Moon Monday #186: VIPER’s CLPS conundrum, ispace’s rover, and more

Going deeper into VIPER

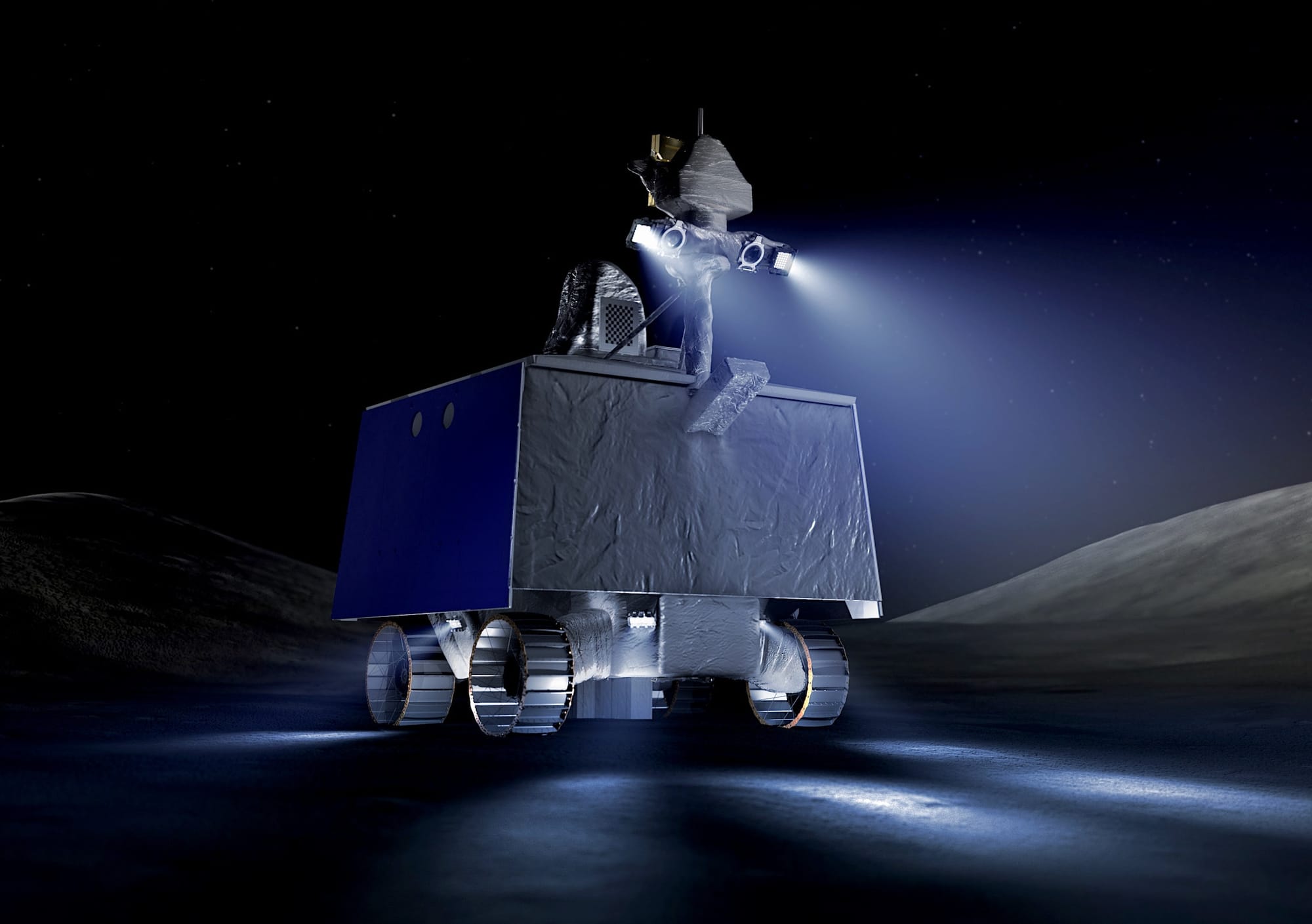

Much has been said about NASA’s July 17 announcement to cancel the VIPER rover supposed to fly to the Moon’s south pole on Astrobotic’s Griffin lander mid-decade as part of the agency’s CLPS program to uniquely explore water ice there. Instead of duplicating arguments about continually rising cost and launch delays, I thought it might be informative to add questions and thoughts on more things related to or affected by VIPER.

