Moon Monday #113: A volcanic dome for NASA CLPS, a crusty site for Chandrayaan 3, Pangaea for astronauts, and more

NASA really wants to visit our Moon’s volcanic Gruithuisen Domes

NASA has changed the target landing site for Astrobotic’s first Moon lander—launching this year as part of the agency’s CLPS program—from the northeastern lunar lava plain of Lacus Mortis to an unspecified lava plain just outside the Gruithuisen volcanic dome pair in the northwest.

NASA says in the announcement that this relocation would increase the scientific return from the 11 agency-enabled instruments onboard but doesn’t specify how so, other than stating that the mission science would now complement a future CLPS landing mission to one of the two domes in 2026. Since CLPS is managed by NASA’s Science Mission Directorate, I hope we can learn more about the scientific gains due to this relocation in future communications, especially how it improves upon the previous location’s suitability to study how water gets transported from the Moon’s equator to permanently shadowed regions on the poles where it can remain preserved for billions of years.

You see, 5 of the 11 NASA-enabled instruments onboard Astrobotic’s lander are supposed to collectively detect various forms of lunar water and other such volatiles, including water ice traces underground as well as gases released by the solar wind striking the lunar soil. Astrobotic’s previous landing site at 45° N presented a good equator-pole transition point for said purpose but its unclear how the regions in and around Gruithuisen domes lying roughly at 36° N are apt. While, yes, the silicic nature of the two domes may make them relatively water-rich, it’s not clear if and how well that translates to the unspecified nearby lava plain.

Relatedly, NASA also relocated the landing site of Intuitive Machines’ first CLPS lander last year, from near the equator to the Moon’s south pole. Along the same line of thought, the absence of volatile-measuring NASA-funded instruments onboard the lander is even more puzzling based on publicly available information. We hope to see a formal post from NASA on the rationale behind this relocation as well. NASA’s newly launched CLPS Blog is going to be intriguing to follow to such ends.

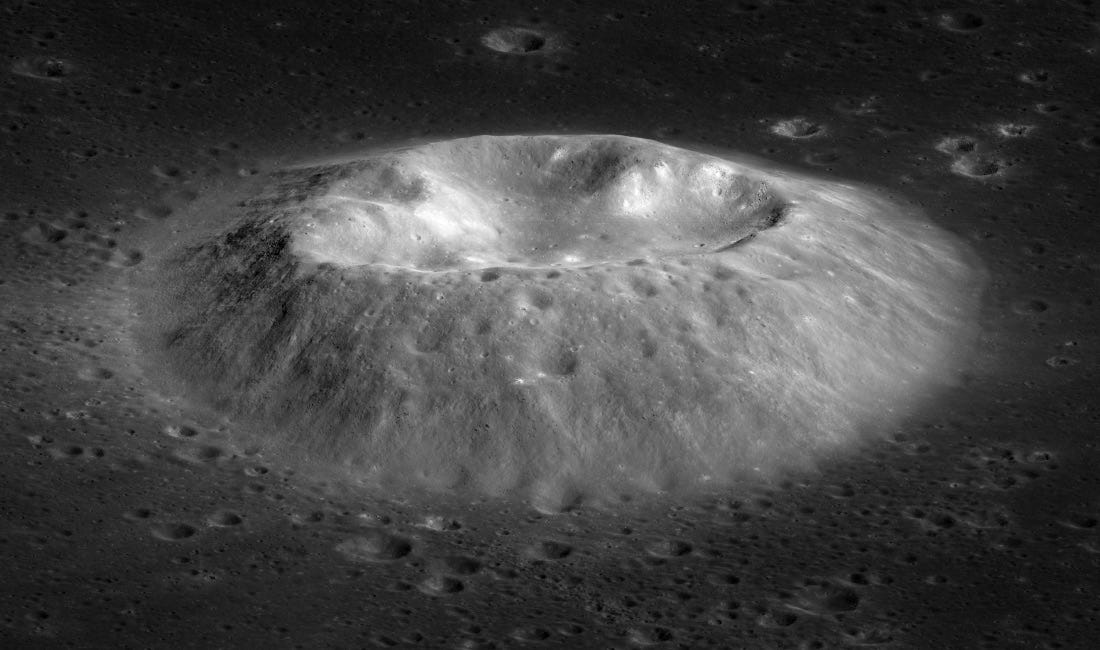

In any case, the to-be-selected NASA-funded CLPS lander descending on the summit of one of the Gruithuisen Domes in 2026 will be something to look forward to. The mission’s lander & rover instrument suite called Lunar-VISE, selected as part of an enhanced science phase for CLPS, will measure the composition of the domes and its thicker, silica-rich ancient lava flows, letting scientists compare them to the thin basaltic flows most common on our Moon. This will greatly expand our knowledge of the Moon’s volcanic past. On Earth, such formations need significant water content and plate tectonics to form but with the Moon lacking both, lunar scientists have been wondering how these features formed and evolved.

