poles heads down in any case.

Recognizing these constraints, a specialized team of US scientists released a report in 2022 urging NASA to plan replacing the LRO with a multi-orbiter approach so as to support the increasingly complex and diverse upcoming robotic and crewed Moon missions. Three years since, NASA has not approved any LRO successor despite the LExSO mission being proposed by members from the LRO team itself. NASA’s budget request for FY2026 too does not ask for any funding for the same. As such, Firefly’s Ocula service could fill some of that gap for US missions, closing some critical cases. But other shortfalls will remain since Ocula is not a full-fledged reconnaissance orbiter. For those, NASA and ISRO could tighten their use of the Chandrayaan 2 orbiter for Artemis, using it as a de facto LRO replacement and enhancement especially for helping locate water ice on lunar poles—something the US has been failing at despite it being central to Artemis.

Related: Lunar science galore from Chandrayaan 2

More Artemis updates

- Astrobotic announced that its first CubeRover has successfully passed the standard suite of space environmental tests ahead of its upcoming flight on the company’s Griffin lander heading to the Moon’s south pole as part of NASA CLPS. The large lander’s primary payload will be the FLIP rover by Astrolab (a Moon Monday sponsor), which got manifested recently after NASA decided not to fly the VIPER rover aboard Griffin. Astrobotic also announced that it has successfully completed a high fidelity hardware-in-loop simulation of Griffin’s navigation and landing systems all the way up to an emulated touchdown.

- This month NASA, the US Department of Defense, and Artemis flight control teams are practicing emergency procedures at sea that they would use to rescue the Artemis II crew from their Orion capsule after a launch emergency—either one on the launchpad or after liftoff. The recoveries use a mock Orion spacecraft with similar exterior to emulate the capsule and mannequins to simulate crew.

- In similar vein to ESA’s LUNA Moon-simulating facility, NASA opened up a new facility to simulate the high contrast, high shadows lighting environment at the Moon’s south pole that the Artemis astronauts will face.

- Interlune, one of the several lunar water startups developing resource extraction and excavation technologies for the Moon, is hiring a planetary scientist to lead work on lunar regolith and soil simulants. The company is also hiring an operations manager and a mechanical engineer.