Moon Monday #229: China extends lead in lunar orbital infrastructure, gets an edge in future crewed missions over the US

Plus: Examples of how Western media narratives of Chinese lunar activities misjudge capabilities and intent

Before we begin this week’s Moon Monday, consider taking a moment of silence for everyone affected by the deadly Air India flight crash in Ahmedabad on June 12. 😔

Ling Xin reports that on May 22, China moved the Tiandu 1 lunar orbiter from its Distant Retrograde Orbit (DRO) to a 3:1 resonance orbit. This move comes after the small 61-kilogram (at launch) spacecraft helped China achieve the first ever daytime Earth-Moon laser distance measurements using an orbiter earlier this year. In its new orbit, Tiandu-1 loops around Earth thrice for every revolution of the Moon around our planet. It’s a stable orbit, requiring minimal maintenance. It reminds me of how in 2023, ISRO pulled Chandrayaan 3’s propulsion module from lunar orbit to Earth orbit, demonstrating a small but key capability that will be required to pull off a robotic sample return mission in the future with Chandrayaan 4.

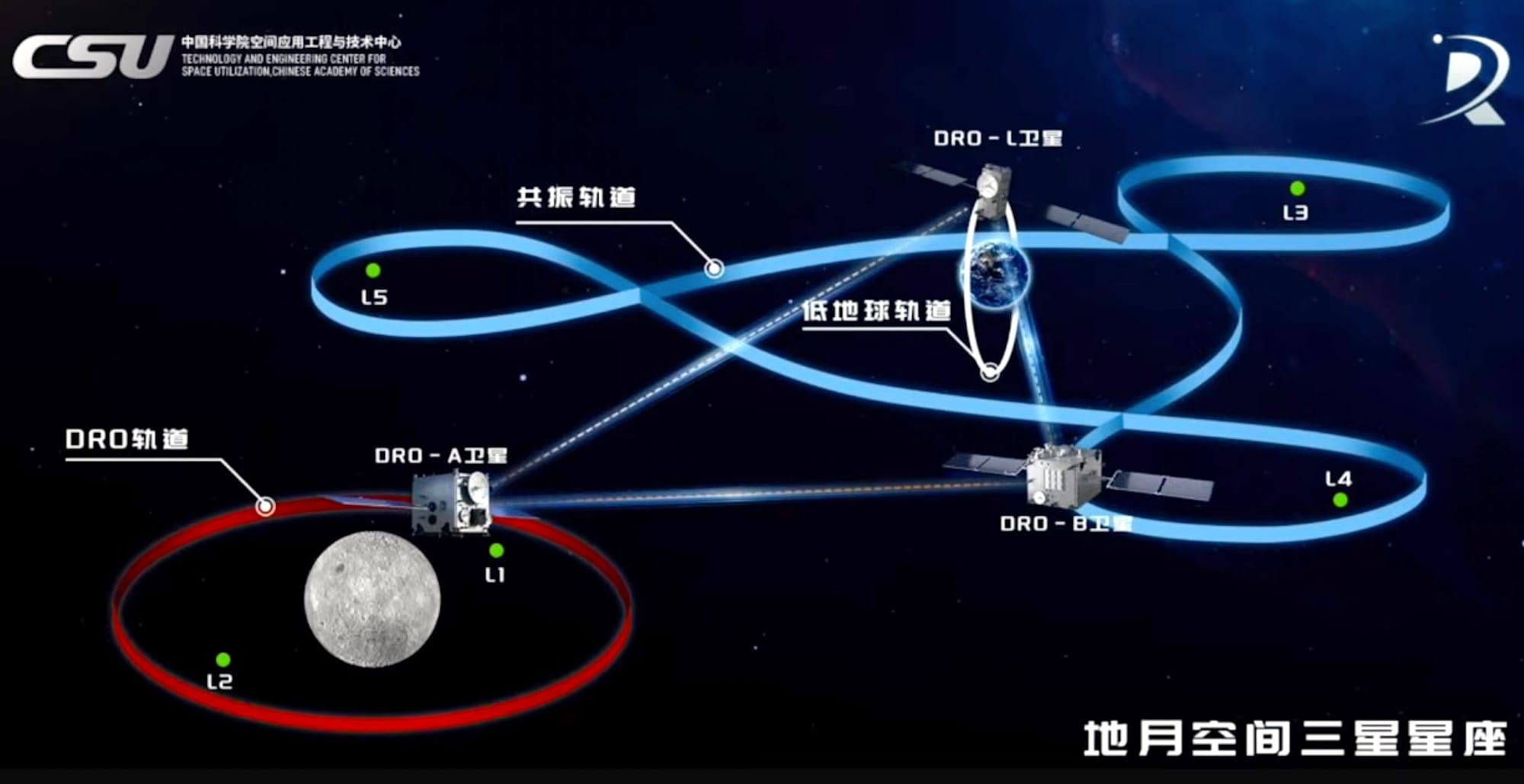

Coming back to China, as per graphics shown by CAS and subsequently reported by others, China also made the DRO-B lunar satellite depart its DRO orbit in April and enter a 3:2 resonance orbit—a world first. When in DRO, the 277-kilogram (at launch) DRO-B and its twin craft DRO-A demonstrated automated navigation at the Moon in tandem with the Earthbound DRO-L satellite. The three satellites tracked each other without relying on Earthly ground stations.

