Moon Monday #217: Red A-CLPS 🔥💍

Also drills, flying regolith, a hard landing, Moonlight, and many more mission updates to quench the lunatic in you.

US-based Firefly Aerospace’s Blue Ghost Moon lander part of NASA’s CLPS program continued its nominal streak of payload operations until just after the end of lunar day on March 16, achieving virtually all of the mission goals it set out on.

On March 14, Blue Ghost captured a total solar eclipse from the Moon, a mesmerizing world’s second recording of this celestial clockwork that humans have otherwise only observed from Earth as lunar eclipses. Many people are assuming the eclipse ring to be from the Earth’s surface edges but that’s wrong. Earth is much bigger than our Moon, and so the ring glow is from sunlight refracting through our Earth’s outer atmosphere. What’s remarkable is that Blue Ghost made these observations across five hours on battery power amid surrounding surface temperatures dropping far below 0°C and peaking to a frigid -170°C. In a way, this was a mini demonstration of Blue Ghost trying to work into a lunar night, something the spacecraft repeated at the end of the local day on March 16 for about 5 hours as planned.

Related: How Chandrayaan 1 captured a terrestrial solar eclipse from Luna

Since March 3, Blue Ghost was also intermittently operating the LISTER drill, which is jointly developed by Honeybee Robotics & Texas Tech University and flight-funded by NASA. While LISTER’s intended drilling depth was up to three meters underground, according to Firefly’s latest release the drill went up to about a meter into the surface. Data from LISTER will help scientists characterize heat flow in the Moon’s interior as well as other thermal properties, and from it ascertain our knowledge of how our Moon evolved. ISRO’s Chandrayaan 3 Moon lander performed a similar but complementary experiment in 2023 using a thermal probe, and whose first set of results have been published in Nature earlier this month.

