Why explore Venus

Earth’s sister planet warns us that planetary climates can change dramatically.

Why study Venus?

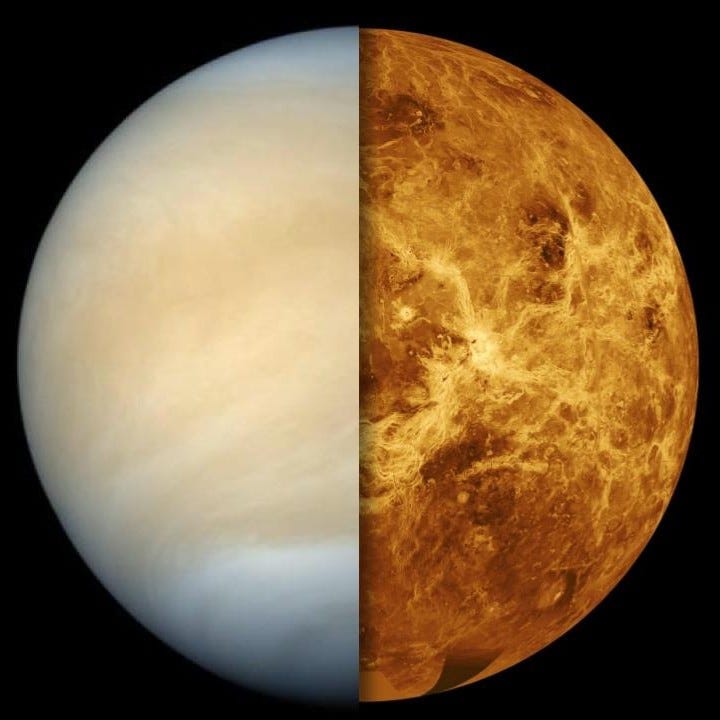

The Sun rises in the east and sets in the west, except if you are on Venus. That’s because it rotates on its axis in the opposite direction from other planets, and nobody knows why. This is just one of the many mysteries of Venus, a cloud-shrouded hellscape with an atmosphere 50 times denser than Earth’s, and average surface temperatures of 470 degrees Celsius—hot enough to melt lead.

