Moon Monday #208: What makes a lunar landing mission “successful”?

Before we begin, a note that my thoughts are with everyone affected by the fires in southern California as well as by last week’s 6.8-magnitude earthquake in Xizang, China.

The Moon lander duo from ispace Japan and US-based Firefly Aerospace are being targeted for launch by SpaceX on January 15 as a shared Falcon 9 ride to space. Firefly noted on their Live Updates blog that its Blue Ghost Moon lander has been fueled up and encapsulated in Falcon 9’s fairing as of January 10. Today NASA published a press kit for Firefly’s mission as part of the agency’s CLPS program.

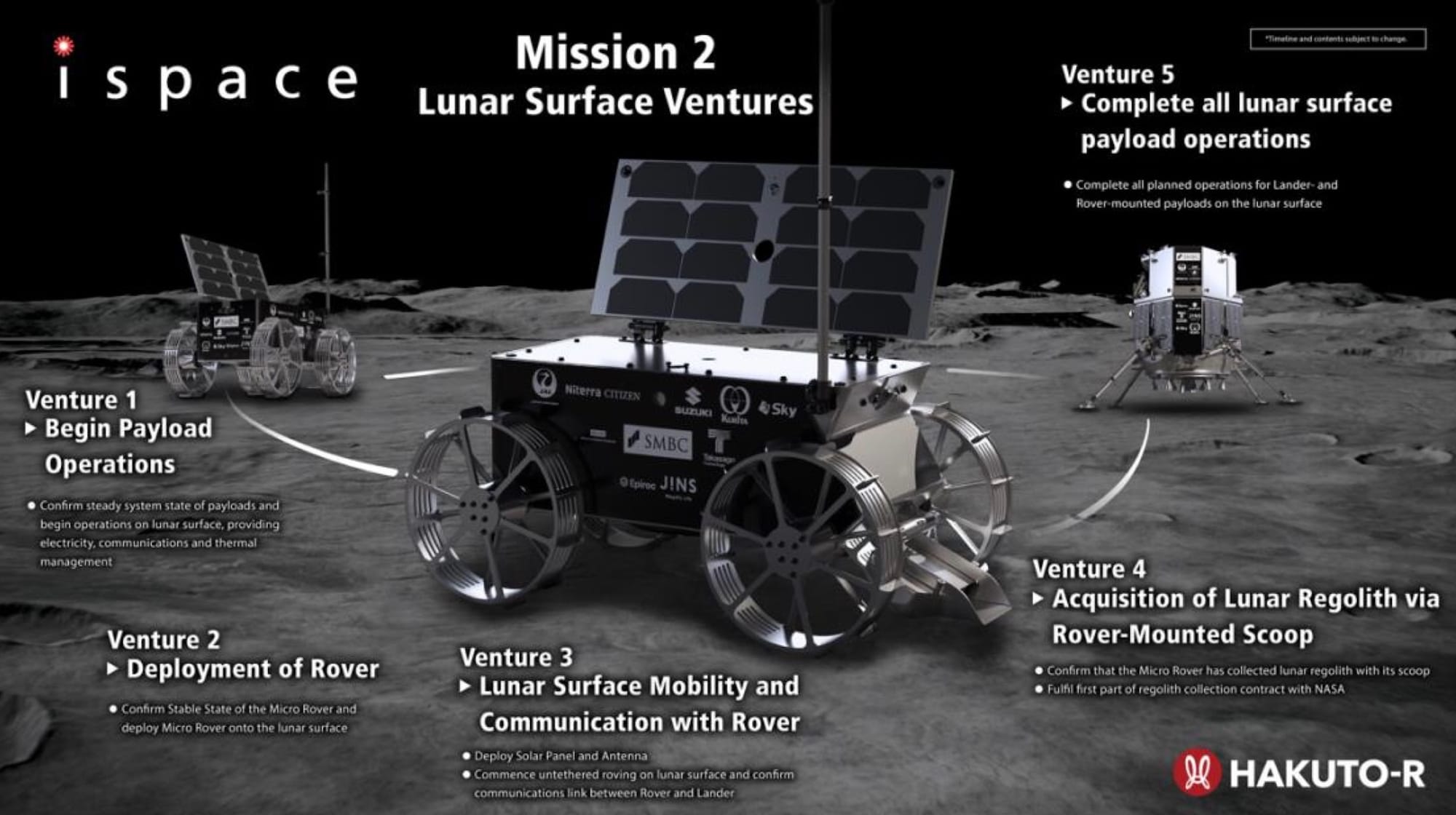