What happened to NASA-tasked tests for VIPER’s lander?

Owing to VIPER’s vitality to helping NASA plan future crewed Artemis missions to the Moon’s poles, the agency took a more conservative approach for VIPER’s delivery compared to any other mission in the CLPS program. In 2022, NASA awarded Astrobotic an additional $67.8 million atop the original $199.5 million contract to perform three propulsion system tests of Griffin to reduce risks of a landing failure. This would delay VIPER’s launch by a year to November 2024 but one NASA was willing to accept in part because the rover itself would need time to be fully built after facing supply chain delays from the pandemic.

Neither NASA nor Astrobotic have shared results of these tests with the public, which is all the more concerning since Astrobotic’s first lunar lander Peregrine failed shortly after its launch in January due to a propulsion system issue. In fact, a recent report on CLPS published by NASA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG) reveals that Astrobotic hadn’t adequately flight-qualified Peregrine’s main engine prior to launch, and how the issue could cascade to Griffin:

Both Astrobotic’s Peregrine and Griffin landers use the same engine and tank subcontractors with a scaled up TALOS axial engine for Griffin. Due to engine delivery delays and testing performance issues, the Peregrine TALOS axial engines were never subjected to qualification levels or fired for full duration prior to its flight.

To better gauge all risks associated with Griffin being able to safely deliver VIPER to the Moon, the OIG CLPS report states that NASA had modified VIPER’s delivery contract to get “augmented insight” into the mission’s development:

Augmented insight allowed NASA to assign a full-time resident CLIM [CLPS Integration Manager] at the vendor’s [Astrobotic] facility to improve communication between NASA and the vendor. In addition, the vendor is now required to provide monthly status reports on the development of its Griffin lander and support three new Independent Assessment Team reviews. These reviews will be held approximately 2 years, 1 year, and 1 month prior to NASA handing over VIPER to Astrobotic for launch. According to CLPS management, this augmented insight gives NASA a greater understanding of the risk environment and the VIPER mission’s risk exposure.

Furthermore, consider that Peregrine’s mission ended well before its lunar descent could even begin. As such, Astrobotic unfortunately couldn’t get any data from this critical phase to know how well the lander’s guidance, navigation, and control systems would’ve performed against engineered expectations. Such information would’ve certainly enhanced Griffin’s ability to nail VIPER’s landing amid the treacherously rocky terrain at the lunar south pole.

And so, what if the combined results of Griffin’s propulsion tests, NASA’s augmented insight into the mission, and Peregrine reviews did not provide enough confidence to NASA about Griffin’s ability to deliver VIPER safe and sound? If so, NASA’s decision may not be about saving additional costs to be spent on VIPER or approaching the US Congress for extra funds as much as it could be about expecting that the mission lander might not be up to the task after all, and in which case more testing would mount costs on that end too.

Has VIPER affected other CLPS missions?

According to the aforementioned OIG CLPS report, “one NASA SMD [Science Mission Directorate] official stated that the Agency has removed at least one future CLPS mission to help pay for and ensure the success of VIPER.” Relatedly, recall that it’s been over a year since NASA was supposed to announce which CLPS vendor is being awarded a payload suite delivery to one of the (formerly-)volcanic Gruithuisen Domes on the Moon in 2026. Given the lack of such an announcement, two more CLPS missions supposed to follow the flight to Gruithuisen—one to the lunar south pole and one to mysterious Ina—have subsequently seen little progress as well.