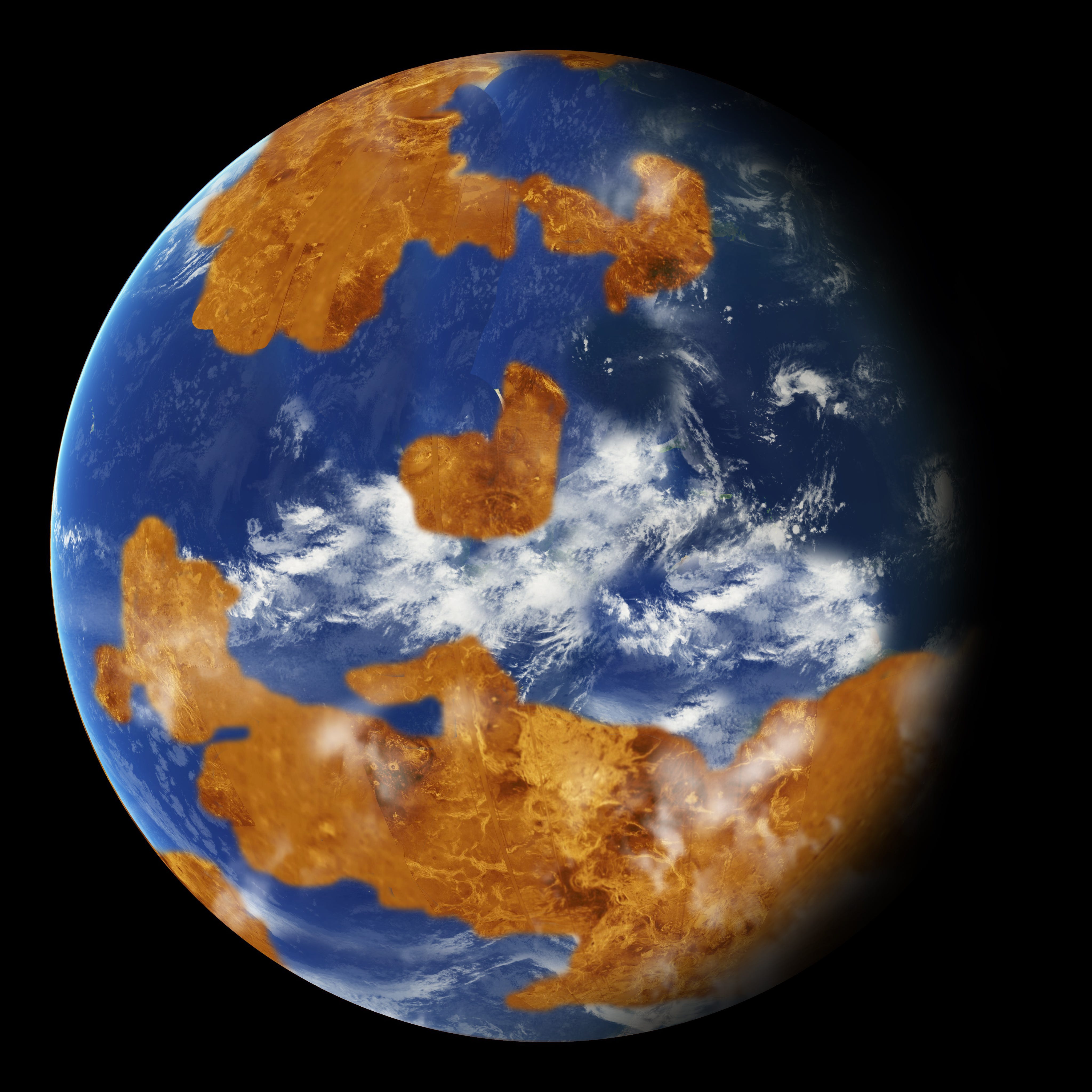

Venus is currently inhospitable, but it wasn’t always that way. Past missions there have observed granite-like rocks on the surface, which require abundant water to form. In the early solar system when the Sun was cooler, scientists think Venus may have had liquid water on the surface for two billion years—far longer than Mars, which may have had liquid water for 300 million years. Water is the key to life as we know it, so did Venus once have life?

Venus is the hottest planet in the solar system, even though Mercury is twice as close to the Sun and receives four times more solar energy. The reason? Mercury has no atmosphere, whereas Venus’ thick, carbon dioxide atmosphere creates a runaway greenhouse effect, trapping in heat. That’s also why unlike Mercury whose nightside can get as cold as -220 degrees Celsius, Venus continues to be equally hot even at night.

How did Venus transform from a potentially habitable world to its current hellish state? Studying Venus helps scientists get answers to questions like that while simultaneously gaining insights into what makes Earth a haven for life. Scientists also use Venus as a reference to understand how Earth-sized planets around other stars evolve and what conditions might exist there. To that end, Venus also helps scientists model Earth’s climate, and serves as a cautionary tale on how dramatically a planet’s climate can change.

There is also a slim chance microbial life currently exists in Venus’s upper atmosphere, where mysterious dark patches absorb more than half the solar energy the planet receives. This region, approximately 50 kilometers above the surface, has Earth-like temperatures and pressures. In September 2020, scientists announced that Earth-based radio telescopes have detected phosphine molecules in this region, which could be a biosignature of microbial life. Venus is on average almost three times closer to Earth than Mars, often shining as a bright evening star in our skies. Have we been looking for life on the wrong planet?

A brief history of Venus exploration

Venus was the first planet to be visited by a spacecraft. In 1962, NASA’s Mariner 2 flew by the planet and discovered it was a hot world with no self-generated magnetic field. The Soviet Union became the world leader in early Venus exploration after that.

The Soviet Union sent the Venera 4, 5 and 6 spacecraft to explore Venus’ atmosphere in the same decade. As the probes descended, their instruments revealed the dense atmosphere to contain 96% carbon dioxide and atmospheric pressures to exceed Earth’s by 50 to 100 times, depending on the altitude.

The Soviet Union then went on to successfully land ten spacecraft on Venus from 1970 to 1985 – the Venera landers labelled 7 through 14 and Vega 1 & 2. During their atmospheric descent, their instruments measured temperature and pressure profiles, elemental makeup of Venus’ clouds and their layering. After landing, these spacecraft lasted from a few tens of minutes to two hours at best under the harsh conditions. During that time, they took the first and the only images of Venus’ surface and also determined the chemical composition of nearby rocks. To this day, the Soviet Union remains the only nation to have landed spacecraft on the surface and transmitted both data and images back to Earth.