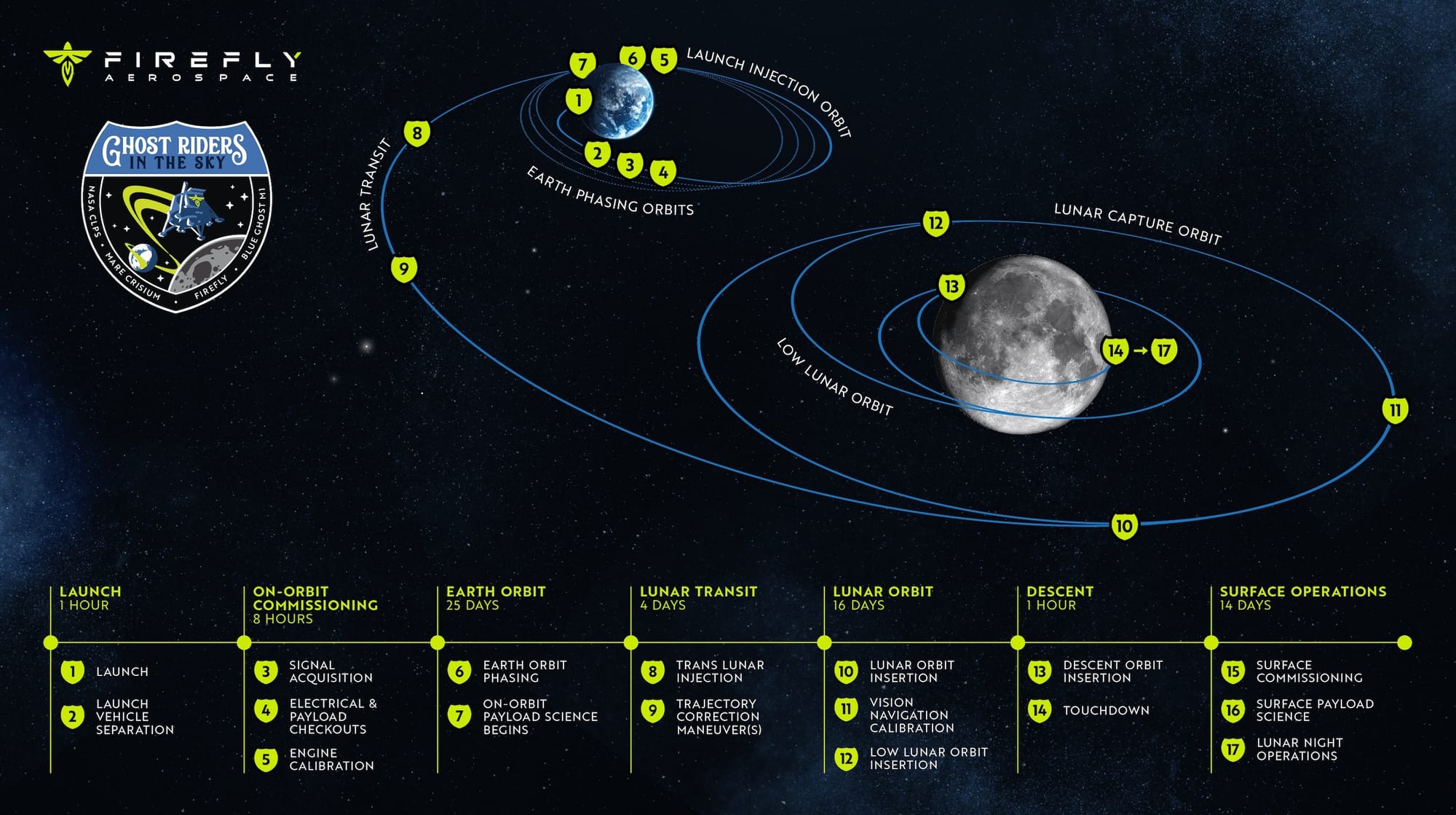

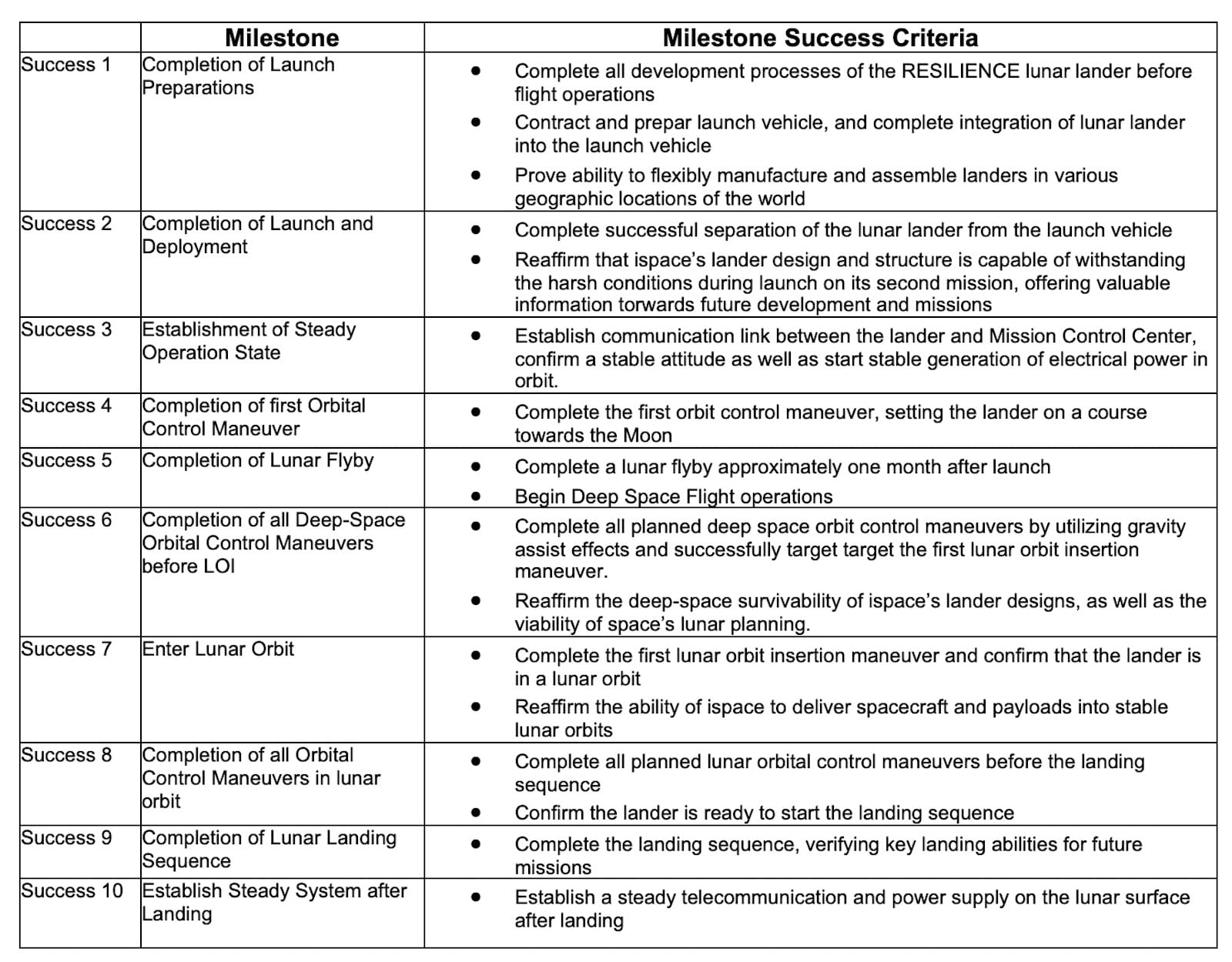

One thing that is notable about both ispace’s and Firefly’s public communications is that they have clearly laid out the milestones and success criteria of their respective missions—(ispace, Firefly)—in terms of specific events.

Note that ispace even went ahead and included a table which lists specific actions or criteria to be met for each of those milestones:

This exercise is something the publicly traded company also did during its first Moon mission. It respectfully stuck to its success criteria despite the outcome of a failed landing. But this wasn’t the case when the Odysseus spacecraft from US-based Intuitive Machines attempted its first Moon landing as part of NASA CLPS, wherein the publicly traded company as well as NASA retrospectively skewed the success criteria for the mission and straight up falsely proclaimed it as a “soft and safe landing” and an “unqualified success”.

Breaking a lander leg does not constitute a soft landing no matter which dictionary you use, an utterly simple fact that most media outlets supposed to keep tax dollars accountable seem to have forgotten. Most of Odysseus’ payloads collecting limited data and one collecting none due to the anomalous landing clearly means the majority of the scientific objectives weren’t met either.