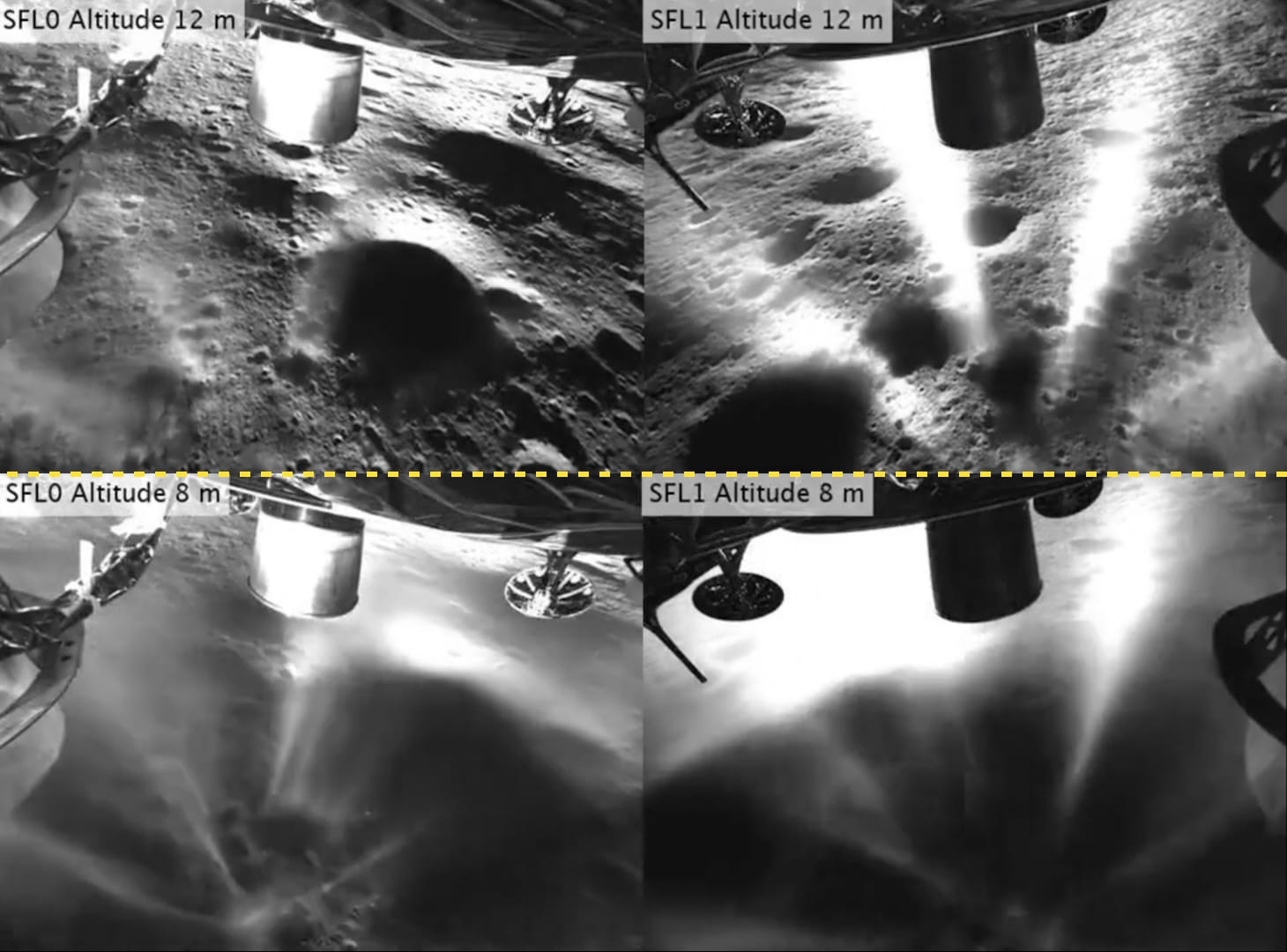

NASA has released initial pictures taken by the agency’s multi-camera SCALPSS payload onboard Blue Ghost during the lander’s last 28 meters of its lunar descent. Blue Ghost’s thruster plumes vigorously kicked up lunar dust, soil, and rocks—collectively called regolith. The full suite of up-close SCALPPS images will help lunar scientists and engineers better understand how rocket plumes blast out lunar soil and affect the local lunar environment, and thus how best to protect future astronauts, critical hardware, and long-term habitats on the Moon. NASA aims to make the payload’s data public within six months.

The first version of SCALPSS flew on Intuitive Machines’ first CLPS lander last year but couldn’t work because the spacecraft had an anomalously hard landing. NASA is sending the third version of SCALPPS on Blue Origin’s Blue Moon Mark I lander targeted for launch later this year. NASA says the new SCALPPS will be delivered to Blue Origin by end of March. The agency is interested in this flight because unlike smaller landers like Blue Ghost, the massive Mark I will generate high enough trust to allow NASA to gauge plume effects at the scale of large crewed (Artemis) landers.

Firefly says the rest of the NASA payloads onboard performed well too . The retroreflector atop Blue Ghost successfully reflected laser pulses from Earth-based ranging observatories. LEXI captured X-ray images to study how the solar wind interacts with Earth’s magnetic field. The RAC instrument noted how lunar regolith sticks differently to different materials on the Moon, which will better inform scientists and engineers on how to better protect future human and robotic explorers from notoriously sticky and jagged lunar dust.

Many thanks to The Orbital Index, Kris Zacny and Ben Hockman for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday! If you too appreciate my efforts to bring you this curated community resource for free and without ads, support my independent writing. 🌙

Still a hard landing for IM-2?

On March 6, Intuitive Machines’ second CLPS lander called Athena landed on the Moon’s south pole around 85°S but ended up resting on its side and inside a cold crater such that it couldn’t generate enough solar power for a single Earth day and died without accomplishing the vast majority of its IM-2 mission objectives. It turns out Athena’s landing might not have been much better than last year’s hard-landed IM-1 either based on multiple reports.

