Moon Monday #216: Firefly Blue Ghost brings precision landing and lunar sci-tech bounties

Plus: Contextualizing the failure of Intuitive Machines’ second Moon mission and that of Lunar Trailblazer as grave losses for NASA.

Last week in lunar exploration was eventful and bittersweet to say the least, with multiple US spacecraft at the Moon. At over 2500 words, this Moon Monday edition unpacks a lot of context on Firefly’s successful CLPS mission as well as on IM-2’s failure for Intuitive Machines and NASA so as to strive to provide you with a true, PR-less sense of the state of US robotic Moon exploration as it stands right now. If you like my compilation, commentary, and analysis, kindly support my independent writing. 🌙

Blue Ghost achieved third most precise robotic planetary landing

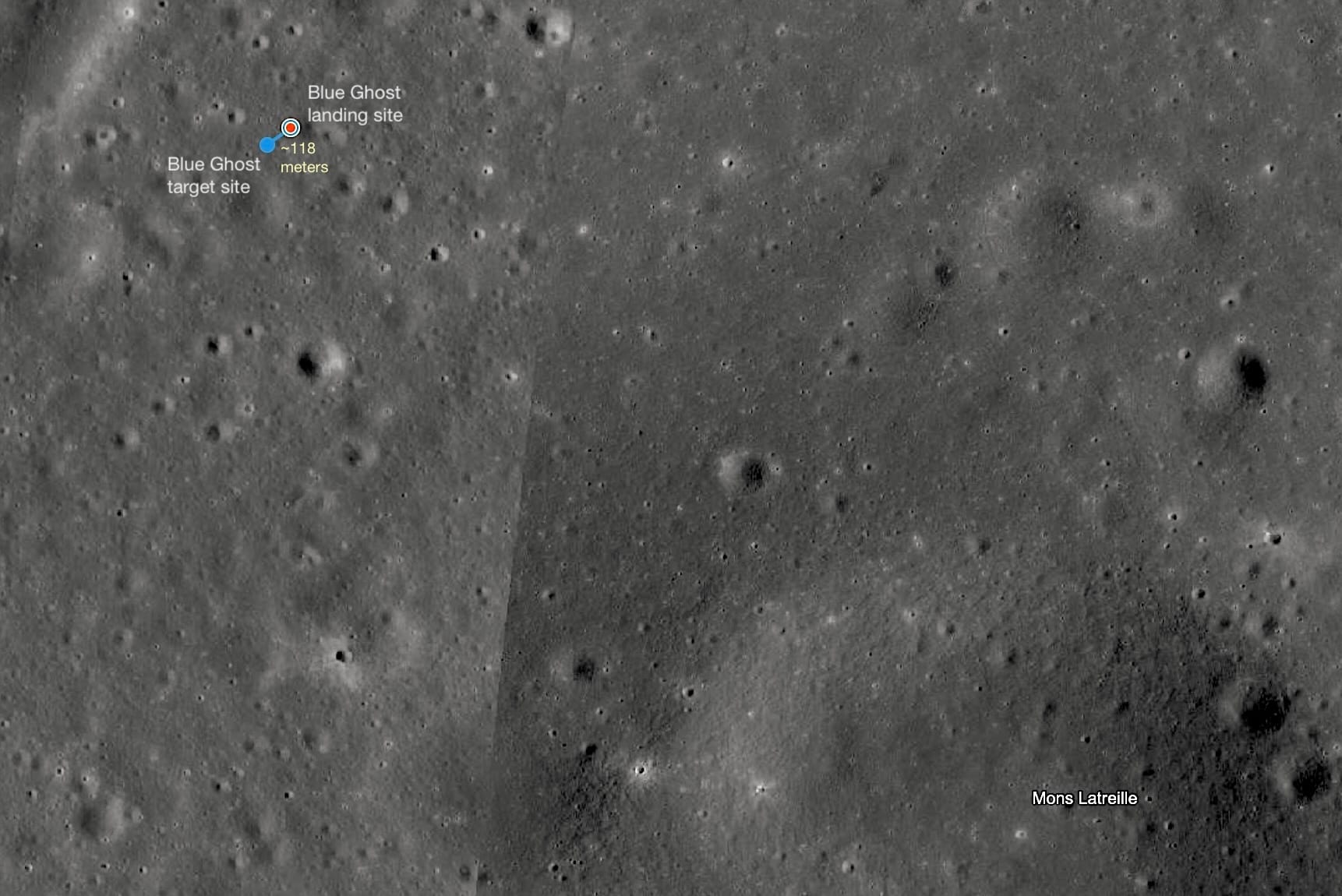

The lunar touchdown of the Blue Ghost spacecraft on March 2, which the US-based Firefly approached and achieved with rigor, not only brought the first soft robotic Moon landing for the US in this century but also elevated the country to the era of precision landings crucial for future space exploration and science. Blue Ghost, part of and funded by NASA’s CLPS program, landed about 118 meters away from its target landing site in Mare Crisium—a remarkably close distance against the vast expanse of our Moon.