Tangent: Eric Berger reports that with the pending installation of the engines on Astrobotic’s first CLPS lander, and much work ahead for the mission’s launch provider ULA to ready the Vulcan rocket, the launch may not happen before May.

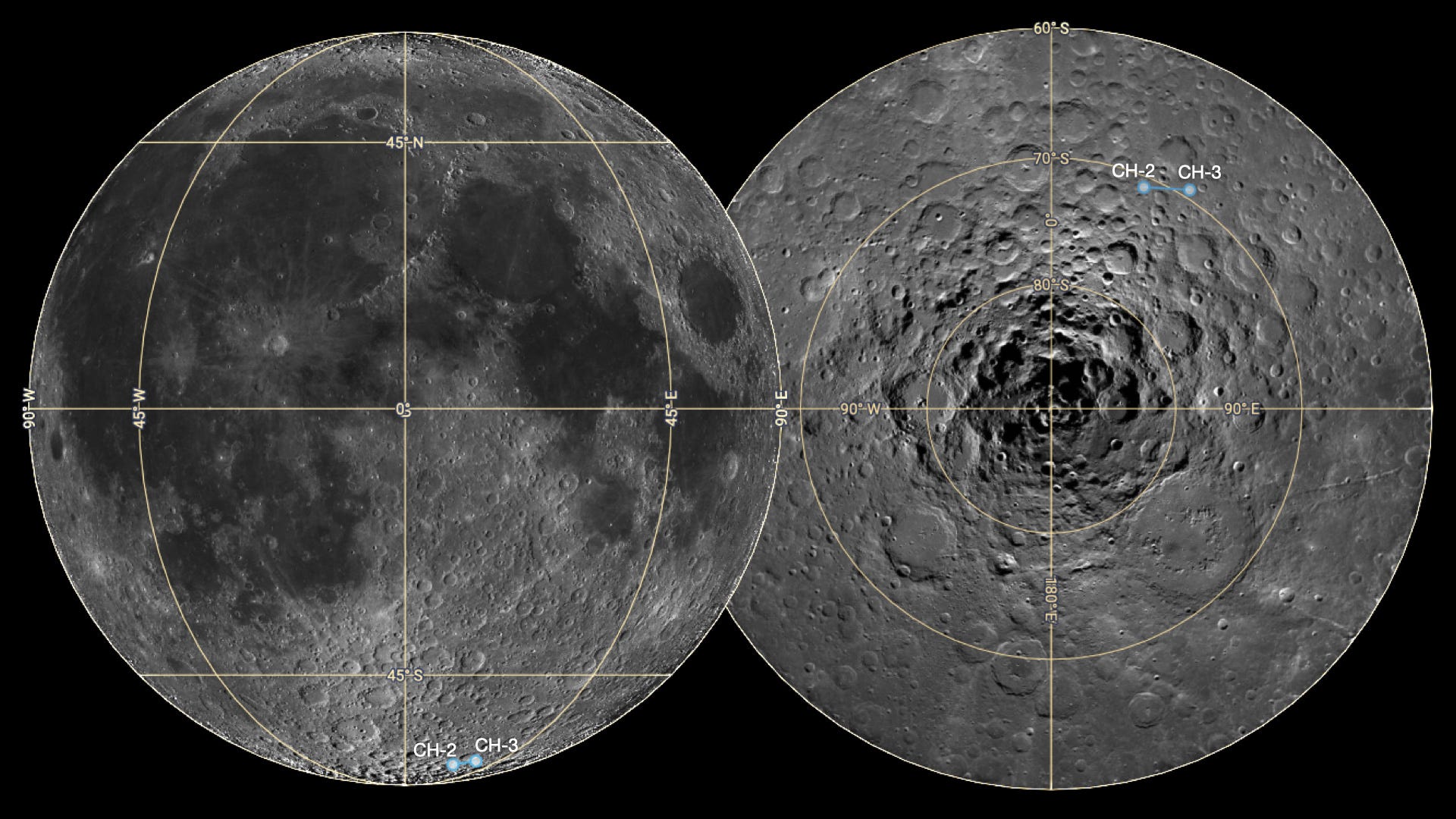

Chandrayaan 3’s crusty landing site

ISRO, unannounced, finally updated its official webpage on the Chandrayaan 3 Moon landing mission with new details, including a host of lander specifications such as the onboard sensors, the engine configuration, and the targeted touchdown velocity. The page’s mention of the landing site is particularly interesting. Launching later this year, the Chandrayaan 3 lander will attempt a lunar touchdown at the near-polar location of 69.37 S, 32.35 E (click the link to browse on an interactive map). That’s roughly just 100 kilometers east of the Chandrayaan 2 landing site (70.83 S, 22.67 E) lying in the same larger rocky highland region, which makes sense given the identical goals of the landing part of the two missions.

Like other lunar highlands, the Chandrayaan 3 landing region is expected to contain material from the ancient lunar crust as well as materials ejected when nearby craters formed during the period of heavy bombardment by asteroids and comets roughly 3.8 to 4.1 billion years ago. Both of these types of materials are great targets for the two spectrometers onboard Chandrayaan 3’s rover, which will explore the landed region for one lunar day i.e. 14 Earth days.

Many thanks to Epsilon3 for sponsoring this week’s Moon Monday.

ESA is “turning astronauts into Moon explorers”

ESA’s Pangaea campaign to coach future lunar astronauts in geology—a highly valuable skill when exploring our Moon and collecting samples—has trained 10 astronauts from 3 space agencies over 5 expeditions since 2016. Now that the program has matured, its director Francesco Sauro and his colleagues have published a paper describing how they designed the efficient and modern lunar field training course as a way to prepare astronauts for future mission-specific training the likes of Artemis. They hope that Pangaea will serve as a useful astronaut training model for other space agencies and also promote international cooperation.

The last Pangaea batch saw European astronaut Andreas Mogensen, European engineer Robin Eccleston and NASA astronaut Kathleen Rubins explore various strikingly Moon-like geological sites across Europe: the Italian Dolomite mountains, the Ries impact crater in Germany, the Spanish volcanic island of Lanzarote, and the Norwegian fjords of Lofoten. In September 2022, ESA began training the next batch of two astronauts—ESA’s Alexander Gerst and NASA’s Stephanie Wilson.

More Moon