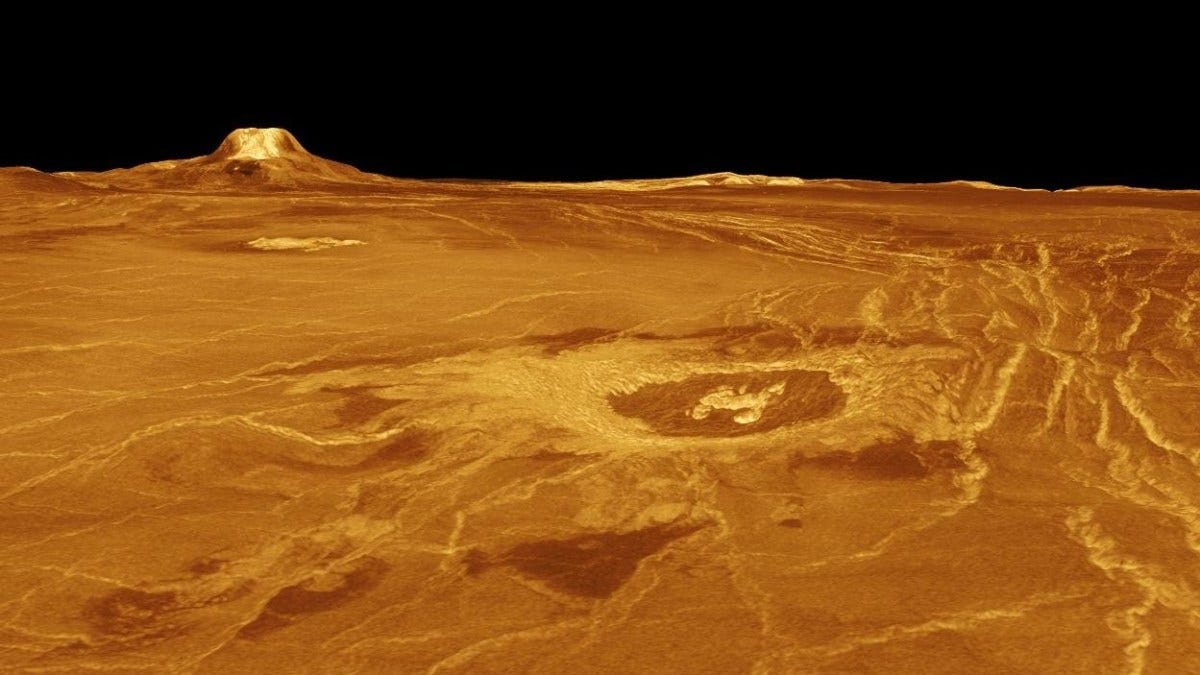

Due to thick clouds, it’s very difficult to see Venus’ surface without radar. NASA’s Magellan orbiter, launched in 1990, used radar to map Venus’ surface at the highest resolution to date. Magellan revealed that all of the planet’s impact craters are formed within the last 700 million years. This implies that Venus’ surface was completely reshaped by a worldwide volcanic event in its recent geologic past—but exactly what happened is still up for debate.

Magellan also found no sign of plate tectonics. On Earth, plate tectonics is a process in which sections of the planet’s outer crust glide over the mantle—the rocky inner layer above the core—allowing heat to escape through volcanism. Since we think Venus’s interior is similar to Earth’s, the lack of plate tectonics means that volcanoes on Venus must work differently than on Earth.

The European Space Agency launched the Venus Express orbiter in 2006. By observing hotspots on the surface and changing sulfur dioxide levels in the atmosphere over six years, the spacecraft collected the best evidence yet of active volcanism on Venus. Venus Express also discovered granite-like rocks across the planet that require abundant liquid water to form, solidifying the idea of the planet having past oceans.

Japan’s Akatsuki spacecraft is the only probe currently orbiting Venus. It discovered a giant stationary wave in Venus’ atmosphere that stretches across the planet, the largest of its kind in the solar system. Akatsuki continues to study Venus’s atmosphere in frequencies of light that human eyes cannot see, specifically ultraviolet, infrared, microwave and radio, so as to paint a complete picture of happenings on Venus.

Upcoming Venus missions

Only three missions have visited Venus in the past 30 years, and many scientists feel new missions are long overdue. The idea that Venus used to be at least as habitable as Mars and for a much longer period warrants further exploration and can have profound implications. Thanks to technological advancements in the last two decades, we can now unravel many of Venus’ mysteries.

India aims to launch a Venus orbiter called Shukrayaan in December 2024 equipped with a radar and infrared camera to map the surface. It will have a payload capacity of about 100 kilograms and study Venus for four years from a polar orbit of 200 x 600 kilometers. The spacecraft will carry both Indian and international science instruments. One, called VIRAL (Venus Infrared Atmospheric Gases Linker), will be co-developed by the French and Russian space agencies.

NASA's DAVINCI mission will launch between 2028 and 2030. It consists of an orbiter and an atmospheric descent probe. The probe will make high precision measurements of trace gases in Venus’ atmosphere, helping firmly determine how much water Venus’ oceans had and how long they existed.

NASA's VERITAS orbiter will launch between 2028 and 2030. It will have a radar instrument with up to 100 times higher resolution than Magellan. This will give scientists a better handle on Venus’ geology and evolution and also reveal why the planet lacks large-scale plate tectonics.

The European Space Agency's EnVision mission will launch no earlier than 2031. The orbiter will provide a comprehensive view of Venus, from the core all the way to its upper atmosphere.

Scientists hope that results from all these future orbiters will pave the way for renewed surface exploration of Venus, including roving platforms built specifically to endure the harsh environment.

Originally published at The Planetary Society.

Like what you read? Support me to keep me going.