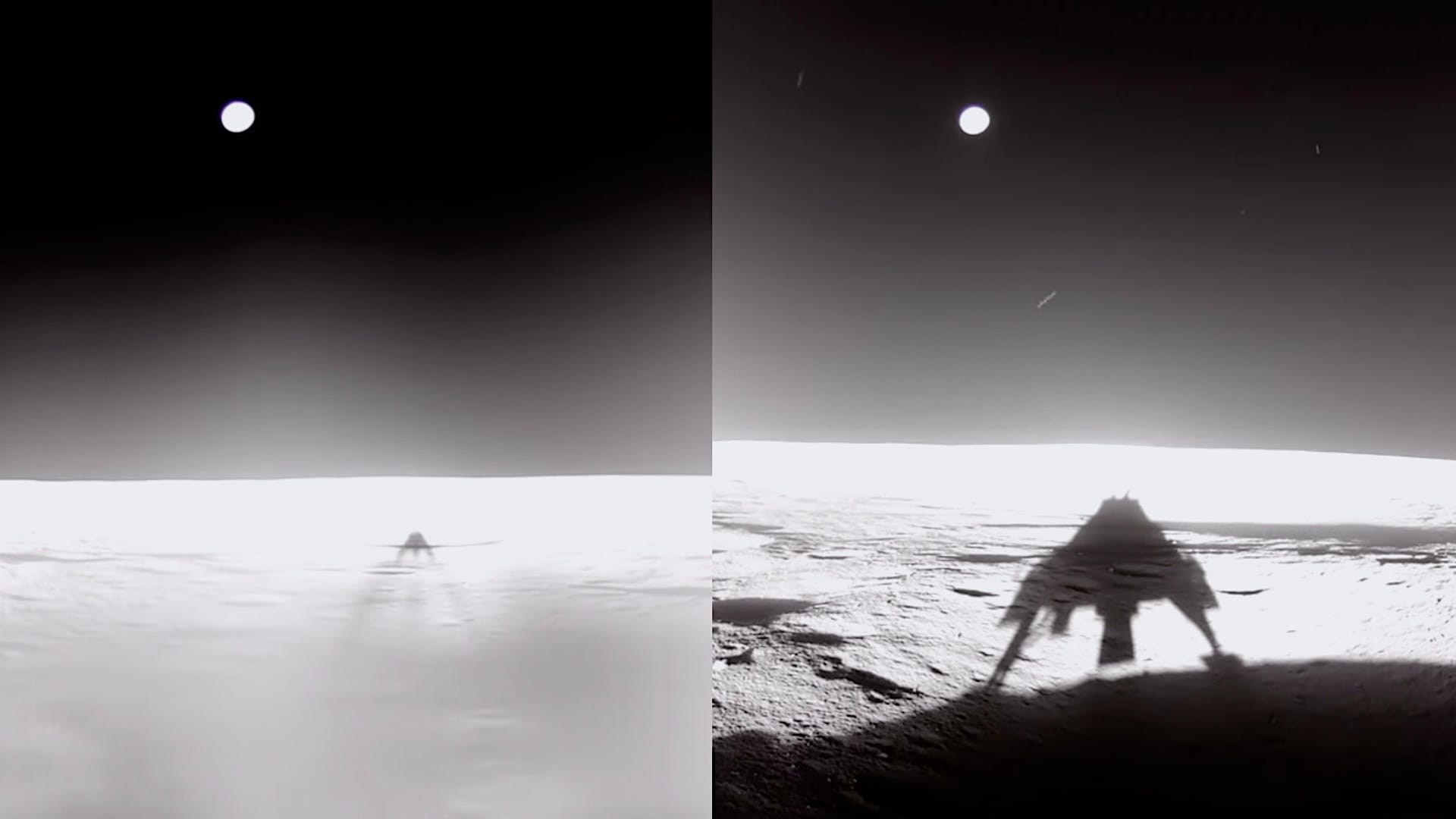

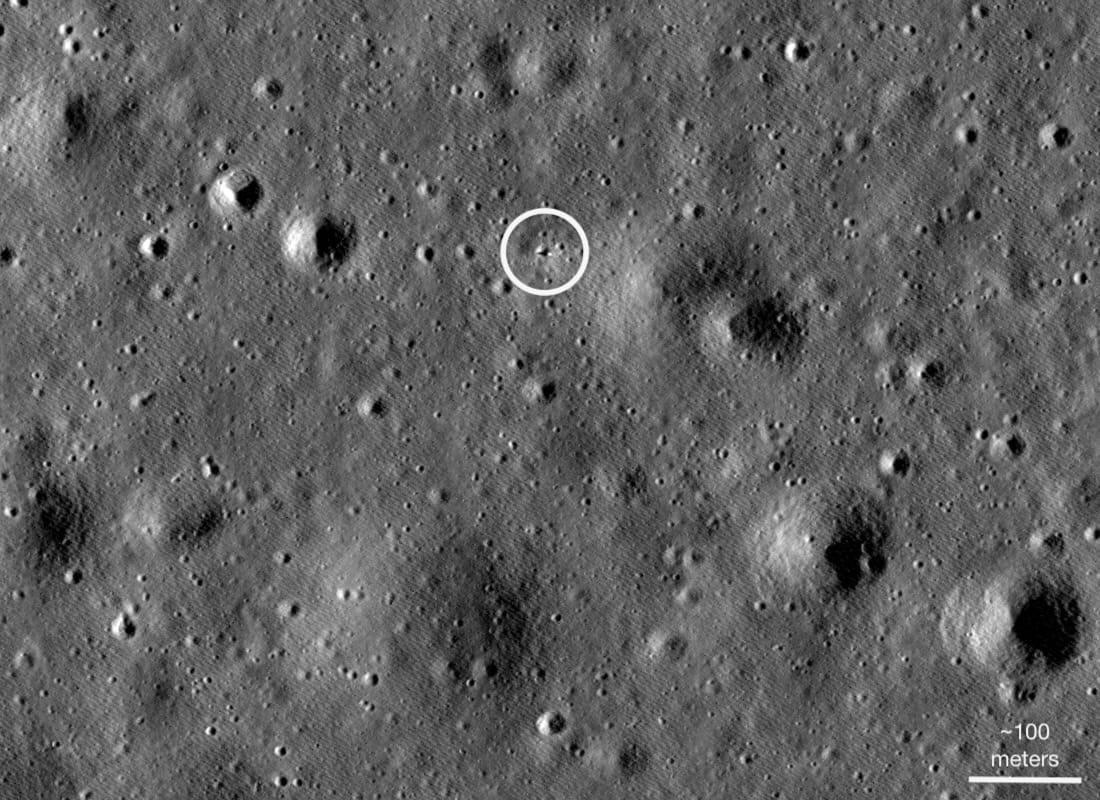

On March 3, NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) imaged the lander from orbit, finding its resting location on the Moon to be 18.5623°N, 61.8103°E. Recall from Blue Ghost’s landing site selection process that its targeted landing spot was 18.560°N, 61.807°E, with a circular “landing ellipse” diameter of just 100 meters. Shortly after landing, Firefly said that Blue Ghost “touched down within its 100-meter landing target.” Assuming the actual targeted coordinates didn’t change by more than 18 meters, and which Firefly hasn’t specified, it does mean that technically Blue Ghost landed a little outside of its landing ellipse. This might be due to the last minute divert maneuver that Blue Ghost made, as can be inferred from its surreal landing video, wherein its hazard avoidance system prioritized a safe spot for touchdown.

In any case, Blue Ghost’s achieved landing precision allows it to be classified squarely in a small but growing global league of lunar landers that are enabling future polar crewed exploration, precision science, and cargo supplies. Blue Ghost proudly follows the lead of JAXA’s SLIM and CNSA’s Chang’e 3 craft, which touched down about 55 meters and 90 meters away from their respective target spots on the Moon.

