How we got to know the Moon’s gravity is lumpy

The Moon's gravity anomalies have been crashing spacecraft since the 1960s.

The fact that the Moon’s gravitational field is lumpy was first noticed by the Soviets when they found that their Luna 10 spacecraft was significantly deviating from its orbit. Shortly after, NASA also noticed their “Lunar Orbiters” to deviate from their paths in low lunar orbit by up to 100 times more than expected. So NASA took these gravity ‘anomalies’ into account for successfully steering and landing humans on the Moon with the Apollo missions.

Both Apollo 15 and 16 put a small satellite in low lunar orbit. Despite mission planners having accounted for Moon’s lumpiness, both the satellites crashed into the lunar surface. The Apollo spacecraft, which took different routes than the satellites, were unaffected. Nevertheless, it was clear that the Moon had more gravity surprises in store.

In 1998, NASA launched the Lunar Prospector mission, which mapped the Moon’s gravity anomalies in great detail. Typically, you’d expect a region with a mountain to have higher gravity than a region with a crater, and that’s what it observed across the Moon for most small-to-medium-sized mountains and craters. But Lunar Prospector’s data also revealed that some large features, such as a few dark lava plains, have higher gravitational pull than even bright, rocky regions!

Scientists thought that this could be due to dense lava deposits in these large craters, which can be filled as deep as six kilometers. But that could only account for some of the concentrated mass in such regions. Where is the rest of the mass?

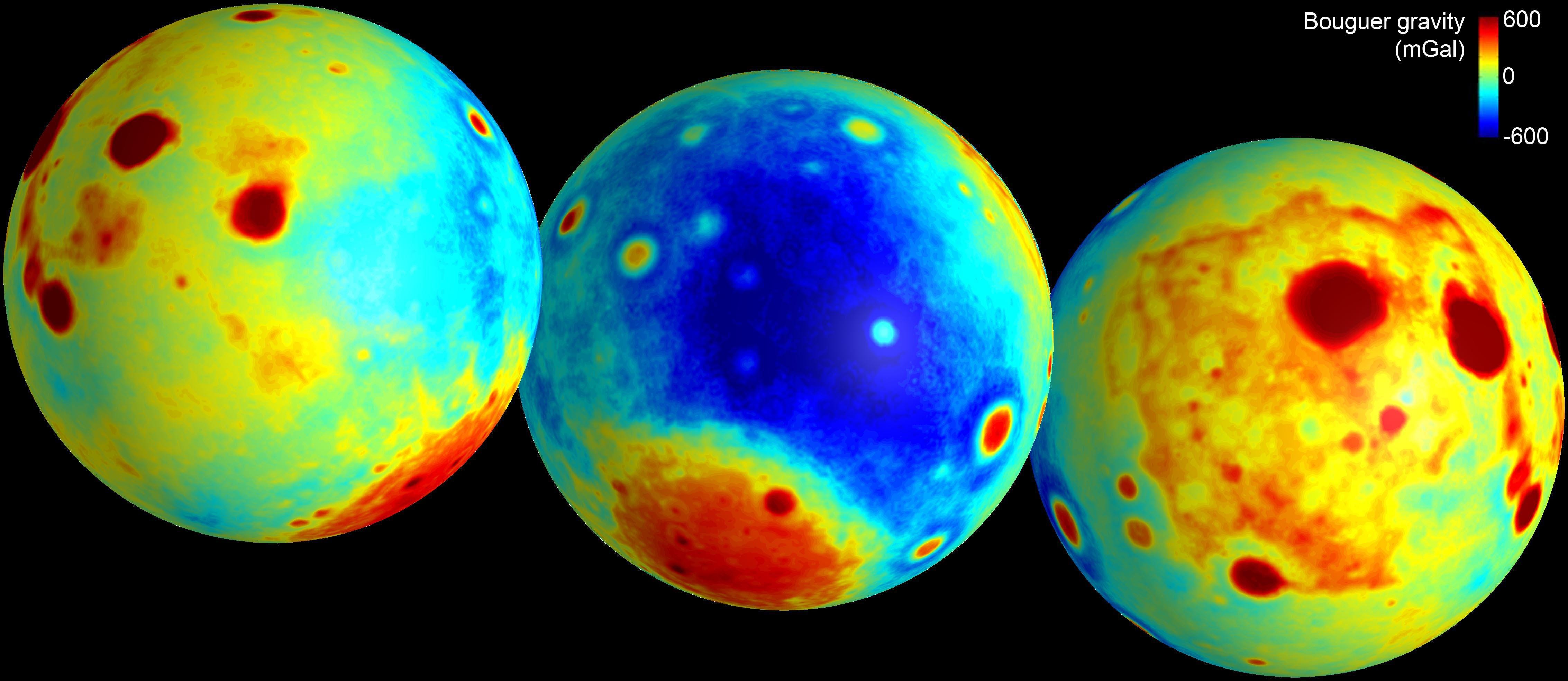

Using the highest resolution mapping data from the purpose-built twin GRAIL spacecraft NASA launched in 2011, scientists think they figured out the missing mass mystery.