In the announcement and follow-on briefings about NASA’s intention to cancel VIPER, the agency stated growing mission costs risking overstepping into budgets meant for other CLPS missions. Considering that NASA’s quoted cost to continue VIPER while accommodating launch delays is at least $50 million a year, which is approximately half the actual average cost of all other CLPS delivery contracts, it’s plausible to think the agency chose to be able to fly at least one additional CLPS mission instead of prioritizing VIPER. As Casey Dreier of The Planetary Society notes:

From the perspective of NASA’s science leadership, however, finding $51 million in the existing budget presents some impossible choices. Within LDEP [the Lunar Discovery and Exploration Program—VIPER’s budgetary home], the only significant sources of funding available for VIPER would be to reduce the politically popular CLPS program, cut funding to scientific instrument development for CLPS missions, or cut funds for science instrumentation for upcoming Artemis missions. None of these were deemed acceptable tradeoffs.

Additionally, Michael Greshko notes for Scientific American how the larger NASA budget constraints are acting in the background:

In a draft NASA budget released on July 9, the House of Representatives’s Committee on Appropriations recommended giving between $458 million and $533 million to the NASA program that houses VIPER—up to $75 million more than the Biden administration had asked for. While this language would give NASA some flexibility to boost VIPER’s funding, it also creates a zero-sum game because Congress hasn’t signaled that it will raise NASA’s overall science budget.

This drives home the point the Orbital Index (a Moon Monday sponsor) made about the US Congress micromanaging NASA spending:

Much of the issue is also appropriations micromanagement from Congress, with the broken legislative environment in the US leading to congressionally-mandated spending on unsustainable ‘jobs’ programs like SLS.

As such, with NASA’s exploration and technology development funding—especially from the SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft—not being transferrable to VIPER in any way, NASA chose to kill it in favor of more CLPS flights, hoping to convince the US Congress to fund a CLPS 2.0 for another decade. NASA sacrificing VIPER to save CLPS is rather ironic though since, as Eric Berger reported previously, NASA had briefly considered a traditional delivery for VIPER considering its importance for Artemis. But the higher costs and timelines for VIPER bypassing CLPS would’ve effectively killed the CLPS program, which NASA SMD as CLPS’ managing body wouldn’t accept.

Are VIPER’s launch delay costs really that high?