- As part of a new U.S.-India partnership to collaboratively build some “Critical and Emerging Technologies”, the two nations announced on January 31 that one such upcoming initiative will identify possible contributions from ISRO and Indian aerospace companies to NASA’s CLPS program, which aims to regularly, commercially send payloads, instruments, and hardware to the Moon on privately built U.S. landers. This is an unexpectedly nice trajectory but I was more surprised by the lacking mention of India’s Chandrayaan 2 lunar orbiter, which represents an untapped opportunity for NASA and ISRO to have the polar orbiter contribute observations and datasets for Artemis planning to fill in gaps left by NASA’s gracefully aging Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Combined, these moves can positively affect India’s undecided stance on the U.S. led Artemis Accords, which aims for globally cooperative lunar exploration.

- On January 16, technicians at NASA’s Kennedy Space Center completed installing the main engine nozzle and heat shield of the Orion spacecraft’s power-and-propulsion-providing European Service Module. This hardware will be used for NASA’s Artemis II mission to send astronauts around the Moon and back.

- The Solar X-ray Monitor (XSM) on India’s Chandrayaan 2 orbiter has a dedicated website where you can see a graph of the instrument-measured high-resolution X-ray spectrum of our Sun and its atmosphere. The plot is autoupdated daily and you can input date ranges to check the Sun’s measured X-ray activity during that period. If that flared your interest, check out my article on how the instrument is uniquely aiding the study of our Sun’s flares.

Jobs and events

The Open Lunar Foundation is hiring an “Innovation Program Coordinator” to lead organization-wide project development and community engagement. The position provides flexibility in time zones, and is remote.

The Lunar and Planetary Laboratory at the University of Arizona is seeking candidates for the position of Researcher/Scientist III, with the job profile including working and collaborating on projects involving lunar sample analyses.

The Royal Society is hosting an in-person & online meeting on February 13–14 titled “Astronomy from the Moon: the next decades” to discuss our Moon’s potential as a platform for astronomical observations and its related policy implications. Attending the event is free.

Relatedly, the Royal Society published a special journal issue in 2020, whose papers explore how deploying various kinds of telescopes on our Moon—from radio to infrared and optical—can improve our understanding of the Universe’s origins at a level beyond the reach of any planned telescopes on Earth or in orbit. I’ve shared Open Access links to said papers in Moon Monday #3.