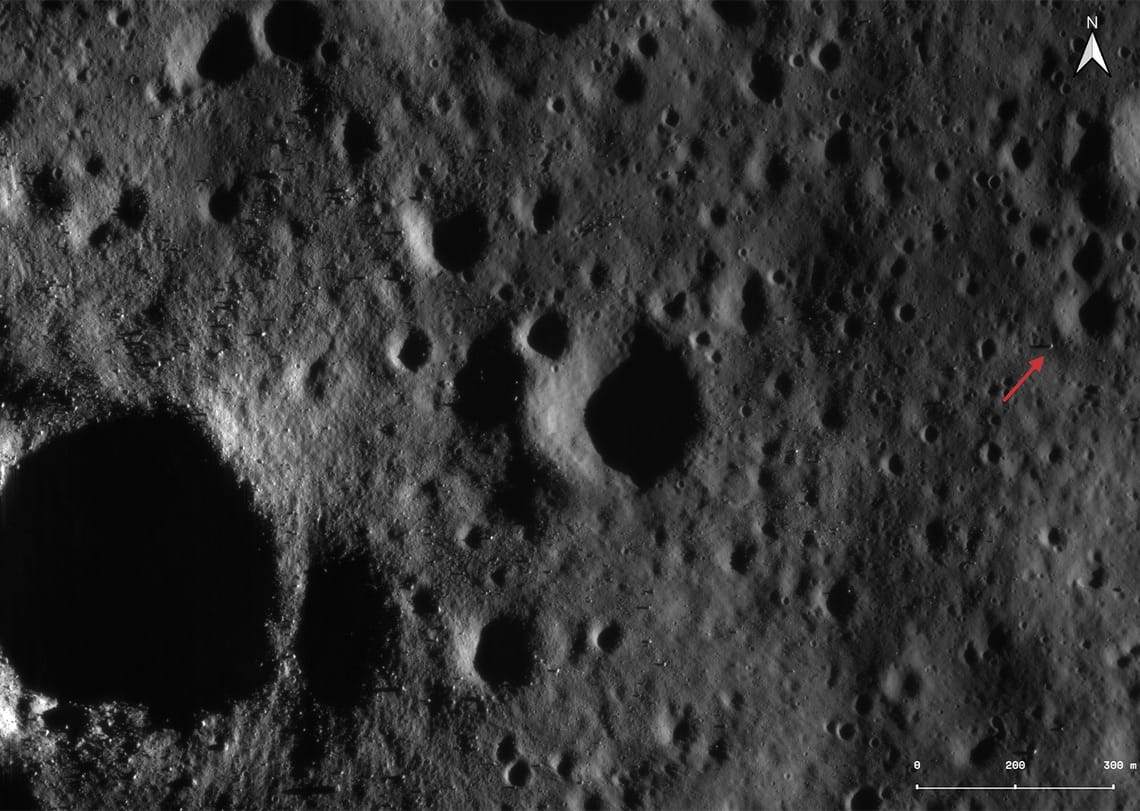

In fact, by all technical measures, the also-hard-landing of JAXA’s SLIM lunar lander was more successful than Odysseus across the board: from the touchdown and the achieved landing precision to payload operations and deployments. SLIM sparked an era of precision landings crucial for future crewed exploration, which includes implications for Artemis through a JAXA-NASA partnership. Despite that, JAXA honored the explicit success criteria for SLIM it had defined pre-launch. Moreover, despite the SLIM lander also having tipped over post its lunar touchdown like Odysseus did, and that it couldn’t even generate power until the Sun circled to the other side over a week later in the future, JAXA nevertheless provided a press update within two hours of the landing which sincerely accepted SLIM’s mixed bag of outcomes.

And yet the western media at large has perpetuated Intuitive Machines’ first Moon landing attempt as being more successful than it really was while not crediting SLIM’s achievements even half as much.

The hard-landing of Intuitive Machines’ Odysseus craft has also been incessantly touted as having created “commercial” success but that too is questionable. As a key example, Jeff Foust noted the following numbers in a November 2024 piece on the search for a commercial lunar economy:

In its 10-Q filing this month, Intuitive Machines noted that its IM-1 lander mission in February, along with its upcoming IM-2 and IM-3 missions—all part of CLPS—are considered “loss contracts” by the company as the cost of executing those missions exceeds the revenue expected from NASA and commercial customers, with $22.8 million in combined losses recorded on them this year alone. Even when working for the government, it can be hard to make money on the Moon.

