Moon Monday #150: On China’s Queqiao 2 lunar mission, India’s Moonbound human spaceflight ambition, and more

Today marks 150 weekly editions of archiving and contextualizing global developments in the exploration of our Moon. It’s satiating to work on and write the world’s only such resource. If you enjoy and appreciate my work to serve space communities worldwide, kindly consider sponsoring Moon Monday as an organization or individual to help sustain and flourish my flagship writing. 🌙

For this 150th Moon Monday, I happen to have quite a lot to unpack so let’s get started!

China to launch the ambitious Queqiao 2 lunar orbiter in early 2024

CNSA is on track to launch the 1200-kilogram Queqiao 2 lunar orbiter in March next year on a Long March 8 rocket, Andrew Jones reports. Its 4.2-meter wide parabolic antenna will relay communications between Earth and at least three of China’s upcoming Moon landers: Chang’e 6 launching in 2024, Chang’e 7 launching in 2026, and Chang’e 8 launching in 2028.

Unlike the first Queqiao relay satellite, which is halo-orbiting the second Earth-Moon Lagrangian point to serve the farside Chang’e 4 mission, Queqiao 2 will be in an inclined elliptical orbit that spends most of its time looking over the Moon’s south pole. CNSA expects that because this kind of a stable orbit requires less fuel to stay on course, Queqiao 2 will serve missions for more than eight years. To that end, China will offer the satellite’s communications relay services to other countries and organizations sending Moon missions.

