The tiniest of impact craters [Guest post]

Small meteorites constantly bombard the Moon and create micro-sized craters.

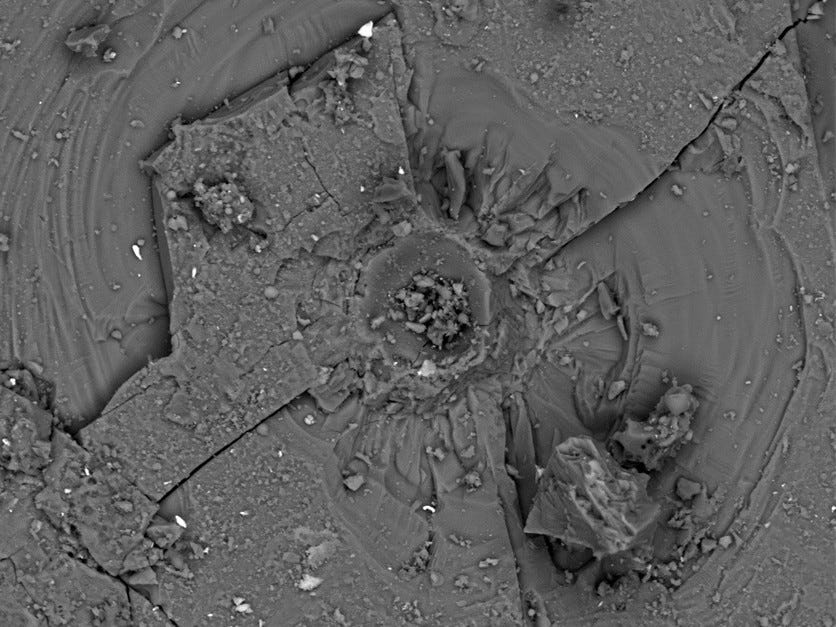

When we think about craters on the Moon, we usually think of ones that can be seen with a telescope or in images sent by spacecraft around the Moon. But there are also ones we can only see with a microscope. Here’s a micro-sized crater on a Moon rock!

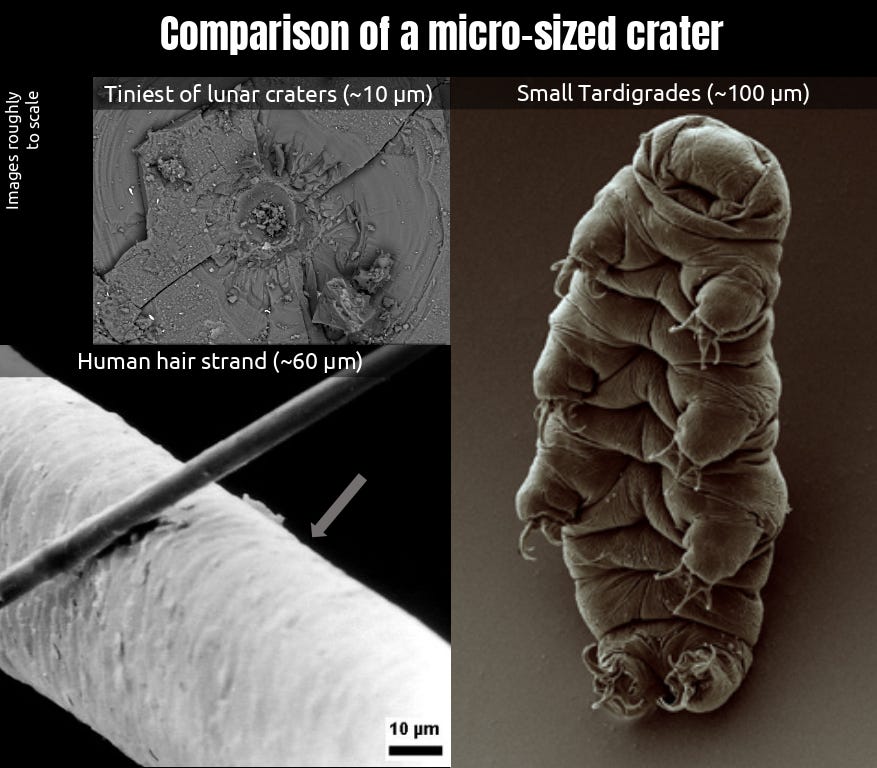

Astronauts on the Apollo 12 mission brought 45 rocks from the Moon to Earth. The featured micro crater in an olivine mineral grain is from the rock 12075, as seen in a scanning electron microscope. It spans a little more than 10 microns, compared to the ~60 micron width of a human hair strand. The grain of dust that created this tiny impact crater was probably only about a micron wide. Here's a quick size comparison of a micro crater with a tardigrade and a human hair strand. Thanks Dad for the suggestion!