Most of the Moon’s vast, dark lava plains are sitting on top of huge, deep, ancient craters. These craters formed 4.1 to 3.8 billion years ago when large asteroids and comets were bombarding planets and moons in the solar system. Over the next several hundred million years, the Moon’s vicious volcanoes filled these craters with lava, which is why they don’t look like craters anymore. But these ancient craters are where most of the Moon’s gravitational highs hide.

The large asteroid and cometary impacts forming these craters had cut into the Moon’s crust so deep that they excavated the denser mantle material sitting below. This in turn must have pulled in more nearby mantle material, making the region a mass concentration i.e a mascon.

Mascons have also been found on other bodies like Mercury and Mars. Given that they have been extensively cratered much like the Moon, it makes sense. There’s even a mascon on Earth near Hawaii.

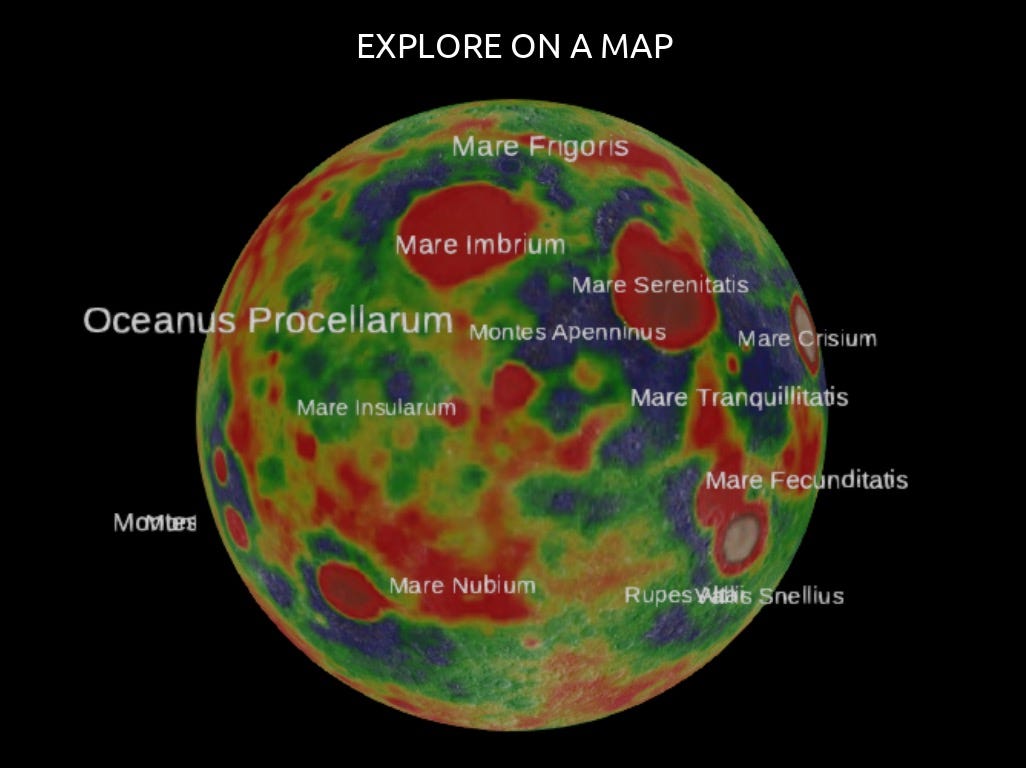

NASA has made an interactive Moon map with the GRAIL gravity data overlaid on it, click on the image below to explore it yourself and have some fun. Emily Lakdawalla has a detailed article explaining the Moon’s gravity anomalies.

This post is coming to you from a COVID isolation center. I have a mild case of COVID-19. I’m physically fine though, and should be back home soon so there’s nothing to worry about. Nevertheless, I want to thank the brave service workers here because of whom I have all my basic needs sorted, and could keep my work going and get this article out. :)