Moon Monday #92: Artemis I launch delay, skeleton Starship, powering a lunar base, and more updates

The Sun isn’t rising for the SLS just yet

The super heavy-lift SLS rocket just can’t catch a break. NASA scrubbed today’s launch of SLS for the Artemis I mission to send an uncrewed Orion spacecraft around the Moon and back. The launch was called off because of a persistent issue that is preventing proper “bleed” conditioning of the third RS-25 engine on the rocket’s core stage. Essentially, engineers aren’t able to flow liquid hydrogen through the engine to make it cool enough for launch.

NASA said on the livestream that the rocket will not be drained of its more than 2 million litres of propellant just yet, as engineering teams try to figure out the root cause of the issue. This “bleeding” technique is something that teams couldn’t test during earlier wet dress rehearsals because of a then recurring hydrogen leak, which was later fixed. Assuming the issue is solved, the next launch attempt for Artemis I is a two-hour window starting at 12:48 PM EDT on September 2. NASA’s official Artemis Blog should have more details on the issue and next launch attempt soon.

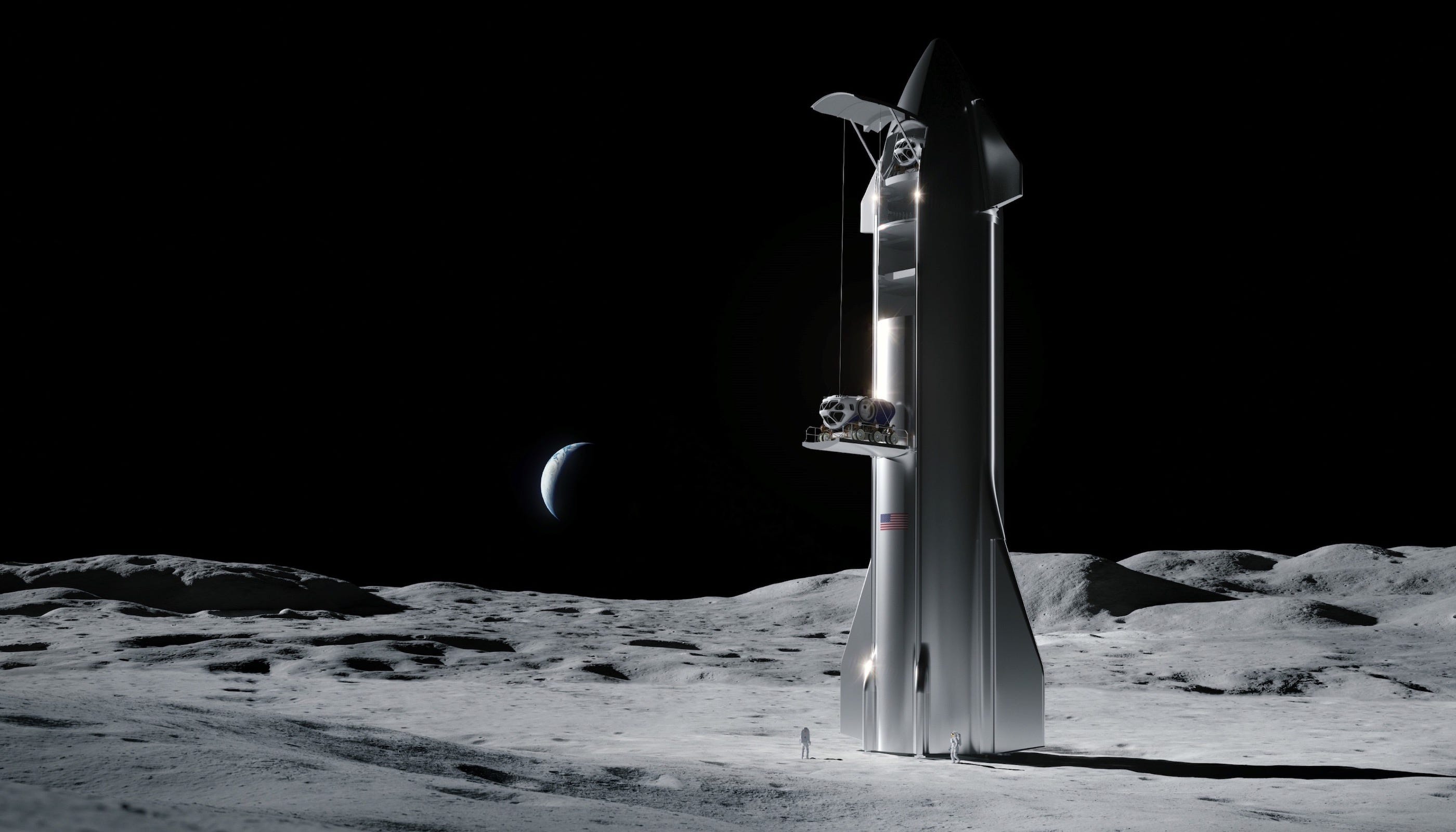

A skeleton Lunar Starship and Artemis Base Camp

At the LEAG 2022 Annual Meeting last week, the head of the Human Landing System (HLS) program Lisa Watson-Morgan said that the robotic test flight of SpaceX’s Lunar Starship in 2024—the flight preceding the highly anticipated Artemis III crewed landing—isn’t required to takeoff post-landing. She clarified that the test Lunar Starship will be a “skeleton” version of the actual crewed lander, and that the baseline requirement is only to prove a safe touchdown. It wouldn’t be surprising if SpaceX decided to demonstrate a launch from the Moon anyway.

Lisa Watson-Morgan added that the test lander will carry at least one payload in addition to a host of imagers and sensors. When asked about its landing site, she specified that it likely won’t touchdown in any of the recently announced Artemis III candidate landing regions to avoid contaminating their scientific potential. Relatedly, she also assured people that given the criticality of Lunar Starship’s elevator, it’s being designed to be multi-fault tolerant.

Logan Kennedy, Artemis surface lead, revealed more on how NASA plans to complement the agency-requested sustainable landers from SpaceX and a competitor, which will ferry Artemis astronauts to and fro the Moon’s surface after Artemis III.

In order to sustain and extend human presence post-2030 under Artemis Base Camp, whose stay duration NASA revealed at the meeting to be of 30 days initially, the agency will ask companies to develop “Human-Class Cargo Delivery Landers (HDL)”. These should be capable of delivering 12,000 to 15,000 kilograms of cargo to the surface, including crew-critical supplies, scientific payloads, large rovers, habitat modules, and more. NASA also noted that all crewed missions will target summer stays at the Moon’s south pole because it has relatively much better lighting conditions than local winter.