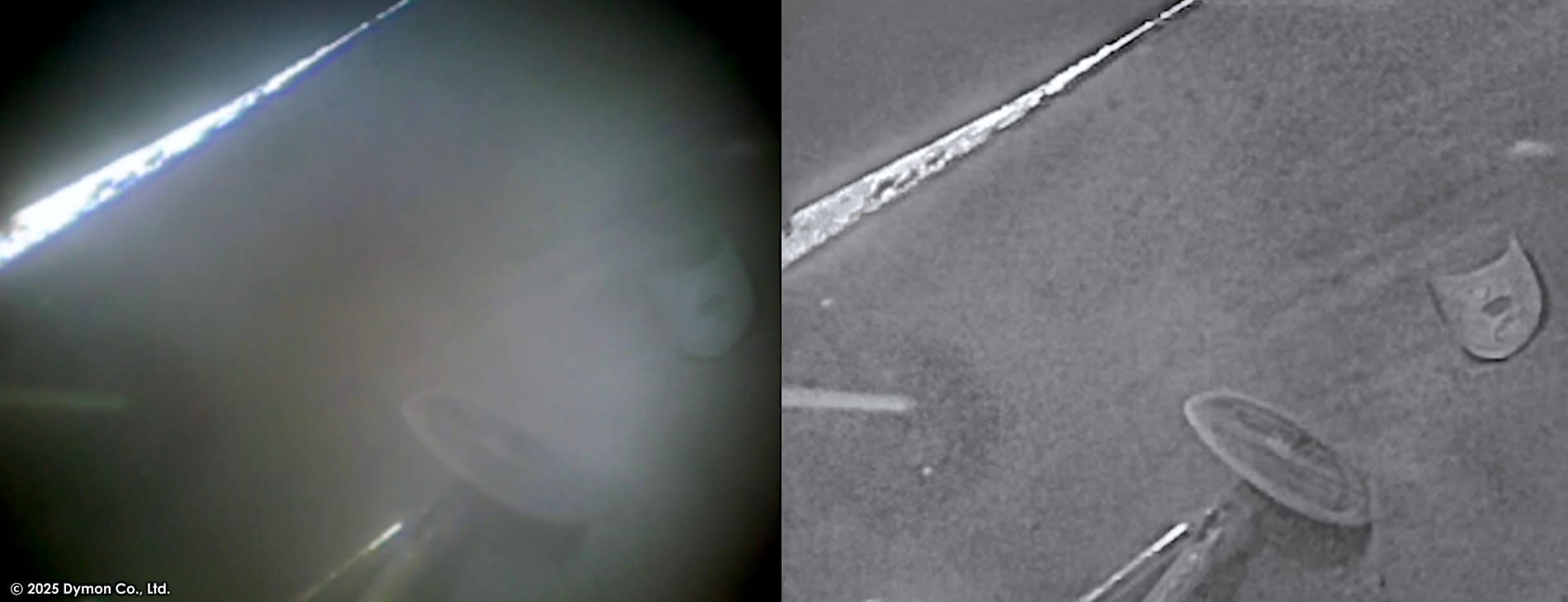

A blog post by the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera team mentions that Athena “hit the surface faster than intended”. While Japanese company Dymon’s tiny YAOKI rover onboard Athena couldn’t be deployed due to the lander being sideways, it took images from its hosted position which suggest that a lander leg might have broken off this time too. While that inference is speculative, YAOKI showcases how independent payloads enable more transparency on a mission by offering all they know. Analysis by Scott Manley using YAOKI images and other pieces of data also suggests that Athena may have come in laterally faster than expected just before hitting the Moon and toppling over. Well, for a nominal landing scenario, a lander could in principle leave a fine trail while laterally diverting to a safe landing spot using its hazard avoidance system but with Athena’s altimeters not working, the lander wouldn’t have known with good certainty how far off ground it is.

Eric Berger reports that Athena toppled over upon hitting the surface, and skid and rotated along the ground, gathering some regolith over itself and its solar panels before coming to a stop in a shadowed crater as cold as -173° Celsius. Now, many people are attributing the coldness as the reason for the mission failure. While that’s not false, it’s also not primarily relevant because broad ranges of pre-cryogenic and sub-cryogenic temperatures at the Moon’s poles are a well known fact. The environment is accounted for in mission planning and its contingencies.

Sadly, all of the issues discussed above is something the intentionally fuzzy language used by Intuitive as a publicly traded company will never tell you clearly and upfront through their direct communications, even though the mission hosted more than $100 million worth of US taxpayer money through NASA. The lander technically made it to the Moon and conducted very limited operations, and that’s something to acknowledge—but the mission itself failed, something to also acknowledge and certainly not forget when writing or talking about it in the future.

More mission updates

- Without providing any role-specific explanation, NASA has closed its offices of the ‘Chief Scientist’ and ‘Technology, Policy, and Strategy’, citing only broader workforce reduction orders under the new US administration. Both offices led and enabled cross-cutting work across NASA centers crucial to the agency’s and country’s scientific, technological, and geopolitical space goals, including those under Artemis. Marcia Smith has best covered the move’s impact.

- On March 9, ULA delivered to NASA the upper stage of the SLS rocket for the crewed Artemis II Moon mission targeting launch next year. Technicians will next fuel the upper stage and later stack it atop the rocket’s core stage via an adapter. On February 19, NASA completed stacking the twin solid rocket boosters that will be attached to the rocket’s core stage.