A busy lunar morning

In the half a lunar day since its local morning landing, Firefly has operated most of the ten NASA payloads onboard Blue Ghost.

- The Electrodynamic Dust Shield (EDS) successfully lifted, repositioned, and removed lunar regolith from glass and thermal radiator surfaces using electrical forces, demonstrating its potential to enable safe, dust-free long-term lunar living for future astronauts.

- Blue Ghost’s ‘Surface Access Arm’ deployed the PlanetVac payload along one of the lander’s legs. Developed by Honeybee Robotics, managed by NASA, and partially funded by The Planetary Society, PlanetVac is a low-cost and efficient soil collection technology which uses pressurized nitrogen gas to suck in samples like a vacuum cleaner instead of bothering with sample-grabbing arms. It did its job. PlanetVac can enable swift, low-cost future sample return missions from the Moon, Mars and other planetary bodies.

- Blue Ghost has also deployed—threw, really!—four tethered Lunar Magnetotelluric Sounder (LMS) electrodes whose data is expected to help scientists learn more about our Moon’s interior, and from it gain better insights on how Luna evolved.

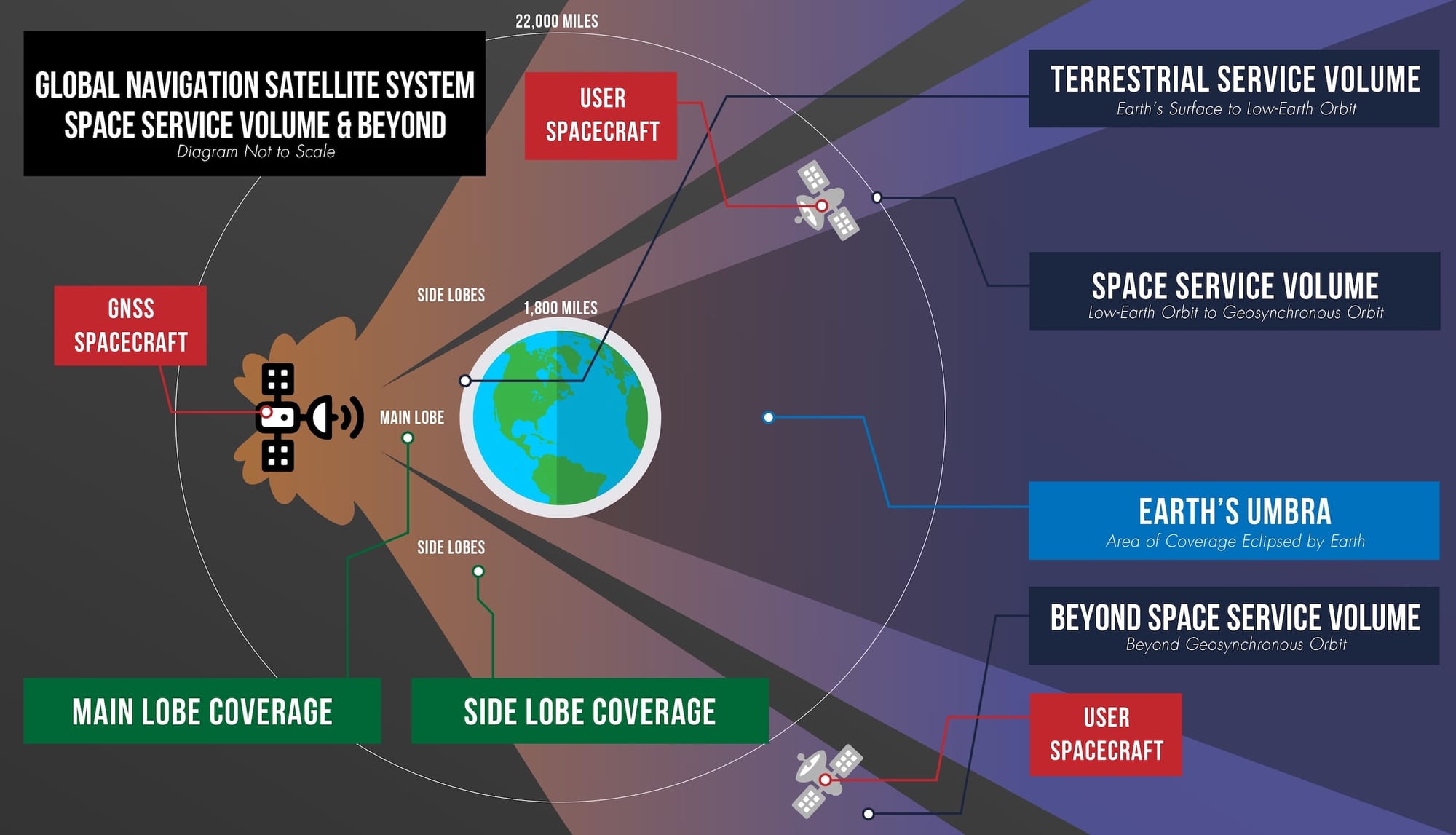

- On March 3, the joint US-Italian LuGRE receiver payload onboard Blue Ghost got navigation signal fixes on the Moon. LuGRE previously achieved GNSS fixes in lunar orbit. It has proved that Earth-based GNSS satellite constellations can help future spacecraft autonomously navigate at Luna without relying on Earth-based tracking. It’s again through the Italian Space Agency (ASI) that we get more details of LuGRE’s surface operations:

Prior to activating LuGRE, the lander underwent a series of system checks to ensure that its onboard systems and scientific instruments were fully operational. A vital step involved calibrating the gimbal, which precisely orients the antennas toward Earth. Only after confirming this alignment could LuGRE be activated to search for GNSS signals. The first GPS G25 signal on L1 and L5 frequencies was received at 7:48 AM, a moment of excitement for the control team, confirming that the receiver had come through landing unscathed and was functioning well. The orientation was confirmed as correct, and operations were as expected. The real breakthrough came shortly after: upon analyzing the initial received data, it was shown that LuGRE locked and traced onto four satellites—two from GPS (G18, G25) and two from the Galileo system (E2, E3). This achievement enabled the first calculation of Position, Velocity, and Time (PVT) fixes on the lunar surface.

Resources to follow Blue Ghost

- Firefly’s Live Updates blog for Blue Ghost

- NASA-funded payloads onboard, amassing nearly 100 kilograms

- NASA’s Artemis blog rather than the inactive official CLPS blog

- Browse my dedicated CLPS coverage webpage and the Moon Monday archive

- My guide on how to follow CLPS updates

- Subscribe for free to Moon Monday to receive mission updates with context 🌝

Many thanks to Open Lunar Foundation, Arun Raghavan and Mia North for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday! If you too appreciate my efforts to bring you this curated community resource for free and without ads, support my independent writing. 🌙