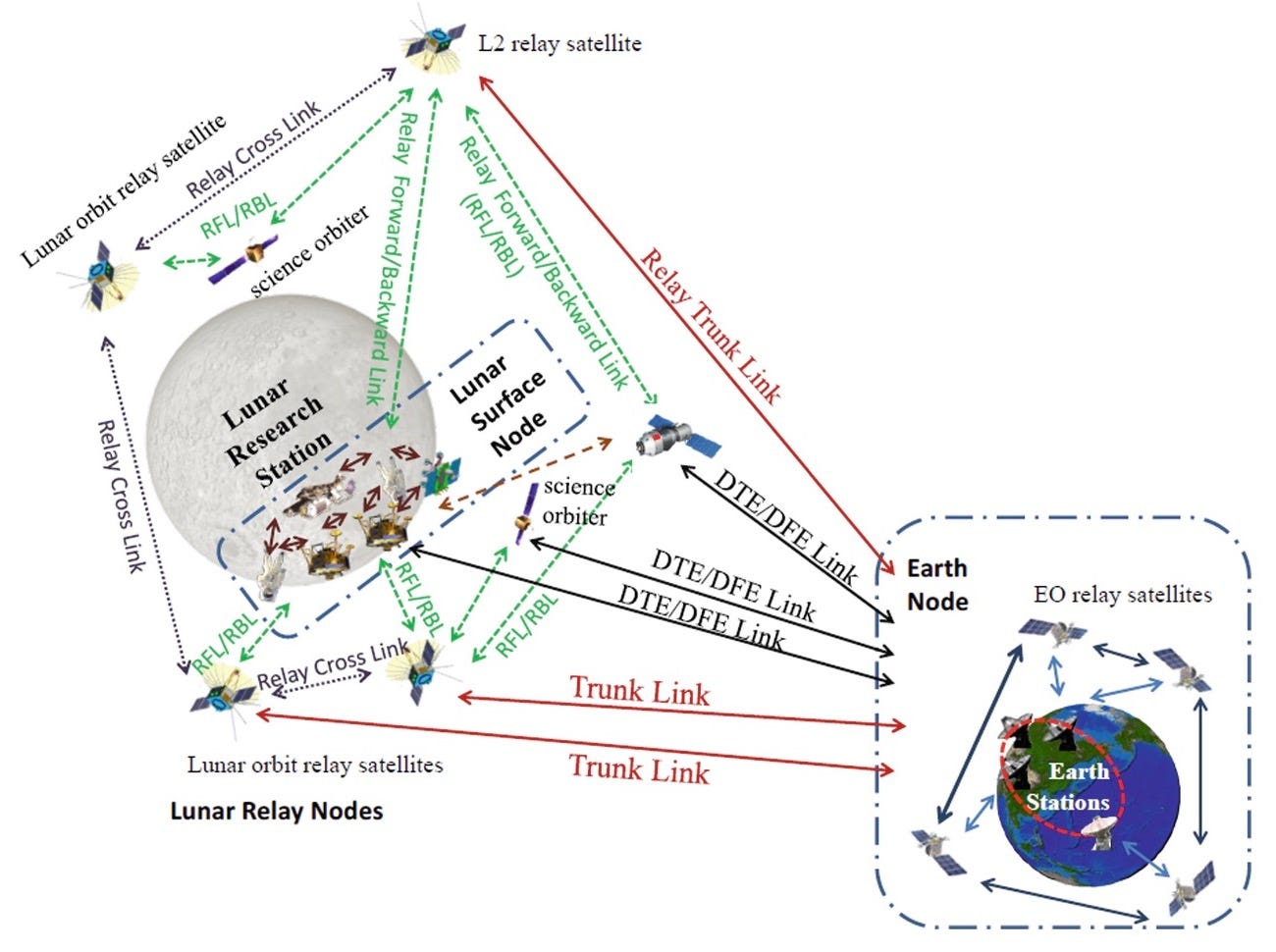

In fact, Queqiao 2 will be part of China’s larger satellite constellation providing navigation and communications (NavCom) for hardware and crew on and around the Moon as part of China’s upcoming long-term scientific Moonbase called the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS). Relatedly, Queqiao 2 will deploy two experimental Tiandu CubeSats to test lunar communications and navigation payloads.

Also related is ESA’s Moonlight initiative, which too aims to provide a NavCom lunar service starting with the launch of UK’s Lunar Pathfinder orbiter in 2026. ESA will be the anchor customer of Moonlight but expects companies to actively commercially provide NavCom services to customers globally. To that end, ESA is providing up to €200,000 per study to entities proposing viable lunar business concepts and applications that would benefit from or be enabled by Moonlight. In the meanwhile, Lockheed Martin’s new subsidiary Crescent Space is targeting a 2025 launch of its first two NavCom satellites. More potential competitors in this space include ArkEdge Space, Aquarian Space, and Plus Ultra.

India wants to send a human to the Moon by 2040, and how the Gateway presents a promising path

On October 17, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi directed ISRO to send the first Indian to the Moon by 2040. To realize this ambition, the Indian Department of Space (DOS) will develop a roadmap for lunar exploration, which will comprise a series of Chandrayaan missions, the development of a partially reusable Next Generation Launch Vehicle (NGLV), a new launch pad, and more.

The first of this “series of Chandrayaan missions” will be the joint ISRO-JAXA mission LUPEX. Launching before end of decade, LUPEX comprises an ISRO-developed ~6000-kilogram lander which will deliver a JAXA-built ~350-kilogram rover to directly study the nature, abundance, and accessibility of water ice at the Moon’s south pole. The Japanese government has approved the LUPEX mission but India is yet to, and so that’s the green light to look out for soon. LUPEX and its successors will provide ISRO with crucial data to plan crewed lunar surface missions.

Of course, India is a long way away from realizing the trove of technologies needed to plan the feat of an indigenous human Moon landing. The country’s biggest near-term goal is to send humans to Earth orbit first with the Gaganyaan mission mid-decade. ISRO recognizes the sheer scope of its Moonbound undertaking, and that’s why the date to send an Indian to Luna reads “by 2040”—realistic yet aspirational. Note though that the associated press release only specifies sending the first Indian “to the Moon” by 2040. It doesn’t tell if Indians will land on the Moon or be sent to lunar orbit. The latter is definitely achievable by 2040, and is also where India’s recent signing of the US-led Artemis Accords offers a gateway—literally.

ISRO Chief S. Somanath said in a March 2023 interview—before India signed the Accords—that the agency is considering contributing to the Gateway, an upcoming NASA-led international lunar orbital station for Artemis astronauts. And so similar to how NASA is providing crew seats to Japan, Europe, and Canada in return for their respective contributions to the Gateway, India can grab one as well.

This isn’t to say India won’t eventually send humans to the Moon by itself anyway but that the Gateway presents the path of least resistance. Being an Accords signee will only be of aid to India here, especially when considering that the associated factsheet from the recent India-US agreements signals a wide scope for human spaceflight cooperation between the two countries:

NASA will provide advanced training to ISRO astronauts with the goal of launching a joint effort to the International Space Station in 2024. Additionally, NASA and the ISRO are developing a strategic framework for human spaceflight cooperation by the end of 2023.

Hopefully ISRO gets the much needed substantial budget increases starting next year to back up and reinforce these newfound ambitions.

Many thanks to Epsilon3, Parvathy Prem and Planetary Scientist David Blewett for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday.