The damaged solar panels of DRO-B post its anomalous launch will reduce the extent of automated navigation the craft can perform in its new orbit but demonstrations and spacecraft operations continue nevertheless. Enthusiastic spacecraft observer Scott Tilley, who has been tracking the aforementioned Mooncraft and independently confirmed their orbits, has pointed out that Chinese researchers recently published a paper on exactly these kinds of orbital maneuvers. And now, China has demonstrated several low-energy orbital transfers as well as autonomous navigation in complex multi-body gravitational environments.

China is doing more still in the Earth-Moon space. CNSA launched the 1200-kilogram Queqiao 2 satellite to DRO last year to support Earth-Moon communications for the Chang’e 6 spacecraft modules to fetch farside lunar samples. With that immediate mission accomplished, the orbiter then began making observations to pursue its other scientific goals. CASC has provided an update on the same with notable statements:

The satellite has been stably operating in orbit for 14 months. [...] The satellite’s extreme ultraviolet camera captured the first global 83.4-nanometer ionosphere image, providing crucial data for studying the impact of solar activity on the plasmasphere. The satellite’s VLBI experiment system, in coordination with the Shanghai 65m Radio Telescope, extended the observation baseline to 380,000 kilometers and successfully observed deep-space targets like radio source A00235 and the Chang’e-6 orbiter.