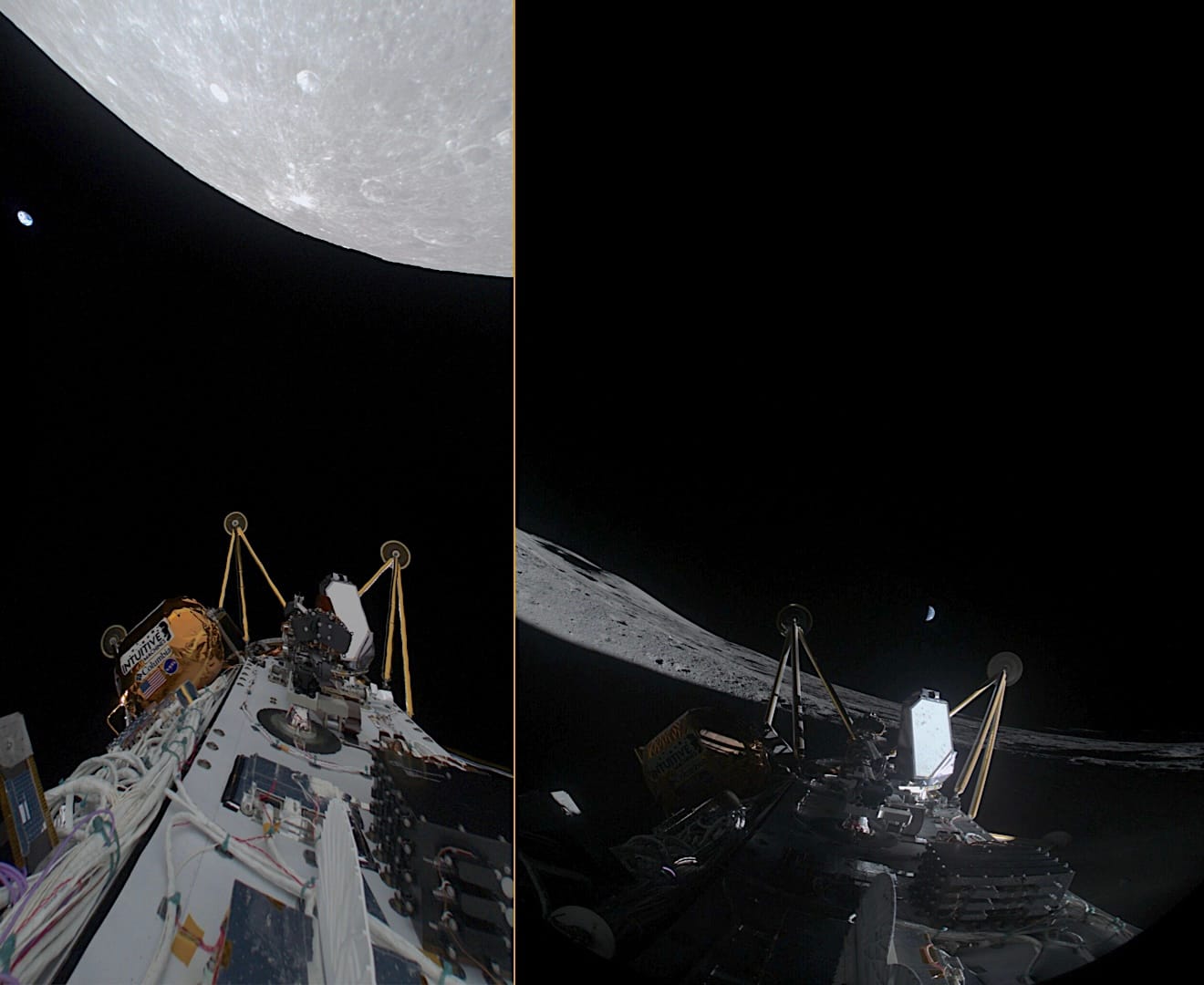

Tipped Intuitive Mooncraft dies with none of the net $130-million worth of payloads deployed

On March 6, Intuitive Machines’ second CLPS lander called Athena landed on the Moon’s south pole around 85°S but ended up resting on its side and inside a cold crater such that it couldn’t generate enough solar power for a single Earth day and died. The lander’s state, including limited communications, prevented any intended operations of the multiple payloads onboard. The mission, called IM-2, has cost NASA $62.4 million for the CLPS flight award, $41.6 million for the Intuitive-built and NASA-funded hopper, and $14.1 million for sending a test 4G/LTE network on the Moon. Non-NASA payloads onboard Athena beared their own development costs and losses, such as the unspecified multi-million dollar rover from US-based Lunar Outpost and Japan-based Dymon’s tiny rover. Following the mission’s end, Intuitive’s shares as a publicly traded company fell by nearly 40% at the end of the week.