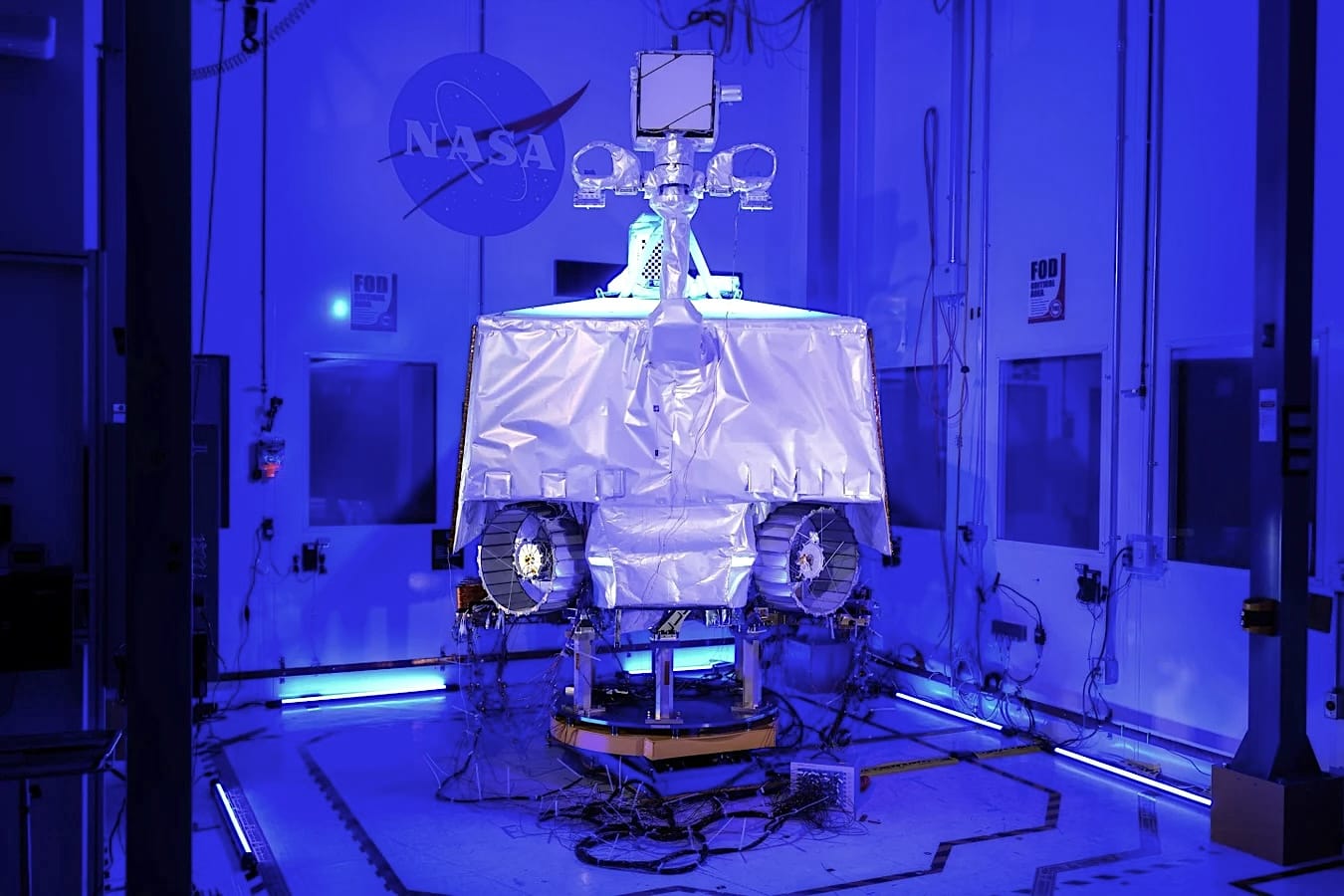

It seems NASA did not provide the VIPER team an opportunity to propose cost-saving measures prior to announcing the intent to cancel the mission. As Marcia Smith reports, VIPER’s Project Scientist Anthony Colaprete pushed back against NASA’s assertion that VIPER would induce added costs after going through the standard series of environmental tests required to be cleared before it can launch to space. Colaprete noted that the VIPER rover has already passed launch vibrational and acoustic testing with no major problems, that is, with no substantial added costs to the mission. Thermal vacuum testing to simulate temperatures VIPER could face in space and on the Moon’s south pole is scheduled for end of August, wherein Colaprete doesn’t expect any surprises either because individual elements of VIPER have already passed this test prior to integration.

Did NASA prematurely award the VIPER CLPS task order?

Since NASA contracted VIPER’s delivery to Astrobotic in 2020, soon after the first batch of CLPS contracts in 2019 and—crucially—before any of them could fly, the aforementioned NASA OIG report on CLPS posits the following:

Inserting a larger lander to accommodate VIPER into CLPS’s early schedule interfered with a progressive development approach. This introduced the added risk of beginning the first large lander delivery before knowledge could be gained from the success (or failure) of smaller deliveries.

NASA has realized this in retrospect. As Jeff Foust reported on The Space Review:

Scaling up CLPS to accommodate VIPER, though, may have been premature. He [Joel Kearns, the NASA SMD deputy associate administrator for exploration] said VIPER required a “large and somewhat unique lander” compared to the smaller CLPS landers, but with the expectation at the time VIPER started that industry would move faster on those smaller landers, building up experience, than what happened.

“We originally thought in the government that the first landings on the Moon would take place in 2021 and 2022 by CLPS,” he said, but in fact just happened this year. “We and the companies have not yet accrued enough experience to probably understand how to smoothly deliver such a large and sophisticated payload as VIPER to the lunar surface.”

What next?

NASA has said it will consider expressions of interest from the US industry as well as international partners to fly VIPER at no cost to NASA before going ahead and disassembling the rover next year. It will be some time before the viability of alternative solutions proposed via this route becomes clear. In any case, the US Congress will decide if NASA will need to reconsider flying VIPER somehow or if the agency can go ahead with the formal cancellation it desires. You can help push for VIPER’s revival by signing a letter addressed to members of the US Congress explaining the mission’s importance— even if you’re a non-US citizen like myself. Either way, Astrobotic will still attempt to land Griffin on the Moon’s south pole for NASA under their existing $323 million CLPS contract, albeit with a drab simulated mass replacing VIPER.