I wish I could say the issues above are limited to Odysseus. In NASA’s plans to gain lunar navigation and communications (navcom) as a service for its crewed Artemis program, of which Intuitive Machines is a key element as a navcom provider, the agency has been opaque in publicly communicating its contract values and related specifics. This has also notably been the case for NASA transferring operations of two of its key lunar orbital imagers to Intuitive Machines.

These traits should be concerning for the US space communities, who often are the first ones to call out other countries for lack of transparency.

Don’t get me wrong. Even in my piece critiquing the Odysseus mission’s public communications, I’ve admired the technical feats Intuitive objectively achieved, including Odysseus being the first to lunar land using cryogenic methalox engines and remarkably making it to Luna alive using only optical navigation and an IMU. I’ve also been covering Intuitive’s upcoming second and third Moon landing missions contracted by NASA under CLPS, the latter’s science, their recently contracted fourth CLPS mission, and several other related developments for years. I even helped make a video on their upcoming missions!

But that does not mean I will celebrate Intuitive’s first Moon landing as being more successful than it really was—even if it has been normalized now. Just like how ISRO retrospectively calling the Chandrayaan 2 mission a “98% success” despite the crashed lander does not make it so, Intuitive and NASA redefining the mission doesn’t change the past. It’s my duty to share this with my readers.

Another reason to raise the issue is that I have grown up being immensely inspired by NASA. I hold great admiration for many pioneering aspects of the agency. I’m often found urging ISRO officials to follow NASA’s long-standing example in communicating the science and technology aspects of civil space missions. But I don’t believe this recent facet of NASA vis-à-vis Artemis is healthy in the long run, especially when the US aims to be the country leading sustainable exploration at the Moon.

If we truly want sustainable lunar exploration, we also need to be true to ourselves. Do we desire our Moonbase to be built on a house of cards or cemented concrete?

And so I hope that with ispace’s and Firefly+NASA’s upcoming Moon landing missions, the organizations will follow the honorable example of ispace’s own past communications in the event of a landing failure, or leave a trail of transparency like Astrobotic did when its ailing lander precluded a lunar descent attempt altogether. Likewise, in the case of success, I hope they choose the outlook of SLIM’s humble embrace. To me, this is what makes a Moon mission successful other than the obviously needed technical execution. We carry both these choices into the future.

On that note, I’d like to remind you—my dear readers—that as stated in my public Editorial Independence Policy, I do not own shares of any space company, primarily to keep my writings unbiased. It doesn’t matter if the company is publicly listed like Intuitive Machines or ispace Japan, or if it offers private stock like many others in the industry. I own none of it. As such, any enthusiasm, neutrality, or criticism expressed in my coverage of lunar and space developments is intended to be genuine. I wish all publishers, writers, and creators in the space industry revealed beforehand if they have any such vested interests. How else can we know whose piece of praise to trust?

I have exactly nothing to gain financially from private lunar companies whether they go public or commercial. My Moon Monday blog+newsletter is sustained purely through organization sponsorships and individual reader donations. And so if you like my work aimed at a better future on our Moon for people worldwide, support my writing.