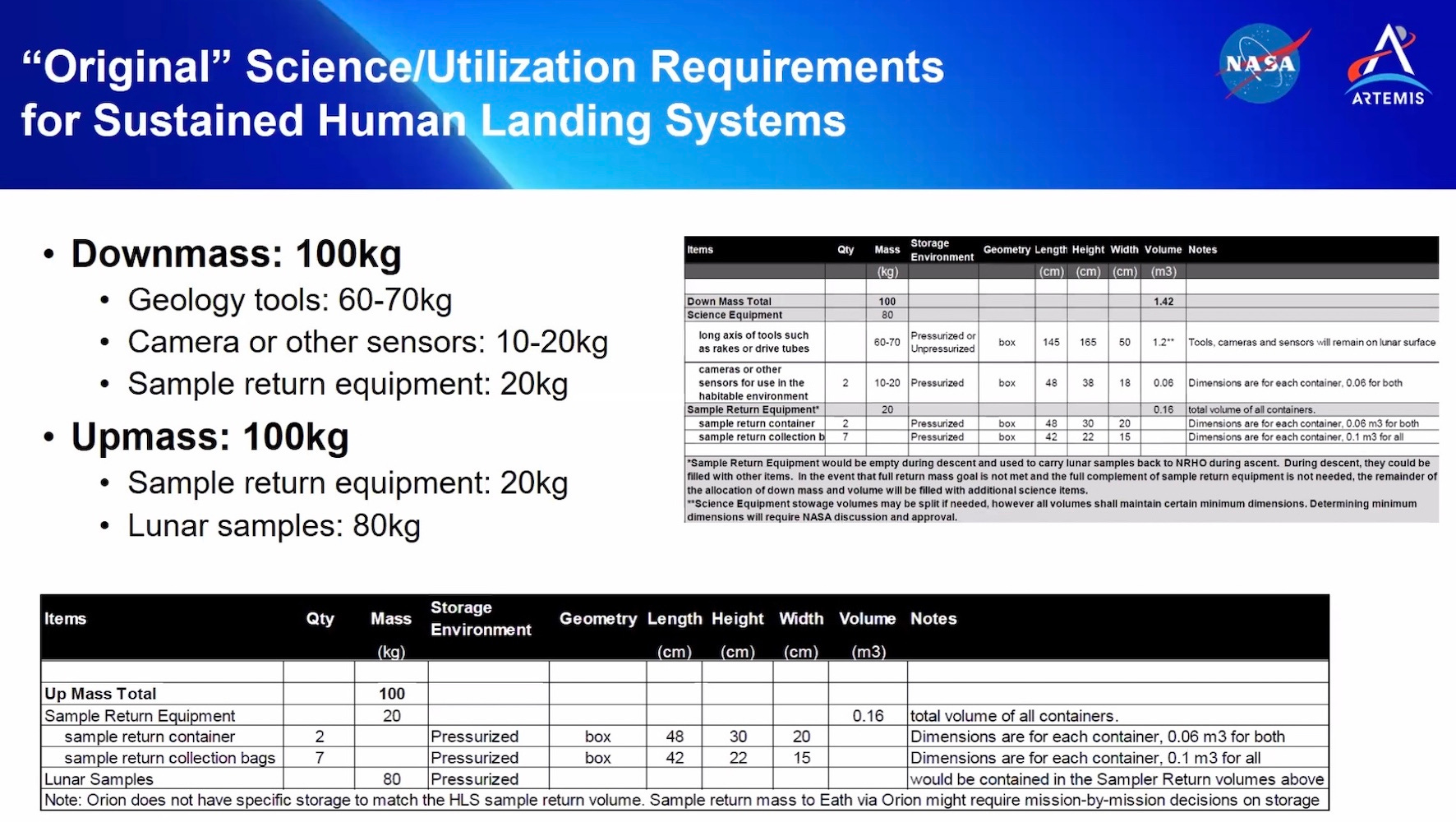

Kennedy also said that while the first HLS Starship with astronauts will carry only 100 kilograms of cargo to the surface and back (including samples), later missions will increase that to 182 kg to the surface and 160 kilograms back, with a goal of 1,000 kilograms both ways. However, a small note at the bottom of one of his slides read:

Orion does not have specific storage to match the HLS sample return volume. Sample return mass to Earth via Orion might require mission-by-mission decisions on storage. NASA is looking into handling excess mass in different ways.

Many thanks to Epsilon3 for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday.

Thanks also to Pradeep and Abhinav Yadav for supporting my independent writing.