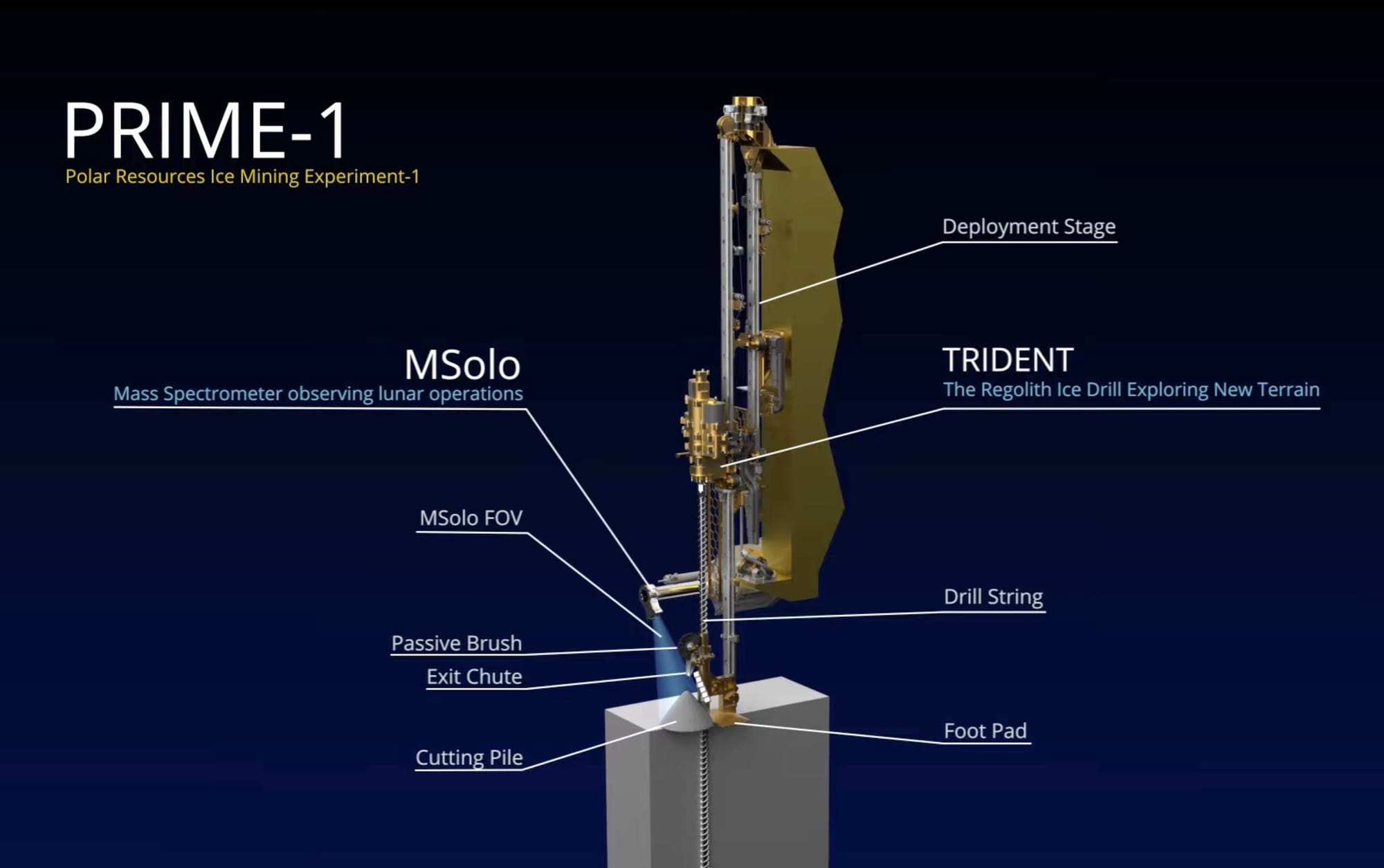

NASA said in a release that the agency-funded, Honeybee-Robotics-developed PRIME-1 drill onboard Athena demonstrated “the hardware’s full range of motion”. Of course, it could not drill the surface as intended because of Athena being sideways. Athena’s MSOLO spectrometer, which was to detect water ice in the drilled samples, ended up only detecting elements likely from gases emitted from the lander’s propulsion system. Recall that the primary goal NASA stated for IM-2’s CLPS contract was to encounter and study water ice. It is thus not met. Other than the rovers by Lunar Outpost and Dymon, the NASA-funded hopper from Intuitive couldn’t be deployed either. The “operations” of all these payloads were limited to commanding them in static modes, primarily proving that their space avionics package worked on the Moon and the structures survived.

Context of IM-2’s failure

Note that IM-2’s landing can be presumed to have been relatively softer compared to the hard-landed IM-1 because it seems that all of Athena’s legs are intact. Crucially, all IM-2 payloads survived to be in a position to operate whereas on IM-1 the aforementioned SCALPPS cameras, for example, couldn’t image landing plume effects due to the anomalously hard landing. That the also sideways and also power-limited IM-1 lander happened to work on the surface for an Earth week while IM-2 lasted less than a day is merely a function of the orientation, attitude, and local topography combinations each lander happened to have, especially due to going in half blind with their laser rangefinders not working in either case.

The laser rangefinders were supposed to be one of the 65 odd improvements Intuitive made for IM-2 with lessons learnt from IM-1. The company even touted its thoroughness pre-landing. On IM-1, the laser rangefinders didn’t work because Intuitive’s engineers forgot to turn off their physical safety switch before launch. On IM-2, it was taken care of along with several tests of the instruments. Per Intuitive, they were “tripled checked” this time. Yet the landed outcome has been essentially the same, made worse for the mission and NASA only by the fact that this was supposed to be a second, informed landing attempt for Intuitive.