Artemis updates

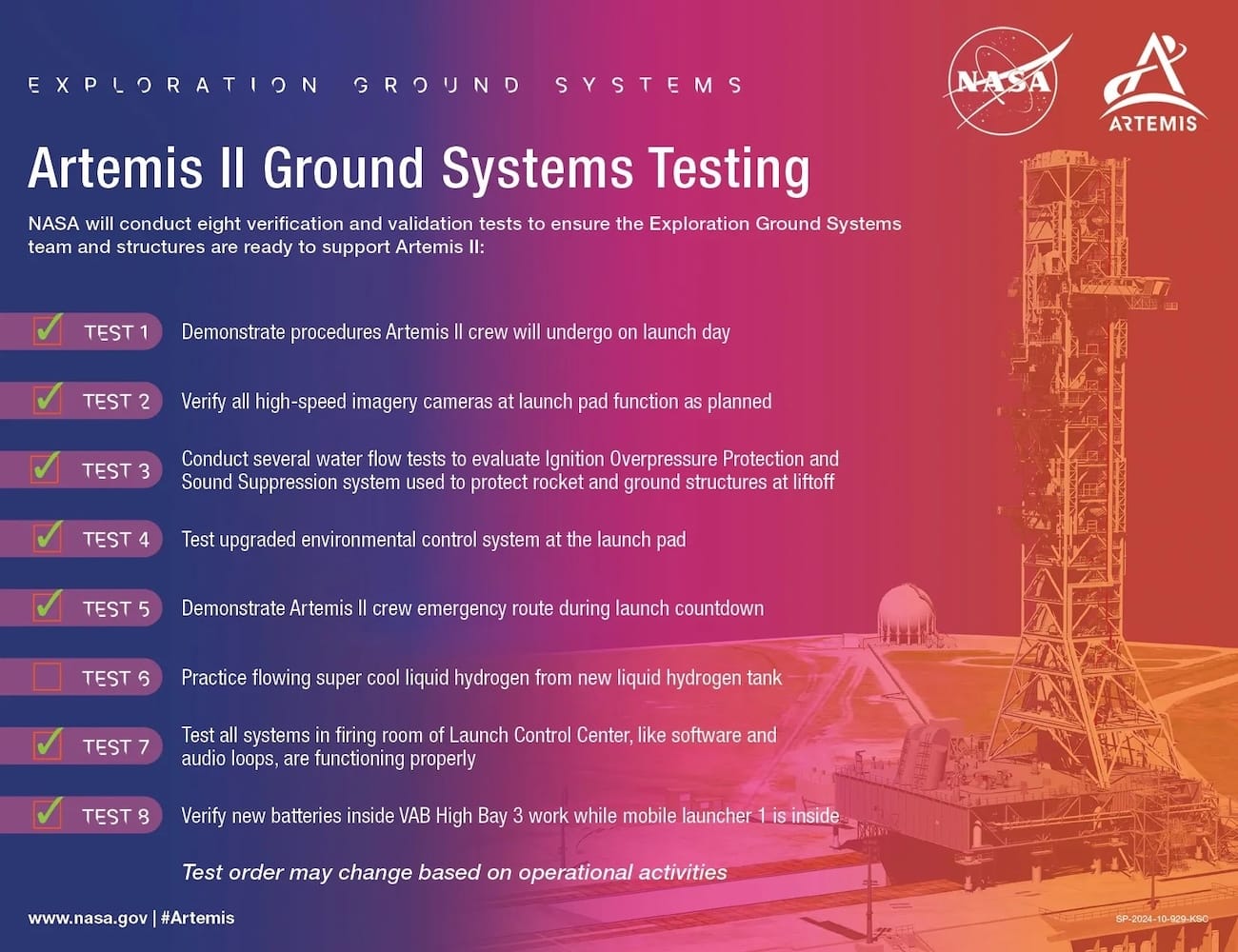

- As the seventh test in a series of eight ahead of the eventual second launch of the SLS rocket in 2026, ground teams successfully tested that the rocket and its associated infrastructure will receive uninterrupted power supply around liftoff. The second SLS launch will push four astronauts in an Orion spacecraft towards the Moon on the Artemis II mission. For the final high-level test in preparing ground systems for the SLS launch, teams will practice flowing cryogenic liquid hydrogen from a new tank at the launch complex.

- NASA continues testing aspects of the Artemis I Orion spacecraft, which returned to Earth after its mission, to better characterize and fine-tune the spacecraft’s configuration for future missions with crew.

- To ensure tackling the challenging lighting conditions under which Artemis astronauts will operate on the Moon’s south pole, NASA is revisiting the requirements for achieving safe and functional vision for astronauts:

Tasks expected of astronauts were not incorporated into system design requirements to enable system development that ensures functional vision in the expected lighting environment. Consequently, the spacesuit, for example, has flexibility requirements for allowing the astronauts to walk but not for ensuring they can see well enough to walk from brilliant Sun into a dark shadow and back without the risk of tripping or falling. Importantly, gaps were identified in allocation of requirements across programs to ensure that the role of the various programs is for each to understand functional vision. NESC recommendations were offered that made enabling functional vision in the harsh lighting environment a specific and new requirement for the system designers. The recommendations also included that lighting, window, and visor designs be integrated.

Many thanks to Open Lunar Foundation, Henry Throop, Gurbir Singh and Abhinav Yadav for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday!

If you too appreciate my efforts to publish this curated community resource for free, support my independent writing. 🌙

More Moon

- Intuitive Machines is preparing parts of the Athena lander for its second CLPS Moon landing mission with a target launch no earlier than late February on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

- Shooting micro-spectrometers into the lunar soil could be a cool way to measure composition across a geological area or region of interest instead of having to walk or rove to each location within, Andy Tomaswick reported.

- Open Lunar Foundation is hiring for leadership and operations roles.