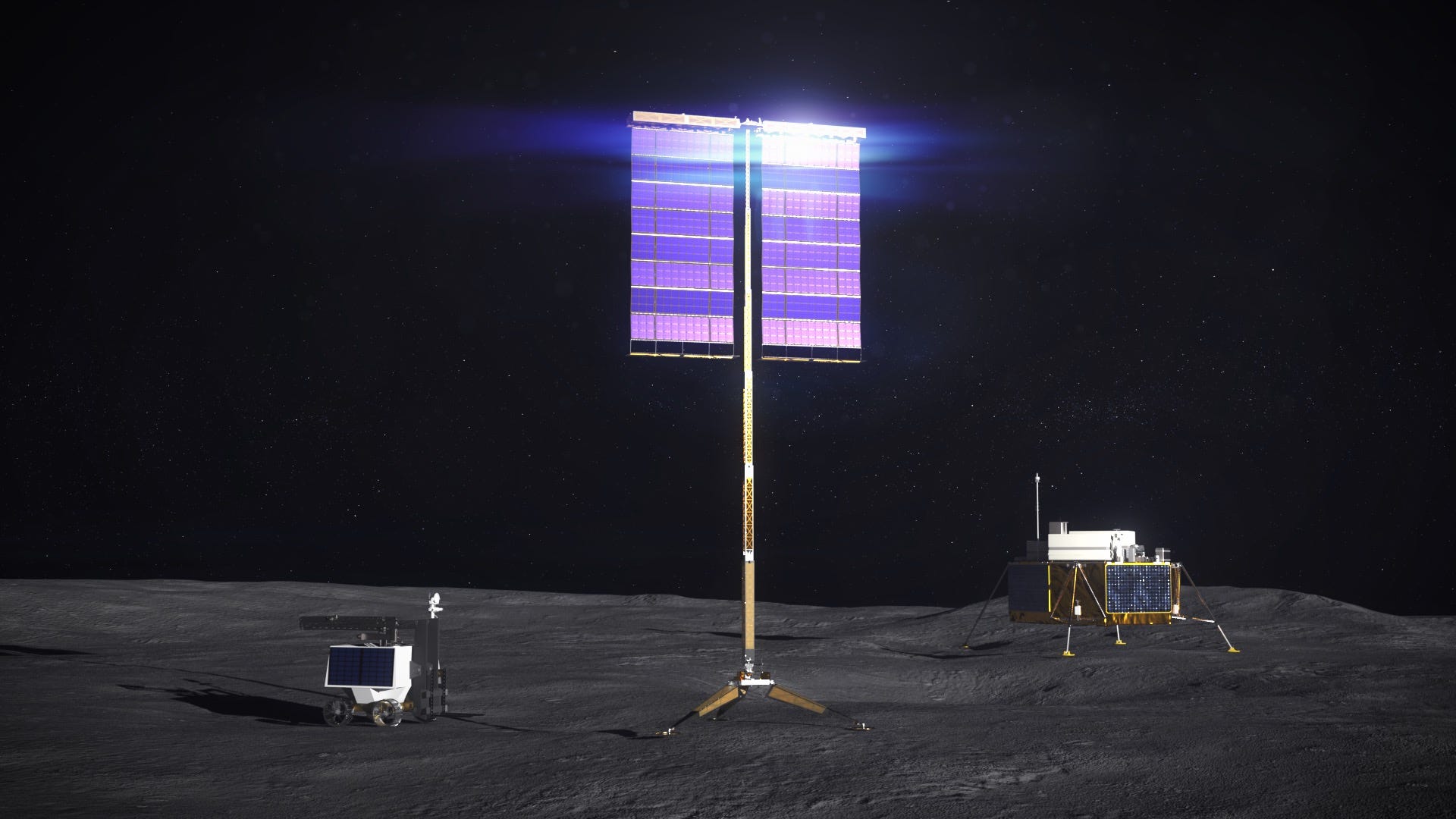

Powering the Artemis Base Camp

The Sun always being close to the horizon on the Moon’s rocky poles means something as mundane as a small rock or a gentle slope in the wrong direction can deprive solar panels on future habitats or other hardware of sunlight. Extensive studies from ESA and NASA have shown that even the best high-altitude sites would need solar panels placed at least 2 meters above the surface to generate adequate power, and more than 5 meters for substantial power.

Following an initial developmental award in 2021 part of the agency’s VSAT project, NASA awarded a total of $19.4 million to Astrobotic, Honeybee Robotics and Lockheed Martin last week to build and test prototypes of vertical solar arrays. These systems must auto-deploy up to 10 meters in height, retract for relocation, be stable on steep terrain, be resistant to abrasive lunar dust, all while minimizing mass and stowed volume for easing delivery to the Moon. NASA will downselect one system for a possible test flight near end of decade and ultimately use it for Artemis Base Camp.

China’s march to the Moon

With the fourth phase of China’s lunar exploration project being approved in December 2021, the country is amid a long leap in exploring our cosmic neighbor. But China has its sights much further, with officials recently claiming progress towards crewed lunar landing, Andrew Jones reports. While China hasn’t yet officially approved a formal human Moon landing project, it has long begun building many of the necessary elements to pull off the feat.

