A worrisome report on safety issues at SpaceX

I’d like to bring your attention to a worrying report on SpaceX’s safety issues as published yesterday by Reuters based on what looks like a comprehensive investigation. The whole article is worth a read but I’m excerpting below some notable parts that either need to be taken seriously or disproved with new information.

Firstly, here’s an overview of what the investigation unfolded to be “at least 600 previously unreported workplace injuries”:

Since LeBlanc’s death in June 2014, which hasn’t been previously reported, Musk’s rocket company has disregarded worker-safety regulations and standard practices at its inherently dangerous rocket and satellite facilities nationwide, with workers paying a heavy price, a Reuters investigation found. Through interviews and government records, the news organization documented at least 600 injuries of SpaceX workers since 2014.

Many were serious or disabling. The records included reports of more than 100 workers suffering cuts or lacerations, 29 with broken bones or dislocations, 17 whose hands or fingers were “crushed,” and nine with head injuries, including one skull fracture, four concussions and one traumatic brain injury. The cases also included five burns, five electrocutions, eight accidents that led to amputations, 12 injuries involving multiple unspecified body parts, and seven workers with eye injuries. Others were relatively minor, including more than 170 reports of strains or sprains.

Now here’s an example of what looks like an avoidable injury incurred by a rushed test of a Starship Raptor engine:

One severe injury in January 2022 resulted from a series of safety failures that illustrate systemic problems at SpaceX, according to eight former SpaceX employees familiar with the accident. In that case, a part flew off during pressure testing of a Raptor V2 rocket engine—fracturing the skull of employee Francisco Cabada and putting him in a coma.

The sources told Reuters that senior managers at the Hawthorne, California site were repeatedly warned about the dangers of rushing the engine’s development, along with inadequate training of staff and testing of components. The part that failed and struck the worker had a flaw that was discovered, but not fixed, before the testing, two of the employees said.

There’s more follow-up about the event in the article, which I recommend reading for more context.

Even generally, it looks like some precautionary measures for safety haven’t been a priority based on this example:

To speed work and cut costs, SpaceX started manufacturing rockets in tents next to an undeveloped Gulf of Mexico beach. Workers welded rocket parts up to 12 hours a day, six days a week, often in temperatures over 100 degrees Fahrenheit, the SpaceX workers said. When overcome by heat, they were given IV fluids and sent back to work.

When high winds disrupted the work, supervisors shut the tents, closing off ventilation that is essential for safe welding, according to the six current and former workers. OSHA warns that welding stainless steel can generate a highly toxic, cancer-causing dust. The agency told Reuters it requires companies to assess the danger of such environments through air sampling and to implement a “respiratory protection program” when needed. One former welder, Phillip Fruge, said he asked managers for respirators commonly used to protect welders’ lungs, but they weren’t provided.

“We could see the clouds of the dust filling the tent,” Fruge recalled. “Everyone was just breathing it in, day after day.”

More than the anecdotes though, it’s the numbers quoted below of SpaceX facilities having a higher than expected injury rate in the industry which warrant serious consideration of systemic issues and willful negligence:

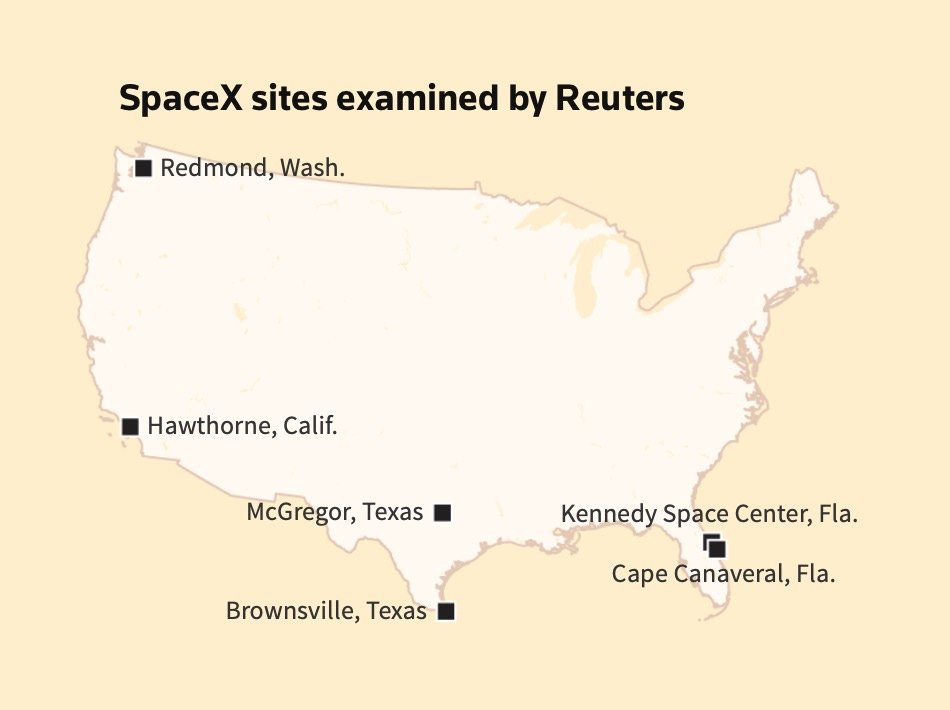

The 2022 injury rate at the company’s manufacturing-and-launch facility near Brownsville, Texas, was 4.8 injuries or illnesses per 100 workers—six times higher than the space-industry average of 0.8. Its rocket-testing facility in McGregor, Texas, where LeBlanc died, had a rate of 2.7, more than three times the average. The rate at its Hawthorne, California, manufacturing facility was more than double the average at 1.8 injuries per 100 workers. The company’s facility in Redmond, Washington, had a rate of 0.8, the same as the industry average.

This data comes from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. The data source informs us that the rates for space vehicle manufacturing in 2022 when including propulsion unit parts and auxiliary equipments—both of which allow for a more fair comparison—are 1.2 and 1.4 respectively, up from 0.8. The article’s point thus stands nevertheless.

Moreover, the article asserts that SpaceX hasn’t been adequately reporting injuries in the first place, and that it downplays their seriousness:

The more than 600 SpaceX injuries Reuters documented represent only a portion of the total case count, a figure that is not publicly available. OSHA has required companies to report their total number of injuries annually since 2016, but SpaceX facilities failed to submit reports for most of those years. About two-thirds of the injuries Reuters uncovered came in years when SpaceX did not report that annual data, which OSHA collects to help prioritize on-site inspections of potentially dangerous workplaces.

[…]

CalOSHA levied a fine of $18,475 for the violation that resulted in Cabada’s skull fracture. SpaceX unsuccessfully disputed the agency’s classification of the violation as “serious” and appealed the penalty as excessive, asking for a reduction to $475.

In another case, CalOSHA never inspected the company following a serious accident resulting in a leg amputation. But the agency may not have known the accident happened at all: A Reuters review of agency documents indicated it had no record of the 2016 incident.

Federal and state law require companies to immediately report all employee deaths, amputations and injuries resulting in hospital admissions. It isn’t clear whether SpaceX ever reported the injury. Neither the company nor CalOSHA commented on why the agency had no report on it.

Lastly, not that it’s surprising or would be expected, but still:

SpaceX did not respond to questions from Reuters and a detailed description of this article’s findings.

There’s no doubt there must be much more to the story, which only few at SpaceX would actually know. But this investigative report led by Marisa Taylor seems like a wide enough window into the company that we never had before. I’ve been browsing comments to this story across the Web, trying to find people refuting the specific work conditions or injury incidences mentioned, and haven’t found any good counters yet. Since my search is inherently narrow, please share any good follow-ups you find that help get a better understanding of what’s really going on.

Regardless of the specifics and true extent of this problem though, I’d like to point to the aforementioned higher than expected injury rates with a question: When we do not accept loss of a single life in human spaceflight without far-reaching programmatic consequences or outright cancellations, and strive a good deal above that to avoid any severe injuries to astronauts, why should the rate of such harm be any higher for the people making human spaceflight happen?

→ Browse the Blog | About | Donate ♡