Despite how NASA may put it, no other CLPS mission can perform the depth and breadth of science VIPER was supposed to. The advanced rover intended to explore areas in and around frigid permanently shadowed regions for over four months to help scientists determine the nature, accessibility, and abundance of the Moon’s water ice deposits. In comparison, most CLPS missions last a single lunar day (14 Earth days), are minimally mobile at best, and will carry only one of the four key VIPER instruments which otherwise were to work in tandem.

Results from VIPER were to feed into NASA’s planning of crewed Artemis missions but it would seem the first such astronauts will have to meet some of VIPER’s goals themselves—and even then they can’t meet them all. Never mind the separate fact that the crewed Artemis III mission is not realistically expected to launch until later in the decade. The only missions that actually hit the kind of broad as well as specific goals VIPER had are CNSA’s Chang’e 7 and the JAXA-ISRO LUPEX rover.

Many thanks to Open Lunar Foundation and The Orbital Index for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday. If you love this curated community resource too, join them and support independent writing and journalism.

ispace ready to rove

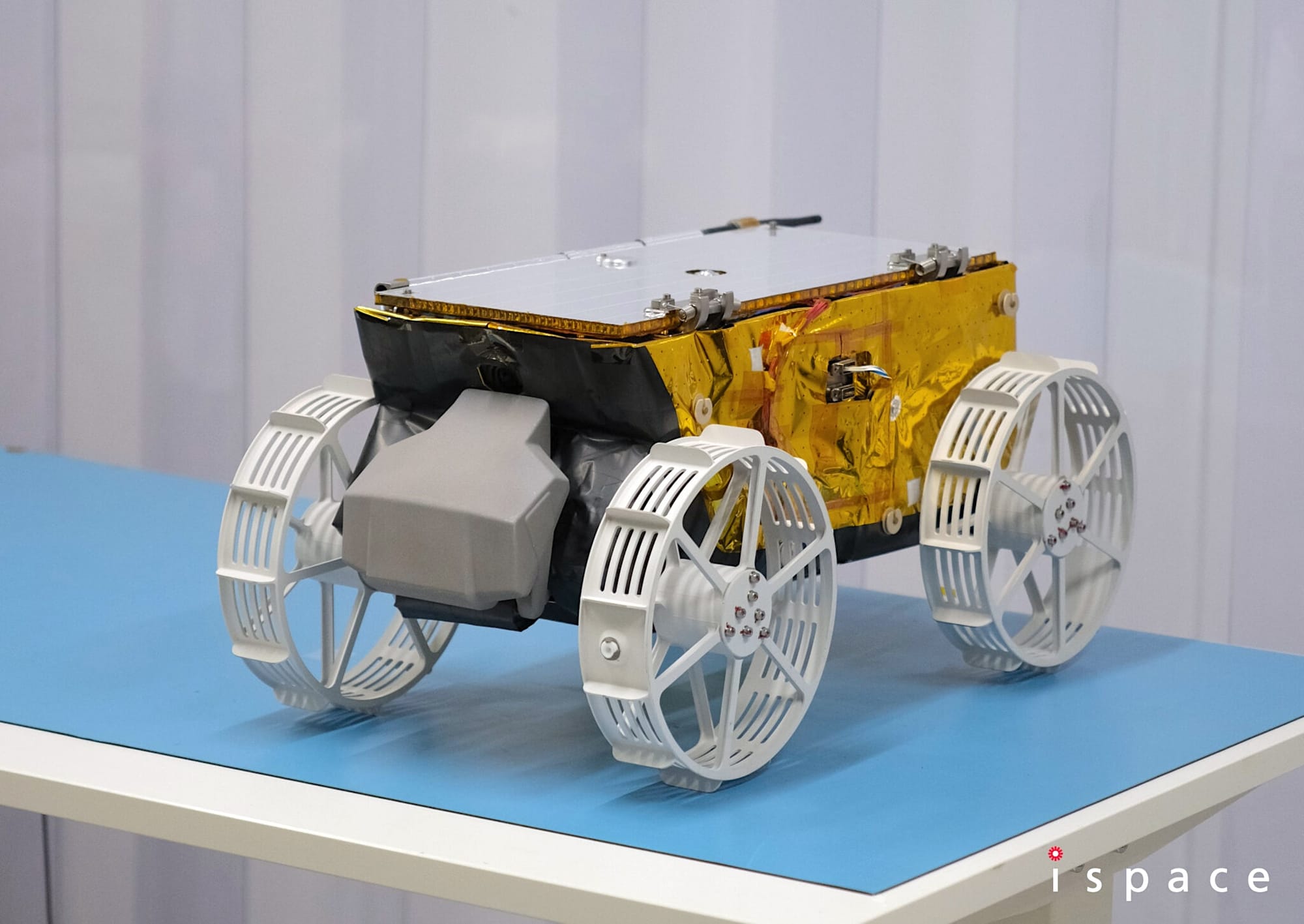

On July 25, ispace Europe announced completing building their flight rover, which will be aboard ispace Japan’s second Moon mission launching end of 2024 on a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket. This update follows the company completing environmental testing of the rover’s qualification model in April.

The 54-centimeter wide, 5-kilogram micro-rover made of carbon fiber-reinforced plastics will explore the Moon’s surface with an HD camera on its front and back. The rover will also have a back-mounted shovel from Epiroc AB using which it will collect lunar soil and transfer its ownership to NASA as part of the latter’s move to set precedence for future resource use under the US-led Artemis Accords. ispace Europe developed the micro rover with funding aid from the Luxembourg Space Agency under an ESA contract.