China is building a new (and possibly reusable) super heavy-lift rocket, derived from its existing venerable Long March 5, with a set purpose to send humans to the Moon before 2030. Capable of launching up to 70,000 kilograms to low Earth orbit and up to 27,000 kilograms on a trajectory to the Moon, it matches the capacity of the current SLS rocket, and is nearly thrice that of the Long March 5 and SpaceX’s Falcon 9. China is targeting an Earth orbit test flight with its new generation crewed spacecraft using a smaller two-stage version of the rocket in 2026.

Hardware development for the previously known super heavy-lift Long March 9 rocket has also been progressing well. When ready around 2030, it will be able to launch 140,000 kilograms to low Earth orbit, and 50,000 kilograms on a trajectory to the Moon. At least initially, China intends to use Long March 9 to deliver huge amounts of cargo to the joint Sino-Russian International Lunar Research Station (ILRS), a long-term robotic and crewed scientific base on the Moon’s south pole. Last we heard, China and Russia formulated a Declaration for ILRS in September 2021 to clarify the project’s general principles and how international entities can participate.

More Moon

- CAPSTONE crossed its farthest point from Earth. Next up? Arch its way back to the Moon for orbital capture on November 13.

- SpaceNews reports that the Lunar Trailblazer orbiter, intended to launch in 2023, will undergo a NASA continuation/termination review due to cost overruns by spacecraft contractor Lockheed Martin. I recently wrote how Trailblazer will give us unprecedented high-resolution global maps of the amount, distribution, and state of water across the Moon. Even when assuming a 200% cost increase from the $55 million SIMPLEx mission cap, Trailblazer would provide scientific data for its targeted themes on par with NASA’s Discovery-class missions for about five times cheaper. I hope this mission critical to the lunar water story makes it to the launchpad as teams work on controlling its cost.

→ Browse the Blog | About | Donate ♡