Pakistan joins China’s long-term lunar exploration project, and how not to interpret it

As Pakistan prepares to have its first lunar orbiter called ICUBE-Q launch aboard China’s Chang’e 6 mission in 2024, the country has officially joined the aforementioned ILRS project. Andrew Jones notes that ICUBE-Q is a CubeSat being developed with help from China’s Shanghai Jiaotong University.

Considering the political ties between China and Pakistan, and the latter’s history of leaning into China for space development, it’s not surprising that Pakistan joined the ILRS. But what is surprising is the article by Eric Berger—on the popular western publication Ars Technica—equating the development to somehow increased chances for NASA’s return to the Moon with humans under Artemis. The article’s title is “Why NASA’s return to the Moon will likely succeed this time”, and it asserts the following as a key argument:

But more broadly, the 29 signatories to the Artemis Accords have indicated they want to partner with the United States as it goes back into deep space, to the Moon, and possibly beyond. Among the most notable participants, from a geopolitical standpoint, is India, which signed on this summer.

The strategic overtones of the return to the Moon were emphasized on Friday when China announced the newest partner for its project to build a lunar research station on the south sole of the Moon: Pakistan.

[…]

Pakistan is a notable addition because of its historic rivalry with India—this may push India to align itself even further with NASA and the Artemis program. That would be a good thing for both countries, as India has a growing and ambitious space program.

As an Indian with at least a basic understanding of the relations between India, Pakistan, and China, I find Eric’s assertion baffling. I don’t intend to dunk on my fellow space friends in Pakistan but ISRO and related Indian authorities in the associated geopolitical decision making chain are not concerned about Pakistan’s civil space activities. India didn’t take its decision to sign the Accords based on what Pakistan’s stance might be. Just one look at the wide gap in space capabilities between the two countries should be enough to dismiss such assertions. Moreover, India and China don’t have good relations to begin with.

Yes, space is political, and its undertones do permeate terrestrial matters, but it does not mean that every single decision and activity is driven by politics alone. And every event certainly doesn’t fall, or need to, on the US-China plane of thought. I felt compelled to highlight this on Moon Monday because such pieces, which seem to never end, cause unnecessary friction and divides.

Mission updates

- In a talk at TIFR Mumbai, Santosh Vadawale from the Chandrayaan 3 rover team said that a test, low-wattage radioisotope heater unit (RHU) is aboard the Chandrayaan 3 propulsion module, which is in lunar orbit right now! ISRO hasn’t formally announced the RHU’s presence. The Indian space agency’s foray into operational RHUs is a great sign as it’s precisely the technology that enables hardware like the Chang’e 4 lander and rover to wake up after frigid lunar nights. The lack of a heating mechanism on the Chandrayaan 3 lander and rover is what restricted their mission to one lunar day or 14 Earth days. ISRO’s future Moon mission designs might now find an RHU option at their disposal.

- On October 17, NASA conducted the first of 12 hot fire tests of the fully redesigned RS-25 engine to be used on future SLS rocket Moon flights. After this final test series, which follows from the first one in June, new RS-25 engines can be produced for Artemis V and beyond. Both series of tests include eight 500-second firings—the same amount of time as required during an SLS mission—and four longer burns for ensuring margins. Engineers and operators also test flight-like gimbaling of the engine, which during a mission helps stabilize the rocket as well as keep it on its intended trajectory. Like the engine on the first test series, the second series one also features new components like a nozzle, hydraulic actuators, flex ducts, and turbo pumps. The aim here is to test production reliability by validating the performance of a second hardware set.

- On October 20, ispace Japan announced being awarded a $80 million government grant to develop and launch a large lunar lander by 2027. It will carry more than 100 kilograms of payload to the Moon’s surface as opposed to the 30-kilogram capacity of the Series 1 lander, which flew on the company’s Mission 1. More details are unclear at the moment but ispace calls the new lander design Series 3, which based on its mass class and provided descriptions seems similar to or borrowing from the Series 2 / APEX lander being developed by ispace US for an upcoming NASA CLPS mission via partner Draper.

More Moon

- With the aptly named PAVER project, ESA is testing a process which uses powerful lasers to melt lunar soil simulant into glassy solid surfaces to create blocks of roads and landing pads on the Moon. Relatedly, Kevin Cannon recently elaborated in a paper that just like on Earth, not all lunar soil is suitable for construction.

- Space Crew has listed more than two dozen job openings related to lunar exploration, from companies like Blue Origin and Lunar Outpost.

- What were some challenges and best practices in covering ISRO’s Chandrayaan 3 Moon landing? I’ll be part of an hour-long panel tomorrow discussing that at a global multilingual conference on science journalism. The event is paid (I don’t get anything) but I’ll share the video later if possible.