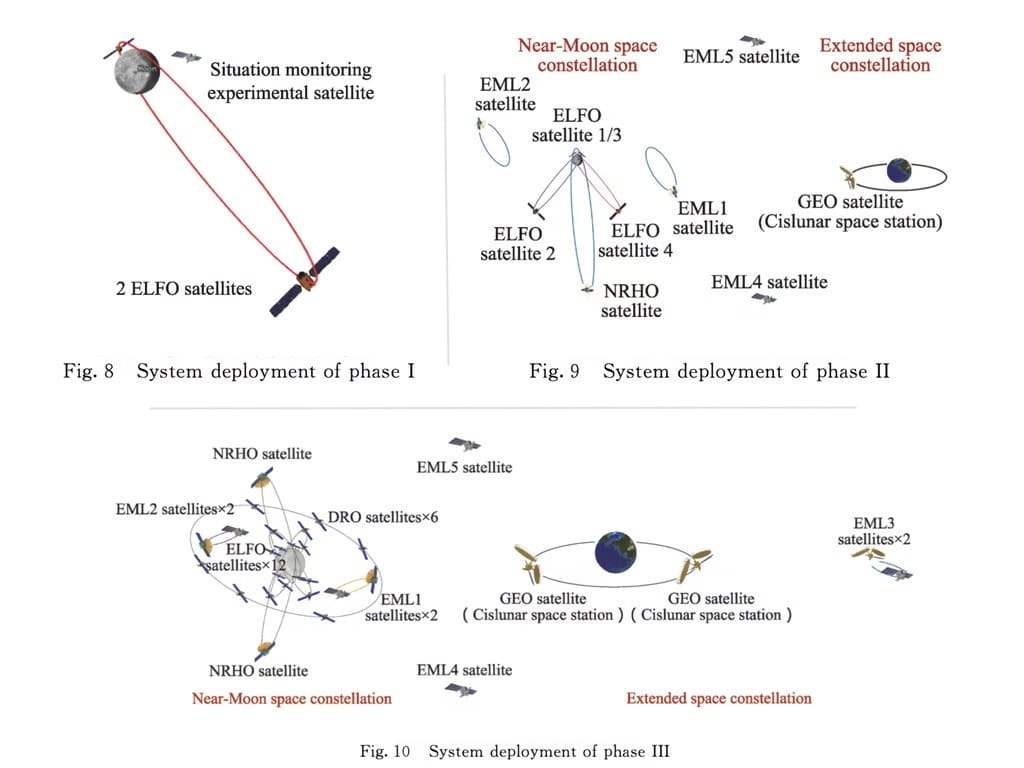

Chinese researchers are expected to publish results based on these observations later this year. Recall that Chinese researchers have suggested that when coupled with Earth-based ground stations, China’s in-progress network of lunar navigation and communications (navcom) satellites can help CNSA track its deep space missions with sub-kilometer accuracy all the way to Jupiter and even beyond. As noted by Chi Wang, et al. in a December 2023 paper, Queqiao 2 will try testing an element of this during the upcoming Chang’e 7 Moon mission:

The LOVEX [payload] on the relay satellite is used to construct a 400000-km baseline Moon–Earth VLBI measurement and observation experiment system to improve the accuracy of orbit determination in deep space and to carry out astrometry and astrophysics observation and study.

How China has an edge in sustaining future crewed Moon missions over the US

Between the developments above, the Queqiao 1 orbiter having enabled humanity’s first lunar farside mission with Chang’e 4, and Queqiao 2 expected to aid the upcoming Chang’e 7 and Chang’e 8 missions to the Moon’s south pole, China has extended its lead in lunar navigation, communications, and complex orbital operations by what seems like a light year.

In the meanwhile, the US has demonstrated a GPS lock on the Moon through private company Firefly’s first Moon lander part of NASA’s CLPS program. But that’s pretty much it. The NASA-funded and Advanced Space-led CAPSTONE lunar orbiter has been making progress towards automated navigation demonstrations with NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) since over two years now. The goal is similar to China’s DRO-A/B/L trio but has a relatively limited scope even when successful. ESA is yet to launch its first lunar communications spacecraft called Lunar Pathfinder as part of its upcoming Moonlight navcom constellation. And so is NASA.

In contrast, China’s visibly great progress in building its full-fledged lunar navcom constellation named Queqiao is bound to substantially improve both the surface coverage time and area for China’s upcoming ambitious crewed lunar missions, which along with robotic explorers systematically lead up to the full-fledged ILRS Moonbase. ILRS is a long-term undertaking, and the Queqiao constellation’s capabilities will afford China redundancy even if—or when—there are ground station availability issues from its Moonbase partners across the globe.

Even if the US somehow lands humans on the Moon first with Artemis III later this decade, the long term game of sustaining human and robotic lunar presence still favors China because it has achieved more complex capabilities in orbital infrastructure as well as modern surface missions, gaining valuable operational experiences therein.

Many thanks to Open Lunar Foundation and Sanket Suman Dash for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday! If you too appreciate my efforts to bring you this curated community resource for free and without ads, support my independent writing. 🌙