Next up, the rover will be integrated with the ispace lander in Japan. While the overall mission is named M2/RESILIENCE, reflecting the spirited reattempt following ispace Japan’s failed lunar touchdown attempt with the M1 mission in April 2023, the rover carries the theme with the name TENACIOUS. Relatedly, ispace Japan announced on June 27 that the mission’s lander passed thermal vacuum testing. ispace engineers have also verified commanding the lander and receiving data from it. The ongoing tests are part of a slew of launch and space environmental tests ispace is conducting at JAXA’s Tsukuba Space Center.

More mission updates

- On July 23, the second core stage of the SLS rocket arrived from Michoud to NASA’s Kennedy Space Center for final rocket assembly in the coming months, to be followed by its integration with the Orion spacecraft. If all goes well, this SLS rocket will launch the Artemis II mission by end of mid-decade, pushing four astronauts in the Orion capsule around the Moon and back.

- Ling Xin reports that China recently successfully test fired the high-energy hydrolox YF-75E engine. Three of these engines will power the third stage of China’s Long March 10 rocket, which will be the launch vehicle used to send astronauts to the Moon starting end of decade.

More Moon

- Following a £2.9 million award, the UK Space Agency is funding £4.8 million to a team led by Rolls-Royce to further develop a lightweight and modular autonomous nuclear micro-reactor with the hope of an initial demonstration on the Moon by 2030. This will help future missions survive frigid lunar nights at lower costs.

- The Luxembourg-based European Space Resources Innovation Center (ESRIC), in partnership with ESA’s Business in Space Growth Network, has launched an accelerator program to help co-fund European organizations focused on developing technologies related to prospecting, extracting, and utilizing lunar resources. To start off, the accelerator aims to provide a total of €1 million for the first batch of ideas.

- Ling Xin reports that on July 12, the non-profit Hungarian Solar Physics Foundation became the 14th non-country to join the China-led long-term scientific base on the Moon’s south pole called the International Lunar Research Station (ILRS).

- In honor of the women “human computers” and “Hidden Figures” contributing to early US spaceflight research as well as to the Apollo program, NASA has named one of the buildings in the Johnson Space Center as the “Dorothy Vaughan Center”.