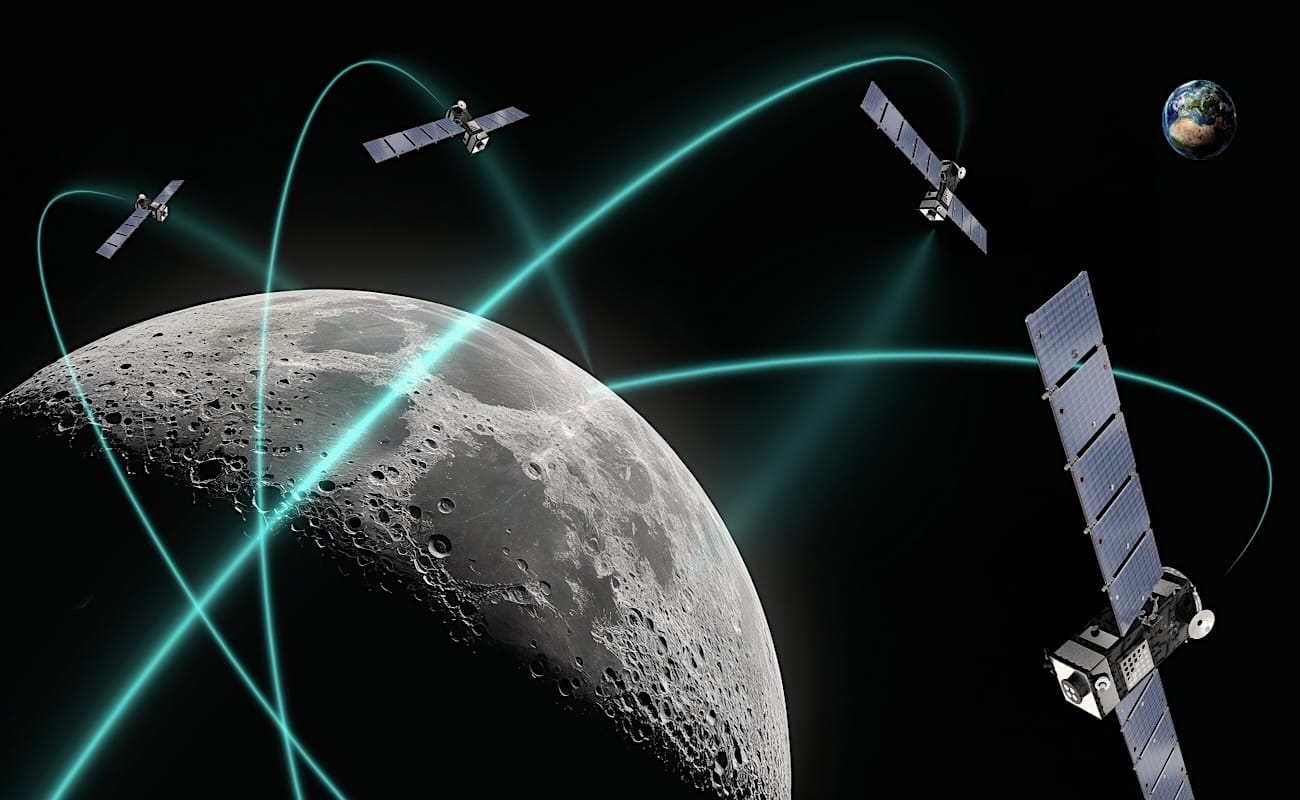

- The four lunar navigation satellites part of ESA’s upcoming Moonlight navcom constellation will be built by Thales Alenia Space as part of the Telespazio-led consortium, which won ESA’s competed selection last year for ~$134 million. Moonlight will majorly serve hardware on the lunar south pole region. The launch of UK’s SSTL-built, 280-kilogram Lunar Pathfinder communications orbiter in 2026 onboard Firefly’s second CLPS lander will constitute ESA’s first Moonlight element. ESA signed a $23.5 million contract with SSTL in September 2021 to get communications services from Lunar Pathfinder. As such, ESA will be Moonlight’s anchor customer but expects the consortium to seek lunar navcom customers globally. ESA is targeting end of decade for the full Moonlight constellation to be operational.

More Moon

- ESA is requesting research proposals by April 21 to assess the economic viability of local resource utilization on the Moon. ESA will co-fund the research in partnership with academia or industry. The research output must include a reference financial model ESA can use for its own strategic lunar exploration planning.

- I wrote this piece for the Open Lunar Foundation (a Moon Monday sponsor): As Moon missions mount globally, we need to preserve future exploration and science

- If you’re in Bangalore this Sunday, March 23, come over for the inclusive open discussion on all things space organized by WoAA India (Women Of Aeronautics & Astronautics India).