A problem with Western media narratives of Chinese space

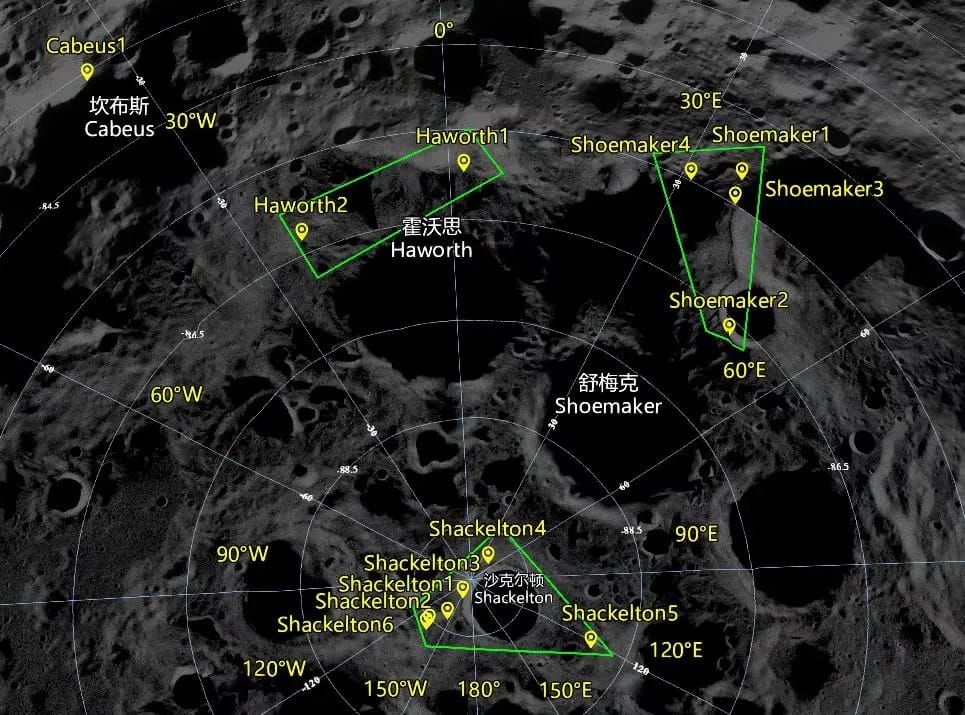

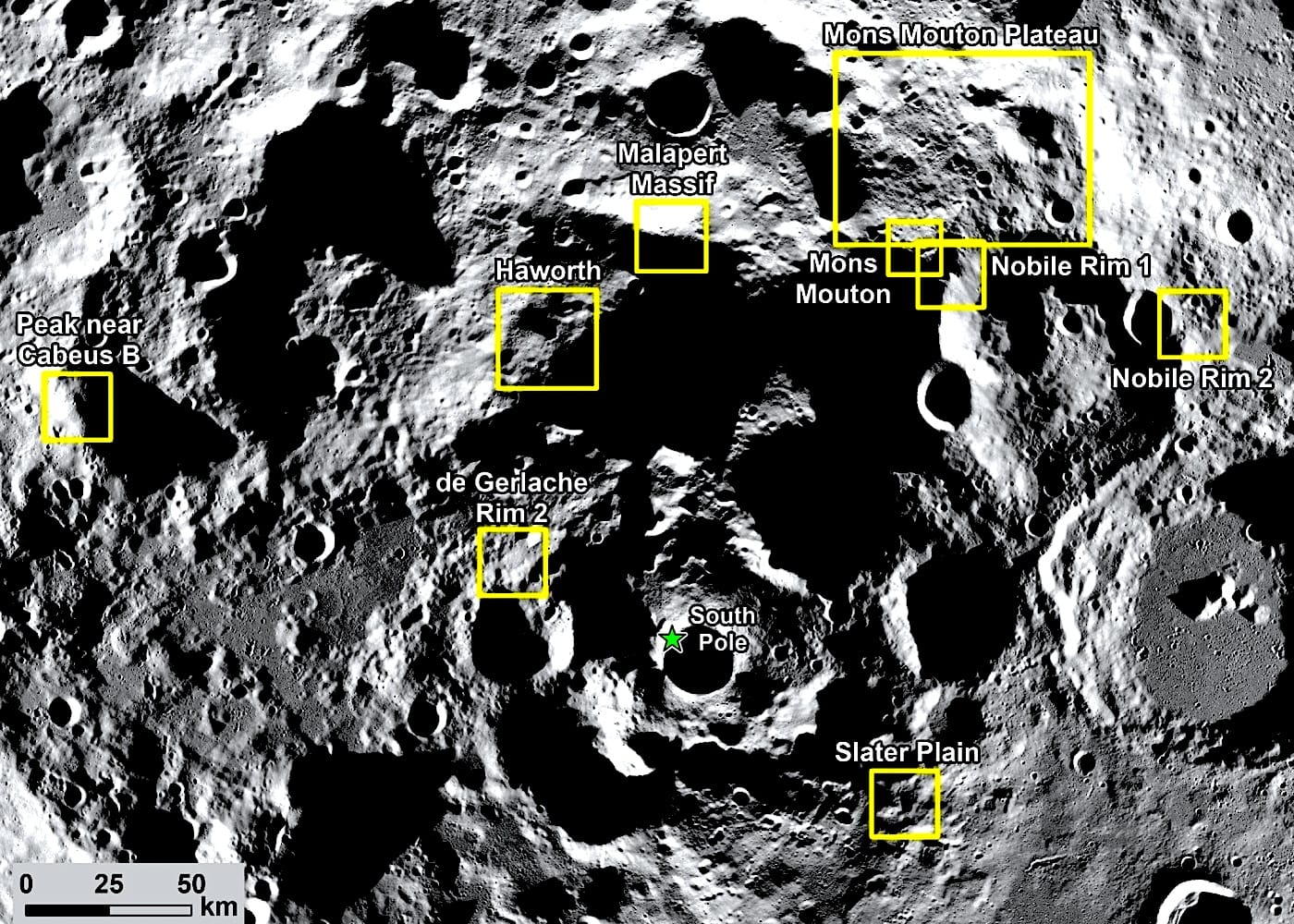

While China has been building up orbital infrastructure for increasingly complex lunar missions, the Western media and industry observers at large have underestimated or ignored the depth of what the Chinese have accomplished at the Moon. Such blindspots usually happen when there’s a fixation on narratives, the kind that lead to fabricating stories such as China choosing “the same” landing sites as the US for its upcoming Chang’e 7 Moon mission. In fact, Gizmodo titled that as “China oversteps NASA in choosing coveted Shackleton crater for its Moon lander”. Such framing is quite questionable:

- Firstly, it was always likely, and known, that the robotic Chang’e 7 would land on the Moon’s south pole before the crewed Artemis III does. So can we even call the former to be choosing “the same” landing site as the latter?

- Artemis III had 13 candidate landing zones in 2022. We’re almost halfway through 2025, and the candidate regions are still a set of nine. It’s not quite a “selection” yet.

- More importantly, Shackleton is a large 21-kilometer wide crater, and the number of mission-favorable areas on the rim and nearby ridges are relatively plenty. Even if both missions ultimately chose Shackleton as the main landing region, they would be reasonably far away from each other not just in time but in space too.

- Similar arguments can apply for Chang’e 8.

While, yes, the water-hosting lunar south pole not being a massive place could eventually mean potential contest between countries—and companies—for some common sites, much before that though comes the fact that there are purely engineering and scientific factors that make landing site selections converge to certain locations. For example, the Sun perpetually circling the lunar polar horizon coupled with rocky terrain automatically render higher altitude areas desirable power-wise for touchdown—which is what most lunar polar missions end up converging to. I highlighted this point in an invited Media Roundtable discussion hosted by the Duke University in 2024:

It’s important to keep in mind that not all decisions are taken with a geopolitical adversary in mind. Some of them are purely engineering. But this you would only understand if you have scientists and engineers talking to policy makers. Fear-mongering narratives can cause issues to scale up, and then convert into a lot of unfriendliness that could impact everyone badly… as journalists, our job is to simplify and clarify the layers of what scientists and engineers do—as well as the geopolitical and policy elements.

Such technical factors should be considered first before jumping the gun with political changes and associated policy recommendations and that maybe based on shallow narratives. It could adversely affect international cooperation and collaboration, both of which are hard won, while making discussing real challenges more difficult. We shouldn’t have to waste our time and efforts discussing laughable claims like China apparently landing Chang’e 6 in the farside Apollo crater just to signal the US of a race.

It can be helpful to get some non-US perspective here. Jack Congram, who writes the blog & newsletter “China in Space” with the aim of providing more grounded coverage of Sino space activities, offers a view on this Moon “race”:

While the US has tried to lean on the idea of competition to secure political and financial support, China treats its space and lunar programs as part of long-term plans for national development. [...] With few political shifts and more stable funding, China doesn’t need to frame its lunar program in a race with the US plans.

[...]

Once a policy and its direction are decided, it tends to receive consistent support over many years, with progress evaluated against clear developmental and technological milestones. This structure means the space program is not vulnerable to the kind of budgetary uncertainty or political turnover common in Western liberal democracies.

Budgetary uncertainty and political turnover indeed.