However, IM-2’s lander lacked something from IM-1, the NASA LiDAR payload which was developed specifically for precision navigation—as is needed at the Moon’s poles. On IM-1, Intuitive and NASA were prompt to praise the LiDAR for its last-minute role as a mission savior but which actually did not assist the landing in the last 15 kilometers of descent due to delays in processing its data. That was partly because it was a last-day hot patch. However, the NASA LiDAR flying on IM-2 with pre-preparations could’ve offered Athena dissimilar redundancy for its laser rangefinders, which have once again jeopardized the mission.

Given all of the above points, it’s hard to take the positive spin put on IM-2 by the Intuitive Machines CEO Steve Altemus in the post-landing media briefing:

Anytime that you ship a spacecraft to Florida for flight, and end up a week later operating on the Moon, I declare that a success.

Before Athena’s landing attempt, I had hoped that if it does not touchdown nominally, Intuitive would remember what makes a Moon landing “successful” this time around. Unfortunately, I was wrong. It’s also baffling how media outlets like Ars Technica can continue calling IM-1 a soft landing even in their IM-2 coverage.

To NASA’s credit, the agency has been acknowledging IM-2’s outcome upfront, unlike IM-1’s case where NASA disappointingly skewed the success criteria and continued to at various space events and channels when talking of the mission. But for IM-2, Joel Kearns, a leading CLPS executive at NASA HQ, said (emphasis mine):

While we’re disappointed in the outcome of the IM-2 mission, we remain committed to supporting our commercial vendors as they navigate the very difficult task of landing and operating on the Moon.

For NASA, Firefly’s Blue Ghost represents the only objective and nominal success from the four CLPS missions flown thus far. Here’s hoping that the IM-2 review process results in recommendations and implementations that see successful landings and actual scientific operations on Intuitive’s upcoming third and fourth CLPS missions for NASA as well as for the company’s future.

Lunar Trailblazer issues add to the pile of small US spacecraft failing to explore the Moon

The NASA-funded Lunar Trailblazer spacecraft, which launched alongside Athena as a rocket rideshare, is also seeming like a failure. The first set of telemetry from Trailblazer on February 26 indicated that the small spacecraft was facing power issues. NASA lost communications with Trailblazer a day later. Based on ground-based radar data collected on March 2, engineers think that the spacecraft is spinning slowly in a low-power state. Efforts to restore receiving telemetry from the craft and thereafter establishing commanding have failed so far. In the process, Trailblazer has missed performing key trajectory maneuvers necessary to execute the original path plan. As such, Trailblazer will no longer be able to enter its planned lunar orbit, ending the original mission.

The $72 million Lunar Trailblazer was supposed to provide scientists with unprecedented, high-resolution global maps of the amount, distribution, and state of water across our Moon from orbit. It was to also help us better understand several other key scientific aspects of Luna. Trailblazer unfortunately adds to the growing list of NASA-led or NASA-aided small lunar-craft that have failed recently, namely LunaH-Map, Lunar Flashlight, Lunar IceCube and LunIR. :(

More Moon

- In a déjà vu event, SpaceX’s eighth launch of its Starship Super Heavy rocket on March 6 went essentially the same as the seventh one did in January. The eighth flight saw another successful booster stage catch but the upper Starship stage exploded, with its debris showering outside the designated areas and over the Atlantic Ocean and the Bahamas islands. This caused the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) to again divert and delay many flights, and will now lead to the organization conducting yet another Starship flight anomaly investigation. As such, NASA’s long road to putting humans on the Moon with Artemis III, which has been inching through Starship, has slowed down further with this failed flight.

- ispace is targeting June 6–8, 2025 as the landing date(s) for its second Moon lander RESILIENCE, which is currently en-route to Luna via a multi-month, energy-efficient trajectory after launching on January 15 this year. ispace says every single one of its seven major subsystems have been working nominally so far—as are the payloads. The lander will attempt to enter lunar orbit on May 6.

- On March 3, technicians with ESA and Airbus installed the four solar array wings on NASA’s Orion spacecraft in preparation for the crewed Artemis II Moon mission launching next year. Relatedly, NASA is seeking design ideas from creators globally for which plush toy should the agency fly on Orion to act as a zero gravity indicator. A plush Snoopy flew on Artemis I.