We don’t see such micro craters on Earth, as small meteorites burn up in our atmosphere before they even reach the ground. We see some of those burning things as “shooting stars”, but the grain that made this impact is too small even for that. Because the Moon doesn’t have an atmosphere, every little piece of cosmic dust can make an impact. Such small impact craters are called “micrometeorite impacts” or sometimes “zap pits”.

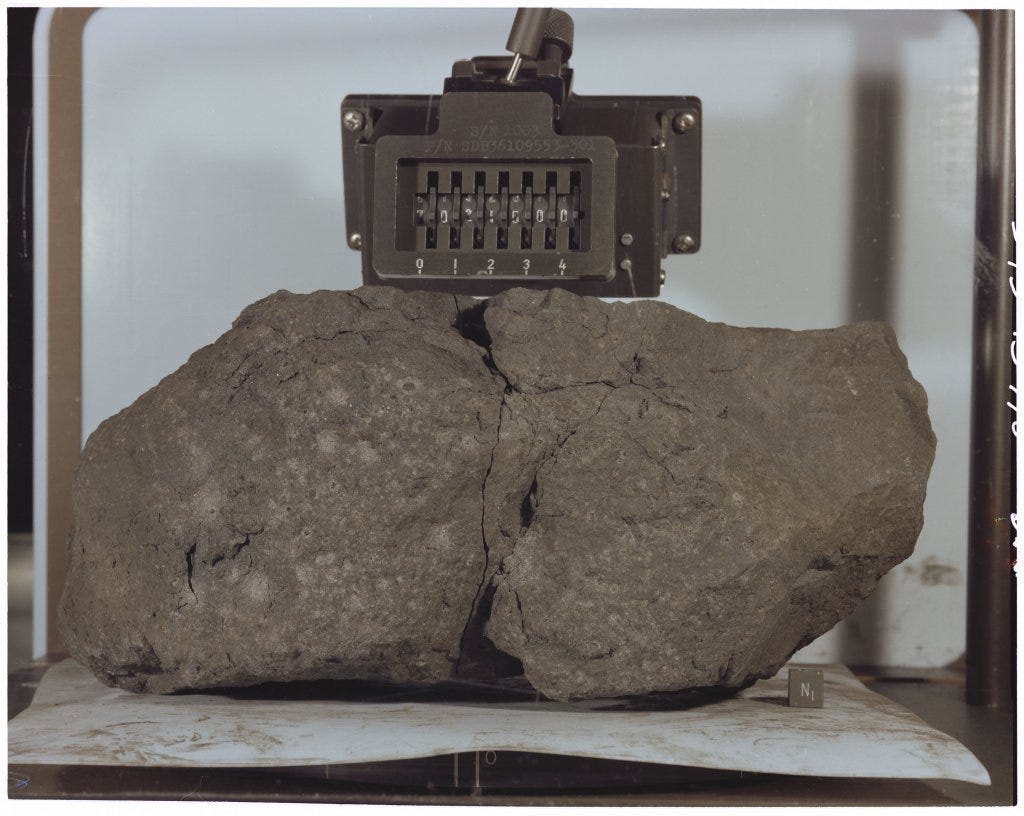

Some of the rocks that the Apollo program returned were covered with micro craters on the surface, but just on one side, the side that faced upwards on the Moon and was exposed to space. Like this one from Apollo 17, lunar rock 70215.

Micrometeorite impacts are part of the process of “space weathering”, which slowly changes the properties of lunar rocks and soils, making them appear darker with time. That is why young craters are so bright.

Impacts expose fresh material that is bright, but because of all of these tiny impacts and effects of the solar wind, those rays disappear over millions of years and the soil gets dark.

Micrometeorites could be a hazard to future lunar visitors and residents. While these tiny grains seem to hit all the time on a geologic time scale, on a human scale, they are actually pretty rare. You’d have to be very unlucky to get hit by one on a short EVA, but if you are designing habitats for long-term use, they are definitely something you need to take into account.

Did you know? You can view Apollo samples with a virtual microscope! Here’s rock 12075

This is a guest post by Dr. Sarah Noble.

Sarah Noble is a planetary geologist and a Program Scientist in the Planetary Sciences division at NASA HQ. Her area of expertise is space weathering processes. She was the Program Scientist for NASA's LADEE spacecraft, and is currently the Program Scientist for the Psyche mission.

→ Browse the Blog | About | Donate ♡